Insiders know that the art world is like one of those airline maps with fine lines over-arching the globe. It transcends cartographical, political and social geography more than any other human endeavour except, perhaps, the natural sciences. It is a spontaneous, living bastion against nationalism and xenophobia; for its members, Berlin, Cochin, Gwangju, Dakar, New York and Tbilisi all have merit.

In fact, it seems that last month, Tbilisi was the place to be (after the Venice Biennale, of course). Before the Tbilisi art fair (TAF, 17-19 May) opened, Antonia Carver, ex Dubai art fair, now director of the Jameel Foundation, was in town. Leading Paris dealer Kamel Mennour had a stand and took part enthusiastically in the other events on offer. Kosme de Barañano, the Spanish curator of the Baselitz show currently in the Accademia in Venice, was there, and so was the minister of culture of Bahrain.

The artist Jeff Cowen came with Sebastian Neusser, the director of his gallery, Michael Werner, while the Moscow-based financier, Charlotte Philipps, gave a podium talk on collecting (she likes body parts) with Irena Popiashvili of New York, the founder of the Tbilisi Kunsthalle, the organiser of the talks programme and also the curator of a minimalist sculpture show by the grand-daughter of the last Austro-Hungarian emperor, Gabriela von Habsburg, who turns out to have dual Georgian nationality.

Nic Iljine, who lives in Frankfurt and is advisor to the Guggenheim and Hermitage museums, is a member of the fair’s board. Eric Schlosser, its artistic director, is French, but based in Moscow. Théo-Mario Coppola came from Naples, where he is the curator of the Taurisano collection, to be the curator of Hotel Europa, an excellent, international exhibition in parallel with the art fair ranging from the Russian collective Chto Delat to the London-based Swiss Uriel Orlow to the French Yasmina Benabderrahmane. This was just one of the collateral events engendered by TAF although only in its second year.

The fair itself was quite small, with some 30 galleries from Georgia, France, Switzerland, the US, Bulgaria, Germany, Lithuania, Spain, Belgium, Azerbaijan, Austria and Portugal. The Russians were notable for their absence after having been present in force at the first fair; Georgia has a love-hate relationship with its huge neighbour, currently tending towards the second due to encroachments on its own territory.

That being said, the most eye-catching stand was Ria Keburia gallery, with the Russian performance artist Sasha Frolova, the winner of the 2014 Alternative Miss World contest, who wore a bondage mask and huge latex curlicues. This gallery also has a foundation to support young Georgian artists.

The winner of the 2014 Alternative Miss World contest, Sasha Frolova, on the stand of the Georgian Ria Keburia gallery © The Art Newspaper

Otherwise, it was a fair of mostly domestic-sized works, very few costing more than €10,000 and many at under €3000. It is an enticing event for buyers who want to buy for the pleasure of it rather than make a hard-nosed investment.

It was interesting to see works from the communist years, specifically because they come out of a different art ecology, but there were not many. A monochrome female figure in profile by Ana Shalikashvili (1919-2004), who spent her life doing cartoon movies, caught my eye for its yearning attitude. Another artist who stood out for his idiosyncrasy was Merab Abramishvili (1957-2006), who painted delicate fruiting plants in faded colours in tempera on stucco, inspired by the wall paintings in Georgian churches. Although unheard-of in the West, he must have a following at home because they were priced at over €100,000.

It would be good if the fair made more space for works from before independence in 1991, when a great deal of art was produced but there was almost no art market. As with the shows of 1930s to 1980s Middle Eastern art attached to Art Dubai, this could build the bridge between contemporary art, which is still considered a minority interest in Georgia, and the art that preceded it, from the other side of the ideological curtain. If done with the art historians who know this period, it would be a great service to Georgian history of art and to collectors, while the fair need not fear seeming kitschy and provincial; the western art world is much more heterodox today and can allow itself to enjoy academic and even regime art if it is of good quality.

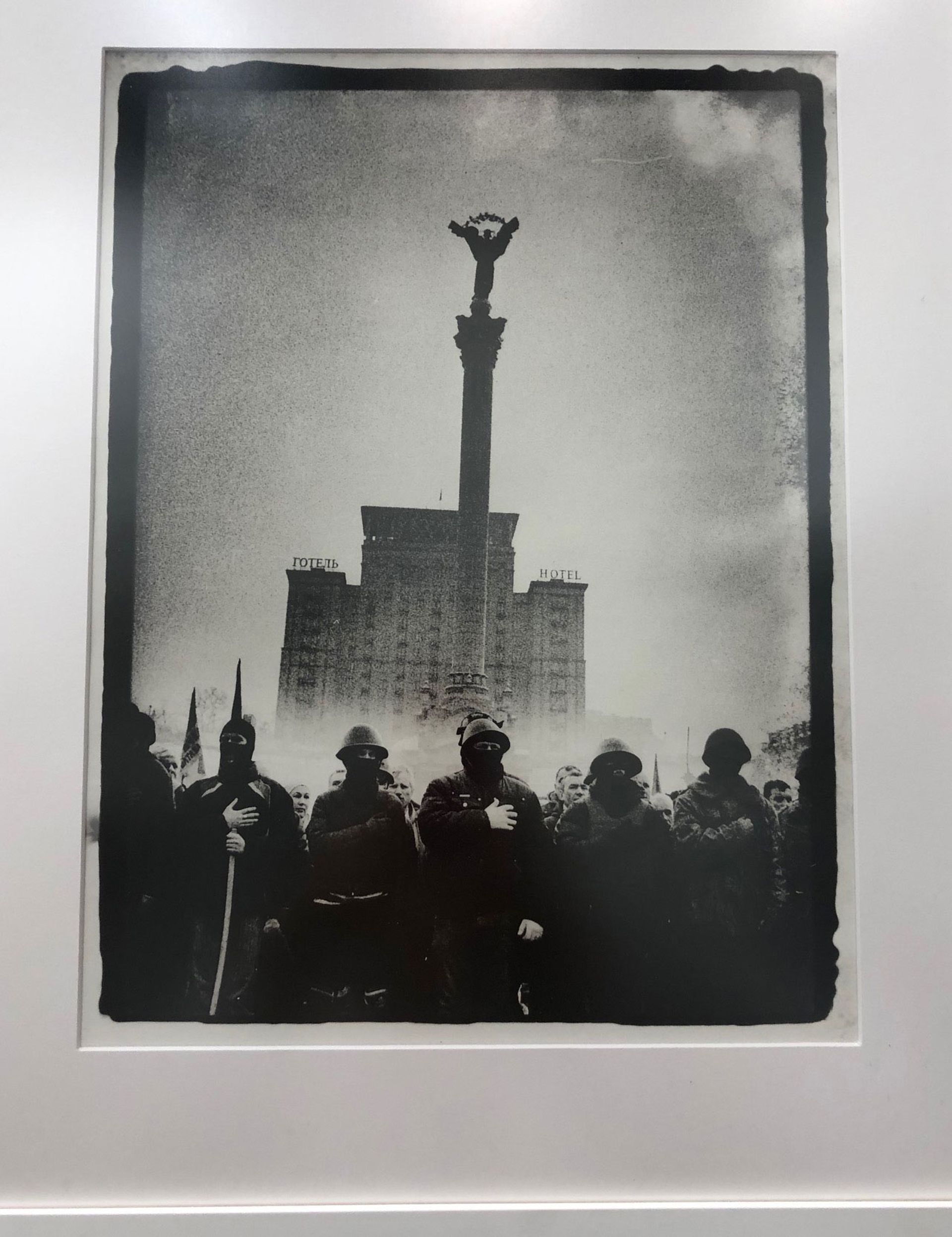

The desire to connect with past history was visible in many works. Kamel Mennour brought a series with a story behind it, the ledger book from a cultural centre created in a Kosovar village called Runik when Yugoslavia was at peace under Tito, only to be destroyed in the Balkan wars. It was found by Petrit Halilaj among the rubble, who has added pen and ink grotesques to the faded invoices. A photography exhibition from PhotoKyiv called Palette of Pain documented the last decades of the USSR, from 1970 to the present day, with dramatic photo-reportage by Sergey Lebedynsky of the Maidan protests in Kyiv in 2014.

Maidan protest, 2014, by the Ukrainian Sergiy Lebedynskyy on the stand of PhotoKyiv, priced at €1000 © The Art Newspaper

In a section of the fair called Discourses, there was a mesmerising video of a man reading a very, very long poem with great emphasis and complacency in a hall with pathetically tattered curtains. The “zam-zams", “tsst-tssts”, “gr-grs” revealed even to a non-Georgian speaker that it was a piece of avant-garde creativity. What was remarkable was the unfading attention of the audience, which was made up of an association for the blind. Showing it as an art work seemed to be both nostalgic—a tribute to the belief in elite culture for all—and critical, because the poet was the regime architect Shota Bostanashvili, who therefore had the clout to impose such a self-indulgent marathon on his audience. The gallery was Nectar from Georgia.

Georgia’s rich but autocratic and Muslim neighbour, Azerbaijan, was present with a single gallery and an exhibition of sophisticated and at times moving videos on gender issues, curated by the dramatic video artist Sabina Shikhlinskaya, who pointed out that Azerbaijan confounds prejudices; its women got the vote in 1919 ahead of all the European countries.

The Hive, a group show with works chosen by an impressive international jury, suffered from the “camel is horse designed by a committee” syndrome and would be better served by a single curator next year. One work had real personality, a large paper collage by Tamar Nadiradze and the curator Nini Darchia called Ode to Spring (2019), like a mille-fleur tapestry but full of young people setting fire to the flowers and trees.

Ode to Spring, a large paper collage of 2019 by the Georgian Tamar Nadiradze and the curator Nini Darchia, in the young artists section, Hive © The Art Newspaper

For a more interesting sample of home-grown conceptual artists, the place to go was the show called Oxygen on the unfinished floors above the funky Stamba hotel, which financed it, yet another example of how TAF has managed to galvanise the whole town, with artists and collectors opening up their homes.

One of these belonged to Vakhtang Kokhiashvili (1930-2010), a poignant case because he made monumental stained glass under the communists and, to judge by the photos, it was very good, but after independence an official decision was taken to destroy this public art. At the same time, however, he was quietly making Pop assemblages for his own satisfaction and these survive in his studio. To us visitors who raced from place to place, there was the feeling that there was a great deal more to be discovered and discussed, but the whole experience was delightful and stimulating.

Where should the fair go from here? Popiashvili believes it should link up more with art institutions, such as the Free University of which she is dean, and also involve design, theatre design (the theatre design school run by the scenographer Giorgi Meskhishvili is particularly good, she says) and even fashion, in which Georgians are making their mark (the chief designer for Balenciaga is a Georgian).

The multi-media video artist Uta Bekaia, who lives in New York but came back after 20 years “to find his roots”, had a dramatic, room-filling video work of himself as multiple characters at ERTI gallery. He said, “I feel that Tibilisi is vibrant and in the making; it is very open, an empty canvas. Creating art can provide a sense of identity. I see that young artists here are becoming more original, and in the last four years, lots more art spaces have opened up.” He emphasised the importance of having galleries to support and encourage the artists.

New York artist Uta Bekaia with nostalgia for his native Georgia © The Art Newspaper

Tamuna Arshba, the director of ERTI, which was founded in 2015 and is backed by Natia Khuntua, said: “I would love to see corporations support the fair. We did our first collaboration with the Bank of Georgia, which buys one work from each of our shows; they should get involved in the fair too. A competition, with an international jury to guarantee impartiality, would also help publicise it.”

Certainly, financing TAF is a key issue. The costs are currently being born by its founder Kaha Gvelesiani and his co-investors in ExpoGeorgia, with just one bank, TBC, contributing. The money from the government was halved part of the way through and then reduced yet again just as the fair was about to open. “This is chaotic and discouraging”, Gvelesiani says. “We have managed to bring a major cultural event to Georgia, with all that this means also in terms of tourism and prestige. We need commitment to be able to grow it to its full potential, which you can already see from what we have achieved.”

• The author is a member of the advisory board of TAF, the Tbilisi Art Fair

CORRECTION: ERTI gallery is not owned by Lyonid Fridlyand as stated, but by his wife, Natia Khuntua, and has been duly amended.