An artist residency programme in Chicago is putting the city’s notoriously severe legal system under aesthetic scrutiny. As part of the Courtroom Artist Residency, artists may sit among the friends and family members of defendants waiting to be tried at Cook County’s Criminal Court and witness the brisk flow of 100,000 people processed there annually. The programme is unaffiliated with the court system, however, which may not be aware of its existence. “Artists’ opinions are not normally sought or included in courts,” says Marc Fischer, the residency’s organiser and the founder of the artist project Public Collectors.

Fischer invites one artist at a time to sit with him all day in court, watching, taking notes and drawing. “The project frames the artist as an active observer and participant in a democratic society.” Public attendance at criminal trials is a constitutional freedom of US citizenship, just as it is in the UK, Belgium and several other countries.

After each court session, Fischer publishes a pamphlet that includes the artist’s response, and these are collected in short books published by Public Collectors. A common theme among them is the theatrical setting of the courtroom and its central actor, the judge. In one surreal interaction, Fischer observed a judge patronisingly reward sober drug offenders with lollipops from a fishbowl. In another, the judge decorated his courtroom with abstract black-and-white prints and colour photography of an “ominous” landscape, recalls Claire Pentecost, one of the resident artists.

Police brutality is a dominant narrative of the trials the artists attend. Victims with shattered bones and head injuries detail their gory run-ins with Chicago’s police force. One man, Gerald Reed, was imprisoned for 28 years after police allegedly beat a confession from him. Fischer and a couple of the residency’s artists were in attendance to see wheelchair-bound Reed’s conviction overturned.

“Being there creates a depth of experience that’s impossible to get from reading anything—even a transcript, or watching a video,” says the resident artist Josh Rios. After his time in the courtroom, Rios published When the Dead Speak Through the Living, a text about the victim impact statement he observed.

In public art, witnessing usually comes in the form of a large bronze monument, but Fischer’s project is a real-time act of testimony. Some cases, and fates, are decided in under two minutes, Fischer says, and he has seen the system inordinately punish poor men of colour. Without courtroom spectators, small injustices and daily racism can fade into normalcy, he adds. “Artists can deal with the emotional space of the court, or details that might elude journalists and activists,” Fischer says. “Here, you are confronted with the horrors of injustice. Artists can help demystify that.”

Not a mere conceptual exercise, Fischer’s project has ripple effects for the judges themselves who, in Chicago, retain their seats by public vote. The more people hear about their activities, the more likely they are to vote accordingly.

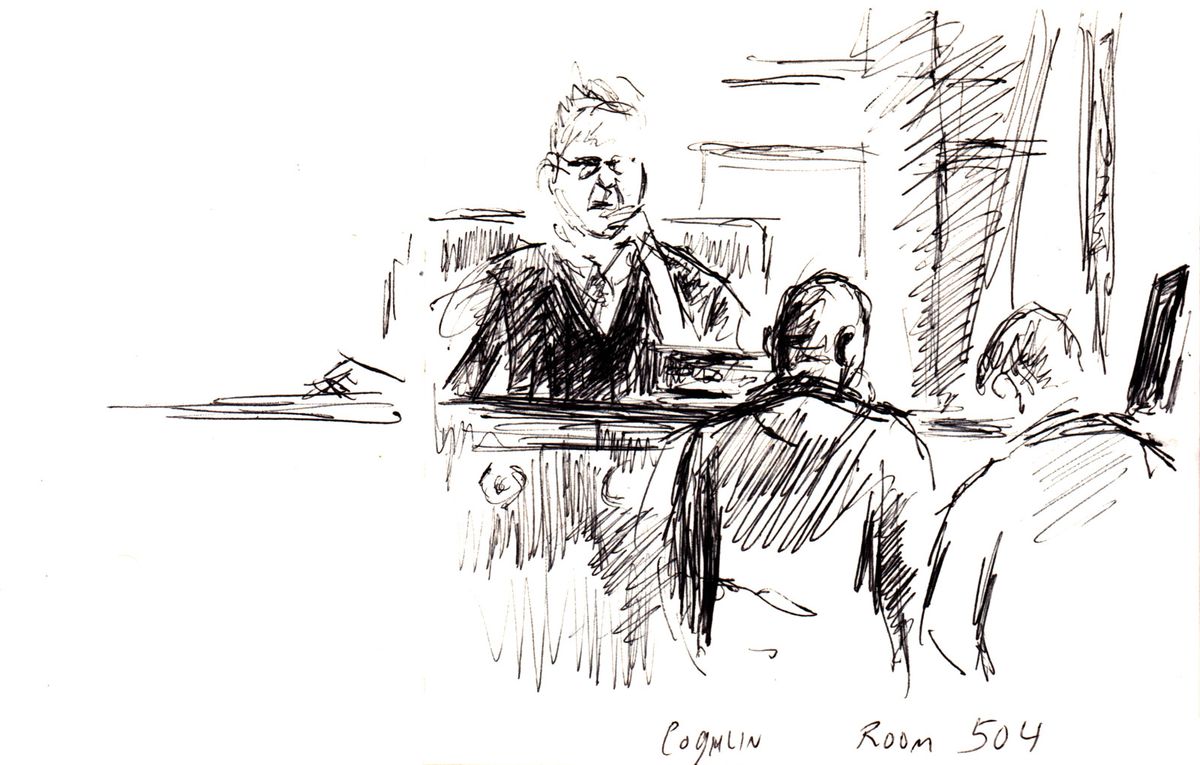

Last November, for the first time in 28 years, the Chicago Circuit Judge Matthew Coghlan, who had been accused of mistreating racial and ethnic minorities, was voted out.