At least 90% of the Native American art in all museum collections was made by women, according to Jill Ahlberg Yohe, the associate curator of Native American art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. But that fact, as well as recognition of the individual artists, has been missing from institutional narratives, which typically present Native works as representative of entire cultures.

“We now have the opportunity to showcase the ‘un-anonymous’,” says Yohe, who, with Teri Greeves, an independent curator and member of the Kiowa Nation, has organised the exhibition Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, opening on 2 June at the Minneapolis museum. With more than 115 works of pottery, textiles, beadwork, painting, sculpture, photography, installation, drawings, prints and couture spanning 1,000 years, the show identifies around 70% of the makers—an effort informed by a 21-person advisory panel including Native American artists and scholars.

One previously unknown, largely self-taught artist is Mary Sully (1896-1963), a Dakota Sioux woman who drew explicit connections between Native American art, abstraction and Art Nouveau-type designs in triptychs made with coloured pencil on construction paper. She is now poised to enter the canon of Native American art, as well as American art as a whole, after the conservation of three triptychs to be exhibited for the first time since her death—and probably ever.

Portrait of Mary Sully © Collection of Philip J. Deloria

“To have them in an art museum context, we are treating them with the care we would treat a Matisse work,” Yohe says. She guided the conservation process with Dianna Clise, the senior paper conservator at the Midwest Art Conservation Center, and Philip Deloria, the artist’s great-nephew and a professor of history at Harvard. He has inherited Sully’s entire body of 134 triptychs and published the monograph Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract (University of Washington Press, 2019).

A descendant of George Washington’s portraitist Thomas Sully, Mary lived with her sister, Ella Cara Deloria, a Native American anthropologist affiliated with Columbia University. The sisters travelled extensively from the 1920s to 1940s, when Sully was exposed both to Native art in South Dakota and Arizona through her sister’s ethnographic work, and to the New York avant-garde.

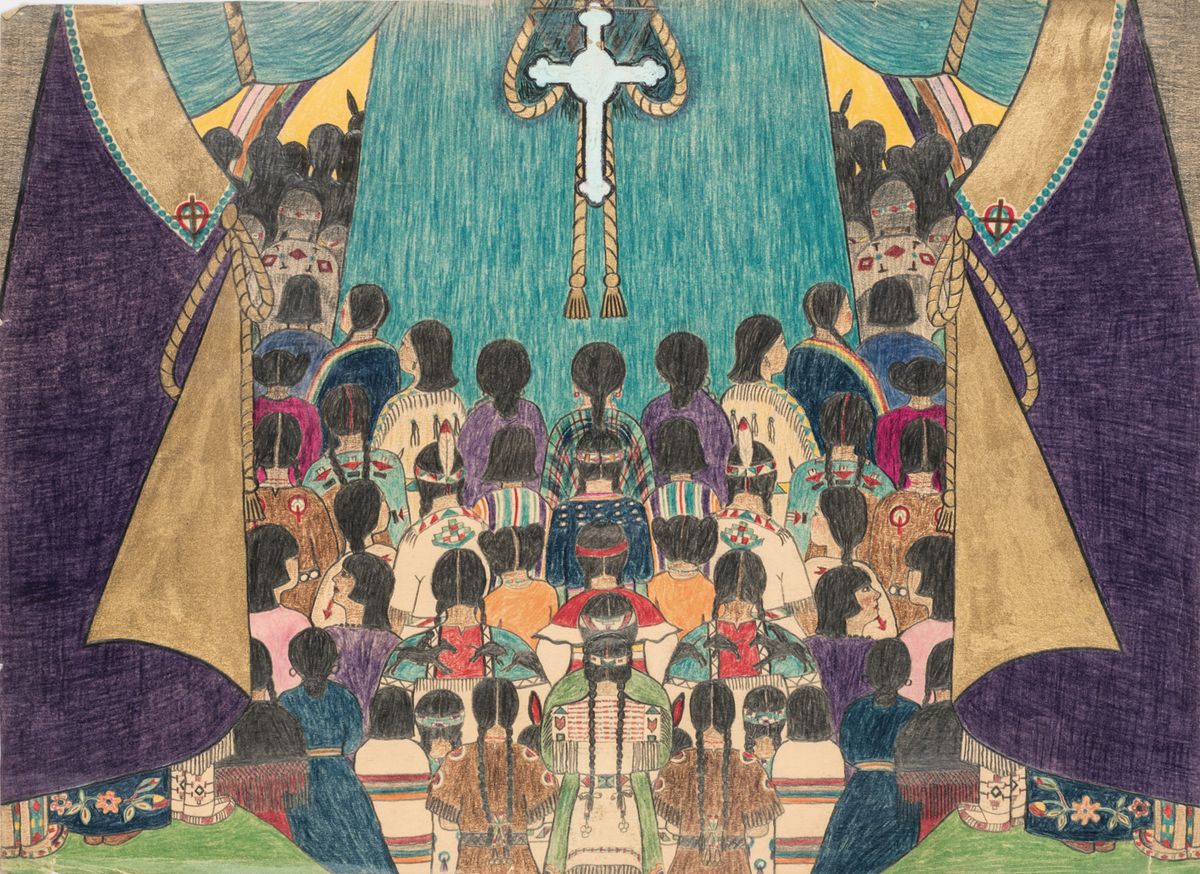

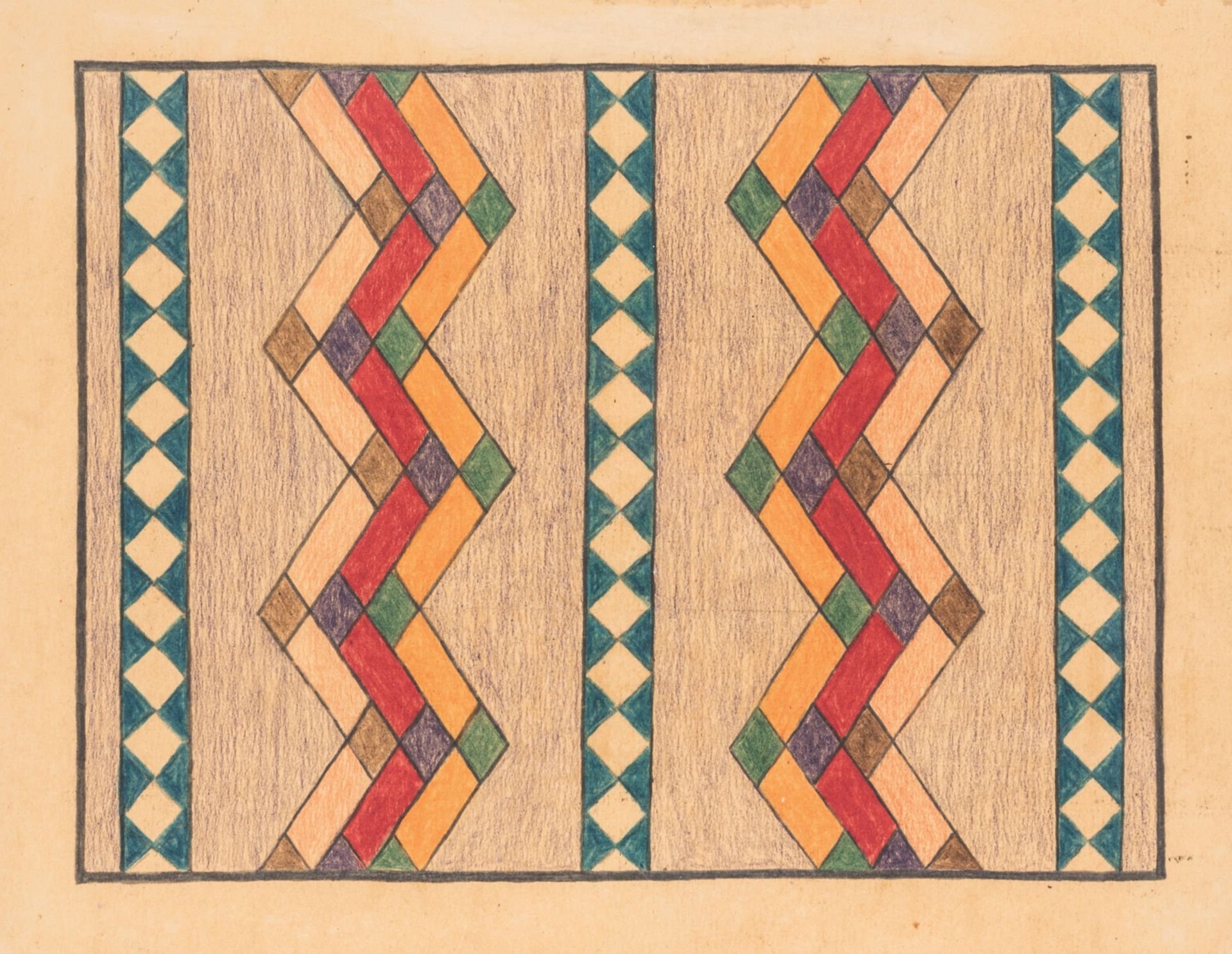

“She’s drawing upon things she’s seeing in the art world and incorporating them into her understanding of Native aesthetic systems,” Yohe says. Sully’s The Indian Church (around 1938-45) comprises three drawings that were simply taped to one another on the back so they could hang vertically from drawing pins. The top panel shows meticulously drawn Native American women in colourful regalia crowded inside a teepee and facing a looming figure with a cross; the middle panel distills details from their clothing into a mesmerising Modernist pattern evocative of Art Nouveau wallpaper; and the bottom panel takes some of the same colours and turns them into a Native American quillwork pattern.

Bottom of Sully's The Indian Church (c. 1938-45) © Collection of Philip J. Deloria

Long folded in a box in the Deloria family home, The Indian Church and the two other triptychs arrived in Minneapolis in an unstable condition. “The panels were no longer securely attached to each other,” Clise says. The question was: “Is the tape part of the artist’s intent, or should it come off because it was clearly having negative effects on the paper?” Deloria says. They decided to remove the tape, which Clise did with a viscous methyl cellulose poultice that delivered controlled moisture to the tape. She then mended tears, filled losses using a compatible paper and in-painted damage on the front to restore visual continuity.

The panels are now mounted to a backing mat and will be stored in frames to protect them. “I’m hoping this is not the last opportunity for folks to see them,” Deloria says.

“Sully was breaking barriers and defying the expectations imposed on so many Native artists to this day,” Yohe says. “This is transformative for future Native art studies.”

• Hearts of Our People: Native American Women Artists, Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2 June–18 August