An exhibition on Gauguin portraits is to include still lifes of sunflowers painted as a tribute to Van Gogh. The show opens today at Ottawa’s National Gallery of Canada (until 8 September) and then moves to the National Gallery in London (7 October-20 January 2020).

Surprisingly, the show will be the first ever to focus on Gauguin’s portraits. With around 50 Gauguins, it will include paintings, drawings and sculptures, covering his entire career. This week, I am focussing on just one aspect of the exhibition: Gauguin’s symbolic “portraits” of Van Gogh, featuring the Dutchman’s famed sunflowers. (Gauguin’s only actual portrait, portraying Van Gogh painting sunflowers, is very fragile and cannot leave the Van Gogh Museum.)

Van Gogh painted his original set of four sunflower still lifes to decorate Gauguin’s bedroom in the Yellow House in Arles, just before his friend’s arrival. Their collaboration was then brought to an abrupt end by the ear incident two days before Christmas 1888. Thirteen years later, in Tahiti, Gauguin completed his own set of four sunflower still lifes, presenting the blooms in various Oceanic settings.

Cornelia Homburg, the exhibition’s co-curator (along with Chris Riopelle), describes Gauguin’s sunflower pictures as “surrogate or commemorative portraits” - since they effectively symbolise the Dutch artist. The Ottawa and London galleries originally hoped to reassemble all four of Gauguin's still lifes, but some loans proved problematic.

One of the still lifes will be shown in Ottawa, coming from a private collection in Milan. This will be joined in London by another, from the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

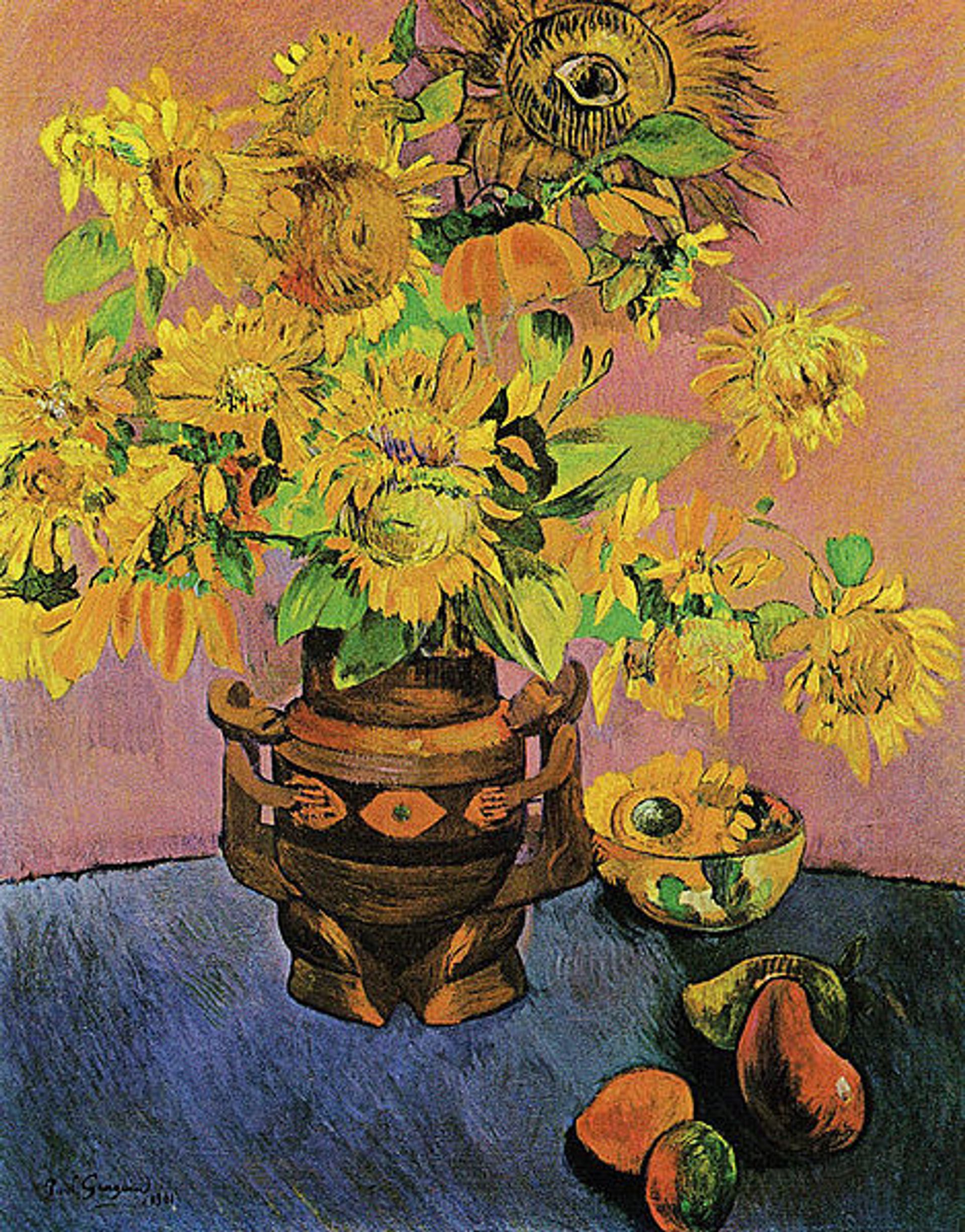

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with “Hope” (1901) Private collection, Milan

The Milan still life tellingly features two images pinned to the wall behind the flowers. The upper one is a reproduction of a nude holding a sprig of flowers, symbolising spring. This is Hope (1872), painted by Puvis de Chavannes, a work which was greatly admired by both Gauguin and Van Gogh - and much discussed while they lived together in the Yellow House. Beneath Hope is an Edgar Degas etching of a Parisian brothel scene (1879-80), with a woman bending over to wash. Gauguin may well have had the print with him when he was staying with Van Gogh.

Paul Gauguin, Sunflowers on an Armchair (1901) Image from www.hermitagemusum.org, courtesy of the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Sunflowers on an Armchair, from Saint Petersburg, is an even more direct homage to Van Gogh. It alludes to Van Gogh’s pair of paintings of the two artists’ empty chairs in the Yellow House. The face of a Tahitian woman appears in a corner of the composition. Gauguin has left it ambiguous whether it is a portrait hanging on the wall or a figure walking past a window.

Paul Gauguin, Sunflowers on an Armchair (1901) © Emil Bührle Collection, Zurich

There are two other still lifes which were not available for the Ottawa and London exhibitions, but they too refer to Van Gogh. One, also entitled Sunflowers on an Armchair, is a variant of the Saint Petersburg composition, but with a Tahitian seascape in the background. It is part the Emil Bührle collection in Zurich and is currently on loan with Bührle pictures at the Musée Maillol in Paris (until 21 July). Gauguin’s fourth still life, Sunflowers with Mangoes, is in a private collection and could not be borrowed.

Paul Gauguin, Sunflowers with Mangoes (1901), private collection © Wikicommons

The four sunflower paintings represent a homage to Van Gogh, but Gauguin’s attitude towards his Dutch friend was ambivalent. Gauguin refused to accept any blame for Van Gogh’s self-mutilation, and he always argued that it was he who had inspired the development of the Dutchman’s art, rather than the reverse. But a decade after their collaboration in the Yellow House, Van Gogh’s fame was beginning to rise, so the ambitious Gauguin wanted to be seen as associated with him.

An intriguing question is how Gauguin could find sunflowers to paint on his Pacific island? In October 1898, exactly a decade after his arrival in Arles, he sent a letter to his Parisian artist friend Daniel de Monfreid requesting “some bulbs and flower seeds: ordinary dahlias, nasturtiums, various sunflowers.... I would like to decorate my garden and, as you know, I love flowers”.

The following year his French dealer, Ambroise Vollard, wrote that “if you care to do some flower paintings... I am willing to buy everything you do”. In 1901 Gauguin obliged, with the four sunflower still lifes.

These were among the last works which Gauguin painted in Tahiti, before moving to the remote Marquesas Islands. In April 1903 he wrote once again to Vollard, complaining that he had waited more than eight months for the promised supplies of canvas, paper and seeds. The seeds were due to come from Vilmorin, a company founded in 1743 and which still remains in business. (Its customers in Gauguin’s time also included Claude Monet and Gustave Caillebotte.)

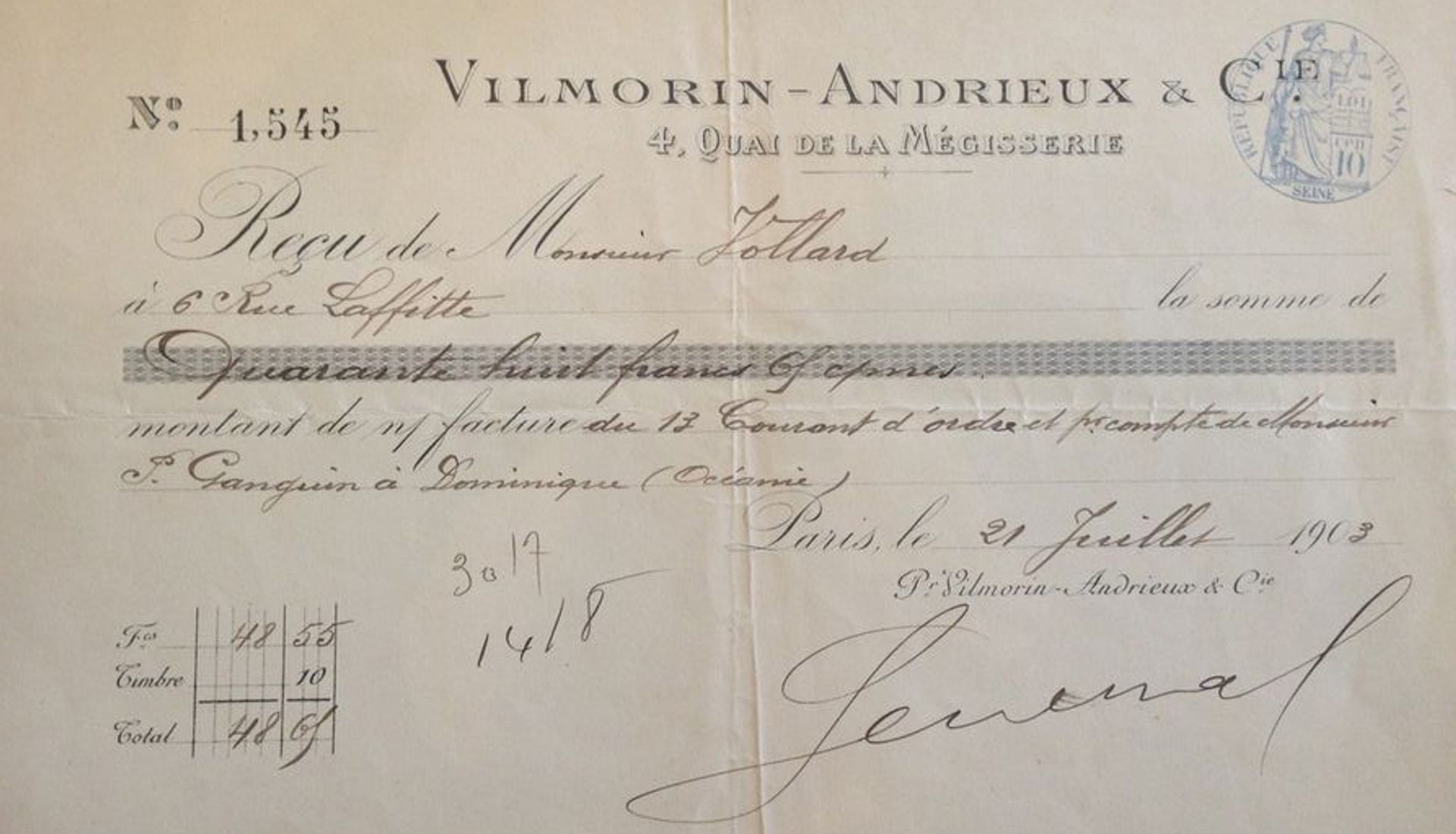

A few years ago I discovered what happened to Gauguin’s seeds. Vollard eventually ordered them, but failed to make the necessary payment. On 1 July 1903 Vilmorin asked Vollard “to pay for the articles ordered by Mr Paul Gauguin, so that, if you reply in the affirmative, we may ship them without further delay.” A Vilmorin receipt records that Vollard finally paid 48.65 francs on 13 July for “Monsieur P. Gauguin à Dominique (Océanie)” (Dominique was then the French name for the island of Hiva Oa in the Marquesas).

Vilmorin receipt for Gauguin’s seeds, 13 July 1903 © Heritage Auctions, Dallas

I found the receipt in an unlikely place: the archives of Auguste Renoir, which were sold by Dallas-based Heritage Auctions in 2013. It remains a mystery why Renoir had the receipt for Gauguin’s seeds, but he was a good friend of Vollard, and somehow the document ended up among his papers.

Sadly, Vollard’s payment came too late. Gauguin had died on 8 May 1903 in his hut on Hiva Oa, at the age of 54. He probably had syphilis and may have suffered an overdose of morphine and a heart attack. Mail from the island took several months to reach France - so Vollard had not heard the news when he finally paid the Vilmorin bill. The seeds were duly dispatched to Hiva Oa, but never reached their recipient.

• Further details of the Ottawa and London exhibitions of Gauguin Portraits are available on the galleries’ websites.

• My book The Sunflowers are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece was published in paperback in February.