Should a modern democracy preserve an architecture and landscape designed to glorify the 20th century’s most infamous dictator? And, if the answer is yes, how?

The city of Nuremberg has grappled with these questions for years. It is now about to embark on an €85m plan to conserve the vast Nazi party rally grounds designed by Adolf Hitler’s architect Albert Speer. The complex, including the 140,000 sq. m Zeppelin Field and the huge Zeppelin Grandstand, is the best surviving testimony in stone to Hitler’s megalomania.

Unlike other Nazi edifices such as the Haus der Kunst in Munich, which is now an exhibition hall, or the Olympic Stadium in Berlin, which still serves as a sports arena, the rally complex—designed for enormous crowds, choreographed military parades and torchlit processions—was hard to repurpose in the new, democratic Federal Republic of Germany. Intended to survive the “Thousand-Year Reich”, it is now a decaying endangered historic site.

“We won’t rebuild, we won’t restore, but we will conserve,” says Julia Lehner, Nuremberg’s chief culture official. “We want people to be able to move around freely on the site. It is an important witness to an era—it allows us to see how dictatorial regimes stage-manage themselves. That has educational value today.”

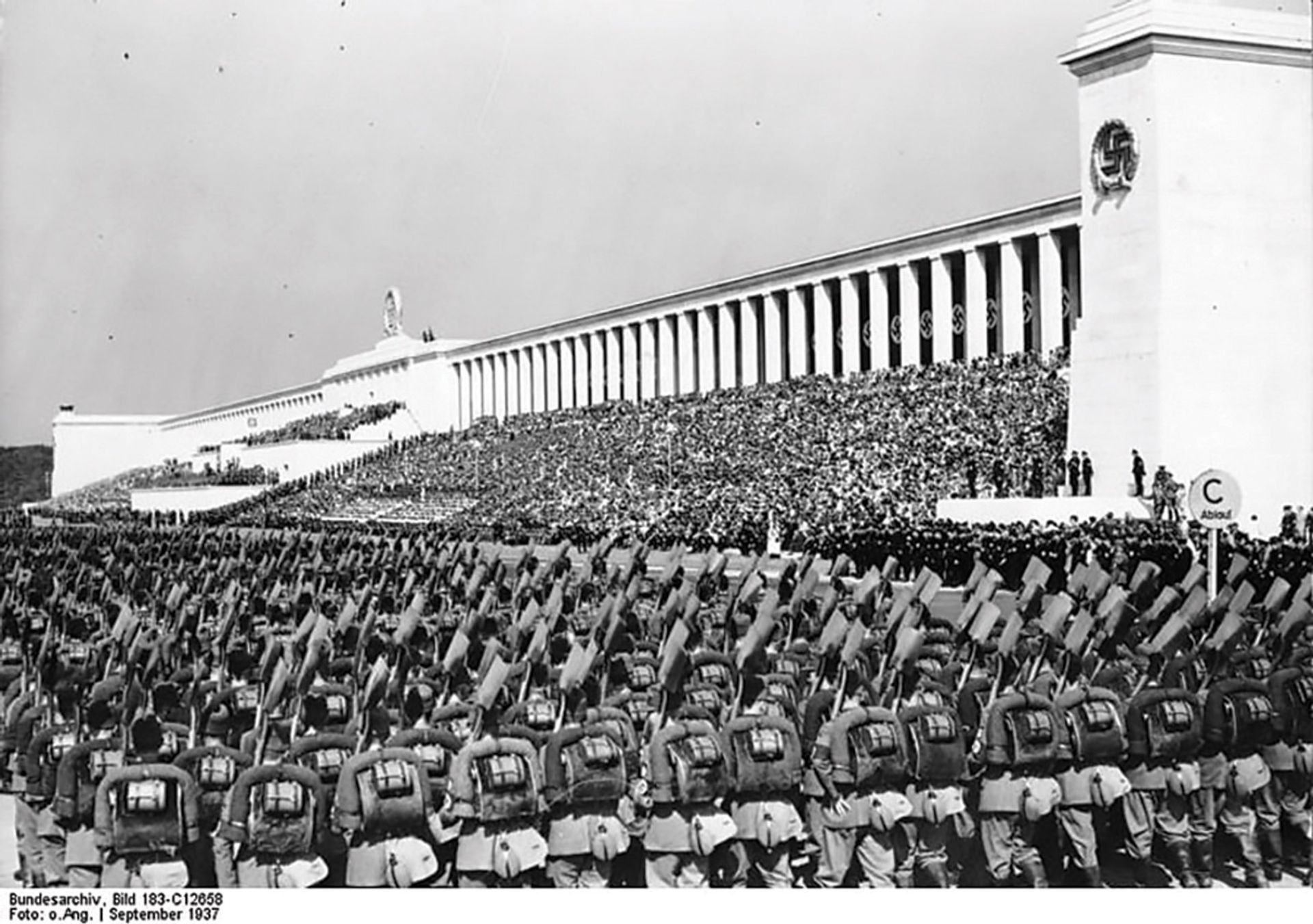

Commissioned by Hitler in 1934, Speer’s construction involved demolishing the Nuremberg zoo and a recently built stadium complex. With a triumphal way for parades, ramparts and towers bearing flagpoles for spectator seating, and a 370m-long colonnaded grandstand comprising a golden hall with gilded ceiling mosaics, swastika reliefs and a rostrum for Hitler’s impassioned diatribes, the site became the central stage for Nazi propaganda.

A 1937 photo from the Zeppelin Grandstand Photo: Bundesarchiv/ O.Ang

The rallies, week-long extravaganzas captured for posterity in Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 documentary Triumph of the Will, took place there from 1933 to 1938. The grounds hosted tanks firing flak at aeroplanes thundering over the field, young men displaying their virility in manoeuvres with tree trunks, and “girls’ dances” to showcase the future mothers of the master race. The 1939 event was cancelled just a few days before the outbreak of the Second World War.

When US troops captured the grounds in 1945, they staged their own parade, culminating in an explosion that destroyed the golden swastika that crowned the grandstand. Part of the site served as a sports field for US troops after the war. In the 1970s and 1980s, Bob Dylan, Tina Turner and the Rolling Stones played rock concerts there.

In 1967, city authorities blew up the grandstand’s double row of pillars because of loose stones, causing severe damage to the rest of the building. Though the entire site has been under a preservation order since 1973, the grandstand was not opened for a survey of the damage until 2007, revealing corrosion, broken stairs, dry rot and mildew.

“The damp is the biggest problem,” says Daniel Ulrich, head of Nuremberg’s construction department. “The original construction was quick and shoddy. It was little more than a stage-set designed purely for effect. The limestone covering the bricks is not frost-proof and water has seeped in.”

The city weighed several options. Reconstructing the architecture would have been viewed as glorifying the Third Reich, and some citizens and historians favoured a “managed decay”. But the city authorities wanted to avoid having to fence off increasingly large parts of the grounds. There were also concerns that the decaying buildings could emit a kind of “ruin romance”.

Others pleaded for the site to be bulldozed. But the authorities did not want to “sweep history under the carpet”, explains Siegfried Zelnhefer, a spokesman for the city. They decided instead to conserve the ruins in their current state and make them fully accessible.

In 2014, the city commissioned a €3m survey to determine the extent of the damage and how much it would cost to make the site structurally safe. The final figure of €85m is to be half-funded by the German federal government. Discussions between the city of Nuremberg and the state of Bavaria on splitting the rest should conclude soon, Lehner says.

Since 2001, a permanent Documentation Centre has served visitors. But the city anticipated around 100,000 visitors a year, and in recent years, 280,000 have come, says its director, Florian Dierl.

The most complex conservation challenge is the damp that has seeped into the stone walls of the ramparts and grandstand, the steps and facades. A ventilation system will be required to remove humidity from the interiors. About a quarter of the stones in the facades and steps are to be replaced by matching concrete blocks. The top layer of the compacted soil stairs of the ramparts will be replaced.

In addition, a new “project room” will be installed in the grandstand. The Documentation Centre will be expanded and information stations erected around the site. The city will still encourage Nurembergers to use the grounds for leisure activities, Dierl says.

“People are welcome to use it for ordinary daily activities because that demystifies the site,” he says. But the city authorities also want to encourage reflection, he adds.

The target date for completion is 2025. Nuremberg is also competing to be a European Capital of Culture that year. “We need a bit of luck to have it all done by then,” Dierl says.