Jörg Immendorff: Ichich, Ichihr, Ichwir, We All Have to Die (Me Me, Me Her, Me Us, We All Have to Die)

Fondazione Querini Stampalia

8 May-24 November

Jörg Immendorff is not as well known as some of his contemporaries in German art, but he is among the most extraordinary artists to have emerged in the shadow of Joseph Beuys, who taught him in Düsseldorf in the 1960s. Like Beuys, a political and social commitment was at the heart of Immendorff’s work: he was a committed communist at one stage, and though he grew disillusioned with the official party, leftist politics dominate his work.

Immendorff has long been admired and widely shown, but the scope of his complex body of work is being explored in depth in 2019 through a survey that began at the Haus der Kunst in Munich and travels later this year to the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, and in Venice, with this show, curated by Francesco Bonamí. “In a time, the late 1960s and 1970s, when painting was seen as a betrayal of the revolution, Immendorff, rather than abandon it, transformed it into a powerful political tool,” Bonamí tells us. “All his career he used painting with indulgence for the medium, but challenging it over and over in a way that maybe only El Greco did in the history of art, breaking the mould of his own time, escaping Mannerism and the traps of beauty.”

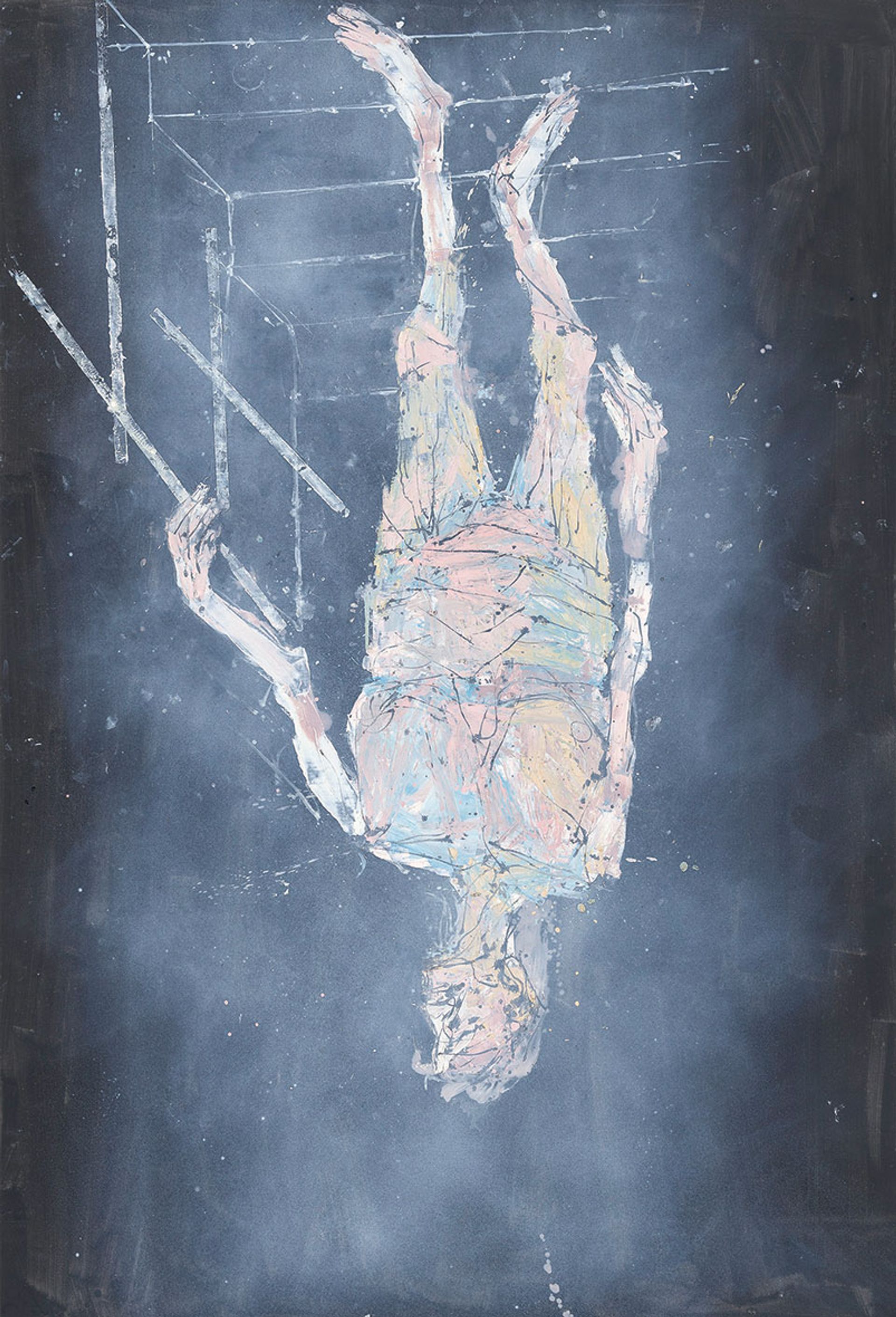

Georg Baselitz, Ankunft (Arrival, 2018) © Georg Baselitz; Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Baselitz-Academy

Gallerie dell’Accademia

8 May-8 September

The curator Kosme de Barañano may have wondered what there was left to say about Georg Baselitz. His exhibition at Gallerie dell’Accademia follows last year’s retrospectives at the Fondation Beyeler and the Kunstmuseum in Basel, and the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, and precedes the Centre Pompidou’s 2020 show. Instead of a sprawling survey, De Barañano chose to trace Baselitz’s 60-year career through a tight narrative lens. “A retrospective is like a symphony,” de Barañano says. “This exhibition is more like chamber music.”

The show—the first time the Venetian museum is hosting an exhibition by a living artist—is thematically arranged around the building’s architecture. The three main rooms, the “trio sonata”, are dedicated to the artist’s portraits, self-portraits and nudes, while the four adjacent smaller rooms—the “string quartet”—feature his drawings.

The works in this exhibition also reveal his relationship to Italy, where he has lived on and off for the past 40 years; he has a home in the city of Imperia. His student sketches after Italian Old Masters are shown alongside drawings he made during a fellowship in Florence in his 20s. Works responding to his beloved Mannerist woodcuts are exhibited in the corridor, and the inverted figures for which he is best known also feature, including in two new, 5m-tall self-portraits, which he painted last summer. “Like Goya”, de Barañano says, he is making some of his best works late in life.

Arshile Gorky, Landscape-Table / Tavolo-Paesaggio (1945) Photo: Philippe Migeat © Centre Pompidou; MNAM-CCI; Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Arshile Gorky: 1904-48

Ca’ Pesaro International Gallery of Modern Art

8 May-22 September

The Armenian-American artist Arshile Gorky seemed to exist between worlds: between early 20th-century European Modernism and US Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s; between figuration and abstraction; between the Old World and the New. He was born Vostanik Manoug Adoian in 1904 in the Ottoman Empire (which within a couple of decades no longer existed) to Armenian parents who had no country to call their own. Aged 16 he emigrated to the US to join his father, after his mother died of starvation shortly after escaping the Armenian Genocide. Gorky changed his name in the US and reinvented his family’s past.

The exhibition at Ca’ Pesaro is the first major Italian survey on the artist and will explore the dichotomies of the work produced during a tumultuous life cut short by suicide aged 44. The more than 80 works will range from early drawings and paintings clearly influenced by Cézanne and Picasso, to later near-abstract masterpieces, which paved the way for Abstract Expressionism.

The show will “illuminate areas still in the shadows of the history of the art of Italy, allowing us to explore in depth the osmosis between European and American painting”, says the co-curator Gabriella Belli.

Sean Scully, Madonna Triptych A (2018) © Sean Scully

Sean Scully: Human

Church of San Giorgio Maggiore

11 May-13 October

The church of San Giorgio Maggiore would seem to be the perfect location for Sean Scully’s art. Though he is a lapsed Catholic, he has pursued spirituality in his work from the start of his career in the 1970s.

San Giorgio’s programme is run by the Benedictine monks resident on the island, and Scully has responded not only to the beauty and structure of Andrea Palladio’s Renaissance church but also to the monks’ library of illuminated manuscripts. Scully has spoken of the power of ecclesiastical spaces for art: he has a permanent installation at the chapel of Santa Cecília de Montserrat in Catalonia. And he has long mined illuminated manuscripts as a source for his paintings, including the Irish Book of Durrow, responding to its purity and the meditative beauty of its patterns. Now, he has created his own illuminated volume for San Giorgio.

As well as the more familiar territory of Scully’s abstract paintings, including Arles-Abend-Vincent 2 (2015), an homage to Van Gogh, the display will reflect Scully’s increasingly diverse and experimental practice. It includes a vast new totemic sculpture with a skin of coloured felt, Opulent Ascension (2019), which responds to the Biblical story of Jacob’s Ladder and the 1990s film of the same name, and Madonna Triptych (2018) the first figurative paintings Scully has shown in decades.

Luc Tuymans, Secrets (1990) © Palazzo Grassi; Photography by Delfino Sisto Legnani e Marco Cappelletti

Luc Tuymans: La Pelle

Palazzo Grassi

Until 6 January 2020

Eighteen years ago, Luc Tuymans took the Venice Biennale by storm with his paintings for the Belgian pavilion that examined the country’s brutal colonial history in the Congo. Now he is back with this spectacular and wide-ranging exhibition.

Tuymans continues to explore troubling histories: 14 paintings deal with the Third Reich. But he says that they also evoke his feeling that “the whole constellation of the West is in dire straits” today. “The consequences of that specific era stretch all the way to what we are living now—the fact that anti-Semitism is cropping up in France, that there is a parade in Belgium that portrays Jews like they were portrayed in Nazi Germany.”

At the heart of Tuymans’s project is a central conceit: that images are unreliable, that they can offer us no more than a fragment of reality, and that our own memories, personal or collective, mislead us. “This idea of distrusting imagery, even my own, was there from the very, very start,” he says. “What is happening now [in the era of fake news] just proves me right.”