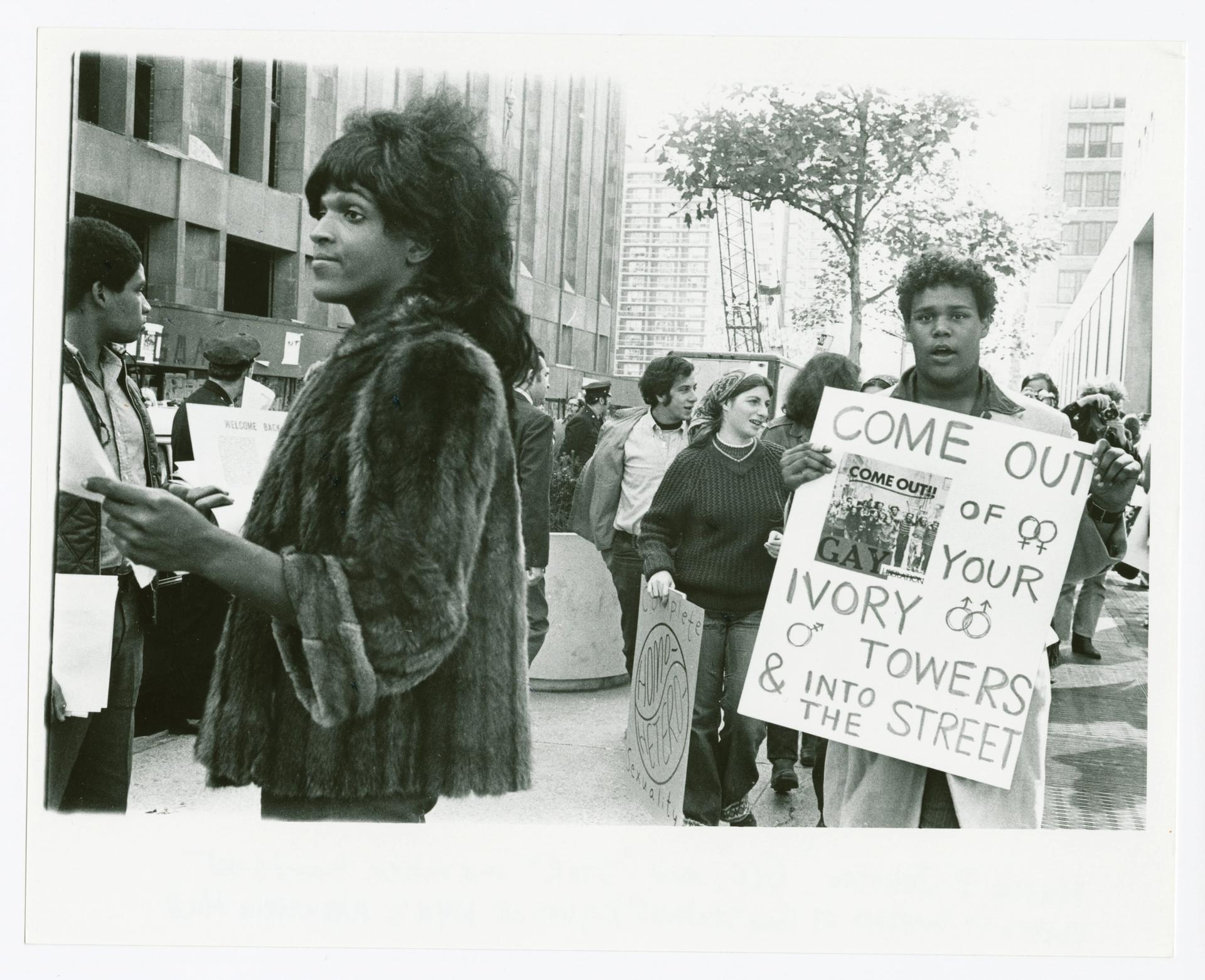

Untitled, around 1970. (Marsha P. Johnson hands out flyers in support of gay students at NYU) © Diana Davies / New York Public Library / Art Resource, NY

Fifty years ago, police stopped by the Stonewall Inn in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village during the early hours of 28 June 1969, checking apparently for alcohol law violations. But the employees and patrons of the gay bar resisted what had become regular harassment by the authorities, sparking six days of protests—and changed the course of LGBTQ+ history.

“The rebellion became the flashpoint that sparked the long uphill battle towards equality for all members of the gay community,” says the official website for the Stonewall Inn, which was designated a national monument by President Barack Obama in 2016.

The milestone anniversary of Stonewall this year has also thrown into sharp focus how artists and activists have engaged with LGBTQ+ issues and how queer cultural practices have developed since then. A large survey, Art After Stonewall, 1969-89—which opened jointly at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery (until 20 July) and the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art (until 21 July), and travels to Columbus and Miami—includes more than 200 works divided into seven sections, covering a wide range of topics, from gender and body, touching on fluid sexualities and identities, to Aids and activism.

“The exhibition focuses on the impact of Stonewall and the LGBTQ liberation movement on the art world,” says the exhibition curator and art historian Jonathan Weinberg. “The concept of impact is purposely broad and fluid. Some artists felt the effect of Stonewall keenly. Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, who was in the Stonewall bar the night of the raid, has made the event a crucial aspect of his art and the story he tells about his career.”

The exhibition focuses on the impact of Stonewall and the LGBTQ liberation movement on the art worldCurator and art historian Jonathan Weinberg

A central idea of the exhibition is that the act of memorialising and representing Stonewall was the key to the event being seen as a turning point, Weinberg adds. “Acts of representations, including taking photographs and making posters, paintings and sculptures about queerness, contributed not only to the focus on Stonewall, but helped to create and sustain communities of resistance, protest and affirmation.”

Indeed, Stonewall heralded a braver new world, prompting artists and activists to be more vocal. In 1971, the US painter John Button and the UK artist Mario Dubsky created a 32ft-long mural entitled Agit-Prop for the Gay Activists Alliance headquarters, located south of the Stonewall Inn. The piece, emblazoned with slogans like “Gay Power” and “Struggle”, was a rousing call to arms for gay rights activists. (The work was destroyed in a fire in 1974.)

Examples of this new solidarity can be seen in the joint show. The poet and painter Fran Winant, known for her poignant poem about the first Pride March (Christopher St. Liberation Day, June 28, 1970), focuses on the exhilaration of taking over the streets, but also the fact that the march was photographed, Weinberg says.

Other possibilities

The late African-American transgender performer Marsha P. Johnson was also a prominent figure in the Stonewall revolution, fighting back against police brutality on the night. “We include several portraits of her, and of her transgender activist comrade, Sylvia Rivera, who together founded STAR [Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries],” Weinberg says. Johnson, an HIV+ organiser with the Aids advocacy group Act Up, was photographed by artists such as Andy Warhol, Alvin Baltrop and Leonard Fink.

Daniel Ware (Cockette), 1971 Photo © The Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Courtesy Pace / MacGill Gallery, NY and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

The artists and filmmakers Tourmaline and Sasha Wortzel have created a film and video installation, Happy Birthday, Marsha! (2018), celebrating Johnson’s life and achievements through imagined scenes and archival footage. “Marsha was committed to imagining other possibilities despite being embedded in a landscape of relentless loss and violence,” Wortzel says in the catalogue for Art After Stonewall, 1969-89.

I think all marginalised peoples’ histories are hard to pin down, and queer history especially gets renarrated and reframed by every queer generation in order to fit the politics of the presentArtist and filmmaker Chris Vargas

However, “let’s not forget others, like [transgender activist] Miss Major and Stormé DeLarverie,” says the artist and filmmaker Chris Vargas. Fortunately, US artist L.J. Roberts’s new large-scale sculpture in the Brooklyn Museum show Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall (3 May-8 December), Stormé at Stonewall, pays tribute to the biracial lesbian activist DeLarverie, who, according to numerous witnesses, threw the first punch in response to police violence during the Stonewall tumult.

Avoid a master narrative

This rash of LGBTQ+ shows and events prompts debate about how queer history is documented or framed. Does the chronicling of contemporary gay lives need to be reassessed? “I think all marginalised peoples’ histories are hard to pin down, and queer history especially gets renarrated and reframed by every queer generation in order to fit the politics of the present. We should make room for this evolution and avoid the tendency toward a master narrative,” Vargas says.

One month after the demonstrations at the Stonewall Inn, activist Marty Robinson speaks to a crowd before marching in the first mass rally in support of gay rights, 27 July 1969 © Fred W. McDarrah / Getty Images

One notable example is George Segal’s Gay Liberation memorial to Stonewall, a sculpted tableau of two female and two standing male figures painted in white, was installed in 1992 in Christopher Park, opposite the inn. But, for Vargas, it is a mediocre marker for such a significant event. “I think Segal’s sculptures are inadequate memorialisations of the Stonewall riots. They are definitely of their time, when respectability politics reigned supreme.But they are literally a whitewashing—and cisgender washing, as well,” he says.

Last year, Vargas invited 12 artists, including Chris Bogia and Keijaun Thomas, to reflect on the Stonewall uprising, and create monuments commemorating the Stonewall revolution. The show at the New Museum, MOTHA and Chris E. Vargas: Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project, included artist statements and maquettes of the proposed monuments.

There are some caveats, though. In the catalogue for Art After Stonewall, 1969-89, Wortzel writes: “The Stonewall Riots are an important piece of our history, yet the rise in Stonewall’s mainstream visibility sometimes obscures the fact that we are part of a long and rich lineage of resistance and disruption that extends before and after Stonewall.”

For younger generations of artists, the impact of Stonewall can be more subtle. “I was born in 1965 and would have heard about Stonewall on the radio. It did not become a cultural reference for me until I was older,” says the Bronx-born artist Lyle Ashton Harris, who is showing his photographic triptych Americas (1987-88/2007) in the Grey Art Gallery show. The piece counters the stereotype of the mulatto character that was depicted in D.W. Griffith’s racist film The Birth of a Nation (1915), Harris says. “My own Stonewall moment came when I looked in James Baldwin’s novel Just Above My Head, which my mother was reading, and coming across the term ‘faggot’.”

The most impressive and important legacy of Stonewall can perhaps be seen at the Brooklyn Museum. Lindsay Harris, teen programmes manager, says that the exhibition there includes a reading room and resource centre, called Our House, which was organised in collaboration with the museum’s LGBTQ+ teen programmes and features a selection of texts and media about the Stonewall Uprising.

“This interactive archive and community space is intended to inspire visitors and offer continued learning for those who are new to LGBTQ+ history, as well as those who are deeply involved with queer and trans art, life and culture,” Harris says. In Trump’s America, there could not be a better outcome.