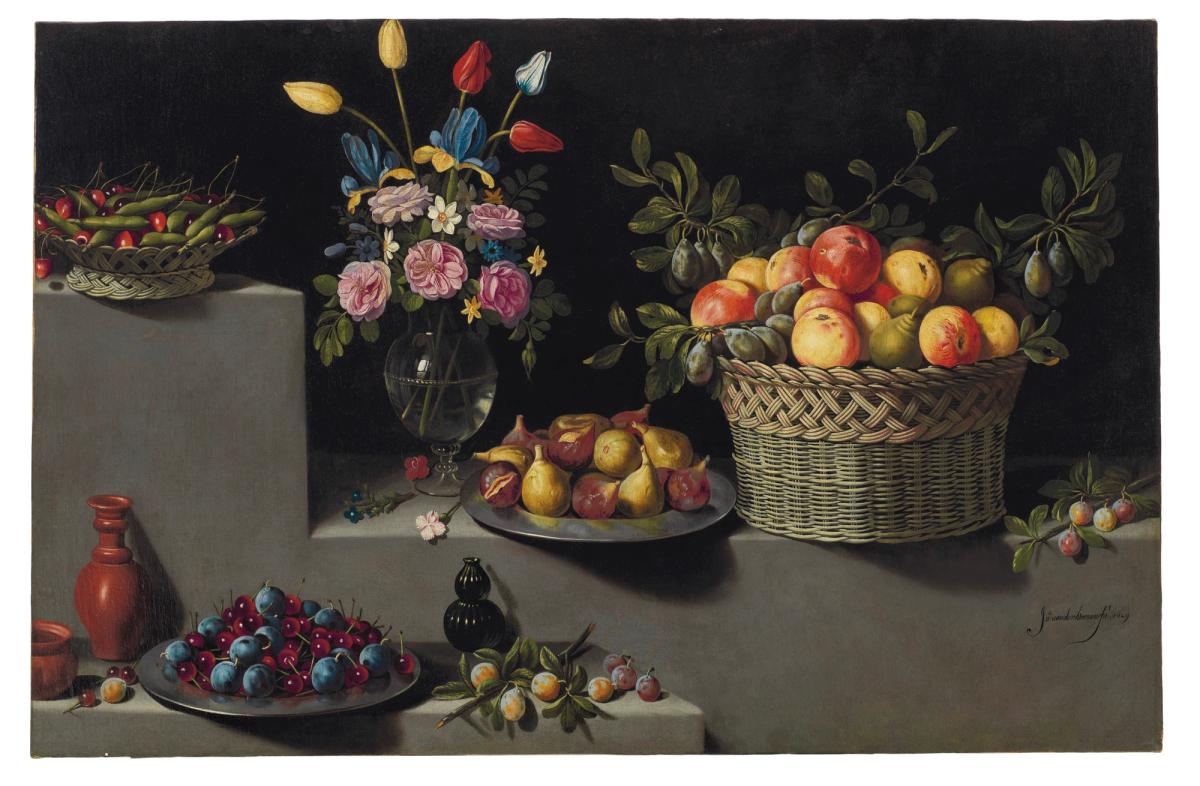

Works from two renowned US-based Old Master dealers hit the auction block today, marking the high point in an already solid start to the Classics week at Christie's New York. Richard Feigen is admittedly padding out his retirement fund by offering several pieces from his private collection, but the legacy of a dealer's acumen is truly being tested by the headline lots from around a dozen works from the estate of Herman and Lila Shickman. They include two masterpieces of Spanish still-life painting: Still life with flowers and fruit, signed and dated 1629 by Juan van der Hamen (1596-1632), which is estimated to fetch between $6m-$9m—a world auction record for the artist, but also potentially the most expensive Spanish still life ever auctioned—and Luis Meléndez’s (1716-1780) Artichokes and Tomatoes in a Landscape (estimate $2m-$4m).

For the last decade and a half the two pictures were on long-term loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and their sale is huge loss to its collection of Spanish paintings. Despite the Met’s richness in works by Goya, El Greco and Velasquez, examples by other artists have been surprisingly paltry, though in recent years there has been an effort to correct this with purchases of fine paintings by Pietro Orrente, Jusepe de Ribera and Luis de Morales. But aside from a large outdoor banquet by Luis Egidio Melendez hidden in the museum's downstairs Linsky galleries, Spanish still-life painting is all but nonexistent.

The institution maintained a good relationship with Shickman, which was strengthened through the part-purchase gift of Caravaggio’s Denial of Peter in 1997, and the gift of paintings by Michael Sweerts (2001) and Nicholas Maes (2004). But the Melendez and especially the van der Hamen were as needed as another former long-term loan—Danae by Orazio Gentileschi lent by none other than Feigen, who leveraged the Met's sustained exhibition endorsement to sell it to the Getty at Sotheby's in 2015 for $30m—but no deals were made then to secure them.

The Met is not unique in its underrepresentation of Spanish still-lives. When Shickman acquired his van der Hamen at Parke-Bernet in 1969 for $16,000—a fair amount of money at the time—and his Melendez, from London's Hallsborough Galleries in 1970, relatively few great examples of early Spanish still-lives existed in American public or private collections. There were some exceptions. In 1939, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston purchased two of Melendez's greatest table-top still lives of fruit and ham from Matthiessen in London for $300 (yes, $300); in 1945, Anne & Amy Putnam’s bought Juan Sánchez Cotán's great Still life with quince, cabbage, melon and cucumbers from New York dealer Jacob Heimann for the Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego, now the San Diego Museum of Art. A van der Hamen Still life with a basket of fruit was astutely bought by the Williams College Museum of Art in 1958; two further works by the artist were purchased by the Kress Foundation in 1955 (the great Still life with sweets and pottery) and 1957 (Still life with fruit and glassware). These were donated in 1961 to the National Gallery of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts Houston.

Following the Norton Simon Museum’s 1972 purchase of Francesco de Zurbaran’s unique Still life with lemons, oranges and a rose from Contini-Bonacossi for a reputed $3-$5m dollars, as well as the major touring exhibition Spanish Still Life in the Golden Age organised by William P. Jordan and Peter Cherry in 1985-86, international enthusiasm was roused for the genre, with the National Gallery London buying their first example, Zurbaran’s Rose and glass of water in 1997 and a considerably finer Basket of lemons by Francisco’s son Juan in 2017. Will the Met be able to catch-up purchase the Shickman masterpieces at Christie's at last, even if the price is buoyed by its own imprimatur? As the late dealer used to say: “Sometimes, collecting should hurt a little.”