The trend toward art-as-experience has proven a revenue boon to museums and institutions, if the record-setting attendance numbers at exhibitions like Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms are any indication. Yet the question remains whether these crowd-pleasing installations have an effect on the market for technology-driven, experiential art, which is being tested by its increased appearance at art fairs.

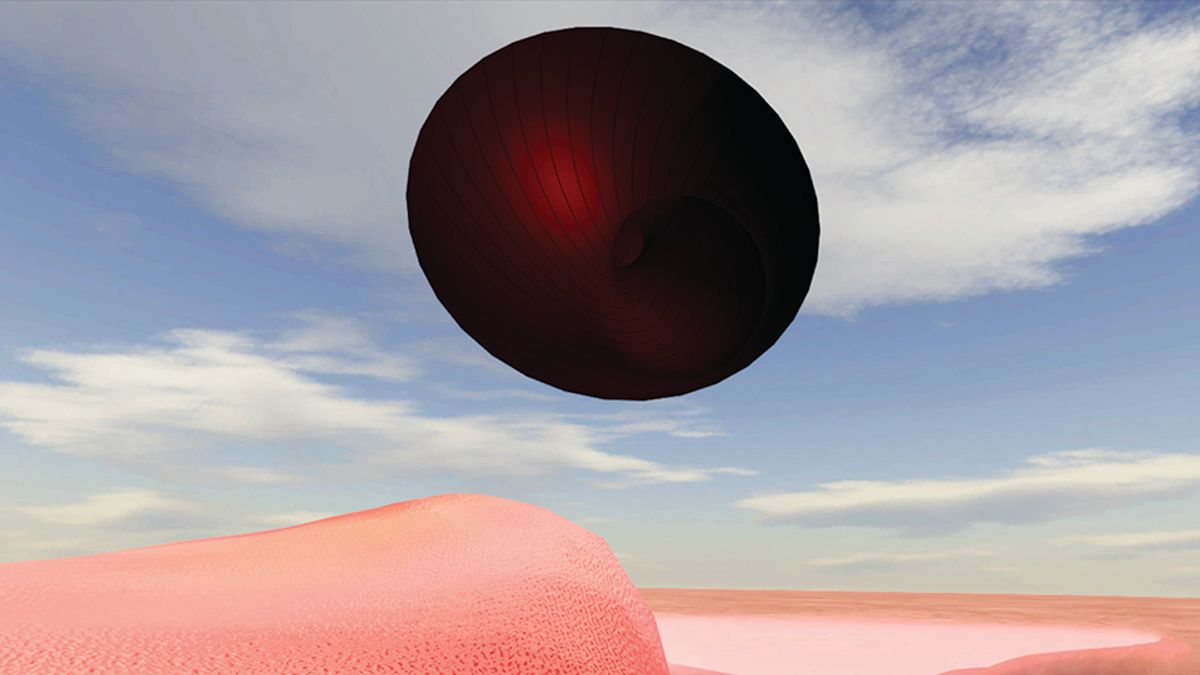

An entire section devoted to virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) works at Frieze New York this month raises this question succinctly. Curated by the art critic and director of Acute Art Daniel Birnbaum, Electric features pieces both from artists whose only medium is technology and from those with more traditional backgrounds in painting and sculpture who utilise VR to create new experiences of their work, including Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg, Anish Kapoor, Koo Jeong A, Städelschule Architecture Class, R.H. Quaytman, Rachel Rossin and Timur Si-Qin.

Visitors can experience the section’s two programmes, Alternate Current (AC) and Direct Current (DC), inside a special booth where they will alternate every half hour. “There’s a new generation of artists who can actually write code,” Birnbaum says. “But there are others who want to translate their traditional artistic and intellectual abilities to this new world.”

Electric seems to function more as an educational experience for collectors, however, since none of the works will be available for sale. “When a new medium like this appears—and it seems like it happens once or twice a century—no one really knows what to do with it yet,” Birnbaum says, adding that “I’m sure in a few years, it will be more professionalised and commercialised”.

“Many of these younger collectors are coming to the shows because of the VR but are then learning about the artist’s history and their other work,” says Sandra Nedvetskaia, a partner at Khora Contemporary, a VR production company that will partner with Hauser & Wirth at Art Basel in Basel in June. Indeed, when Khora worked with the Los Angeles-based artist Paul McCarthy to produce a VR experiment at the 2017 Venice Biennale, for example, “we saw this new wave of people buying the books on his sculpture and other art afterwards”, she says.

Yet VR works are often costly to produce and time-consuming to implement, according to Carla Camacho, a partner at Lehmann Maupin, which represents VR artists like Jennifer Steinkamp. “One misconception is that these are videos, but they are actually custom computer programs,” she says. “Once a piece is acquired, the client has to provide architectural plans so that it can be coded site-specifically.”

Additionally, because of the iterative nature of code, many VR and AR works are editioned, which keeps prices lower, often in the $10,000 to $300,000 range, according to Nedvetskaia. It is perhaps because of this road block to both understanding and distribution that exposure at fairs is helpful in translating these new media works to a broader consumer base. “The market is extremely young,” Nedvetskaia says.