Encouraged by the #MeToo movement, many have spoken about experiences of sexual abuse in the art world and elsewhere in the past two years. More often than not, the person speaking out is younger, and female. At the top end of the art market, a world obsessed by keeping up appearances, it is still unusual for a middle-aged man in a senior position to speak publicly about being abused as a younger man.

Which makes the revelations of Nanne Dekking, the chairman of Tefaf (The European Fine Art Foundation)—an organisation still regarded as a bastion of tradition—and the founder of the digital art registry Artory, all the more disturbing.

This urbane 59-year-old Dutchman appears the epitome of tailored-suited establishment, one most often heard espousing the benefits of blockchain and the need for transparency in the art world. Yet for over 30 years, Dekking has lived with the consequences of what he says happened to him at Castrum Peregrini, an Amsterdam society which, in the early 1980s, believed in the ancient Greek idea of pederasty, of older men “educating” younger ones. Until recently, he has never spoken about what happened to him. The members of this arcane organisation were the academic elite—historians, writers, poets, archaeologists and anthropologists—and the structure dictated, Dekking says, that each should have a “pupil”, normally aged under 18.

“It all happened in 1982-83 when I was in my early 20s,” Dekking says. “My now husband [the journalist Frank Ligtvoet] was part of the group—he was a young man and had joined when he was feeling lost. The only way they would accept my relationship with him was if I joined, too. A professor, an older man, was instructed to educate me, by reading poetry with me from [the German poet] Stefan George’s Der Stern des Bundes. But, unfortunately, that education came at a price. He would kiss me while I was reading the poems and then…he raped me. It still haunts me every day.”

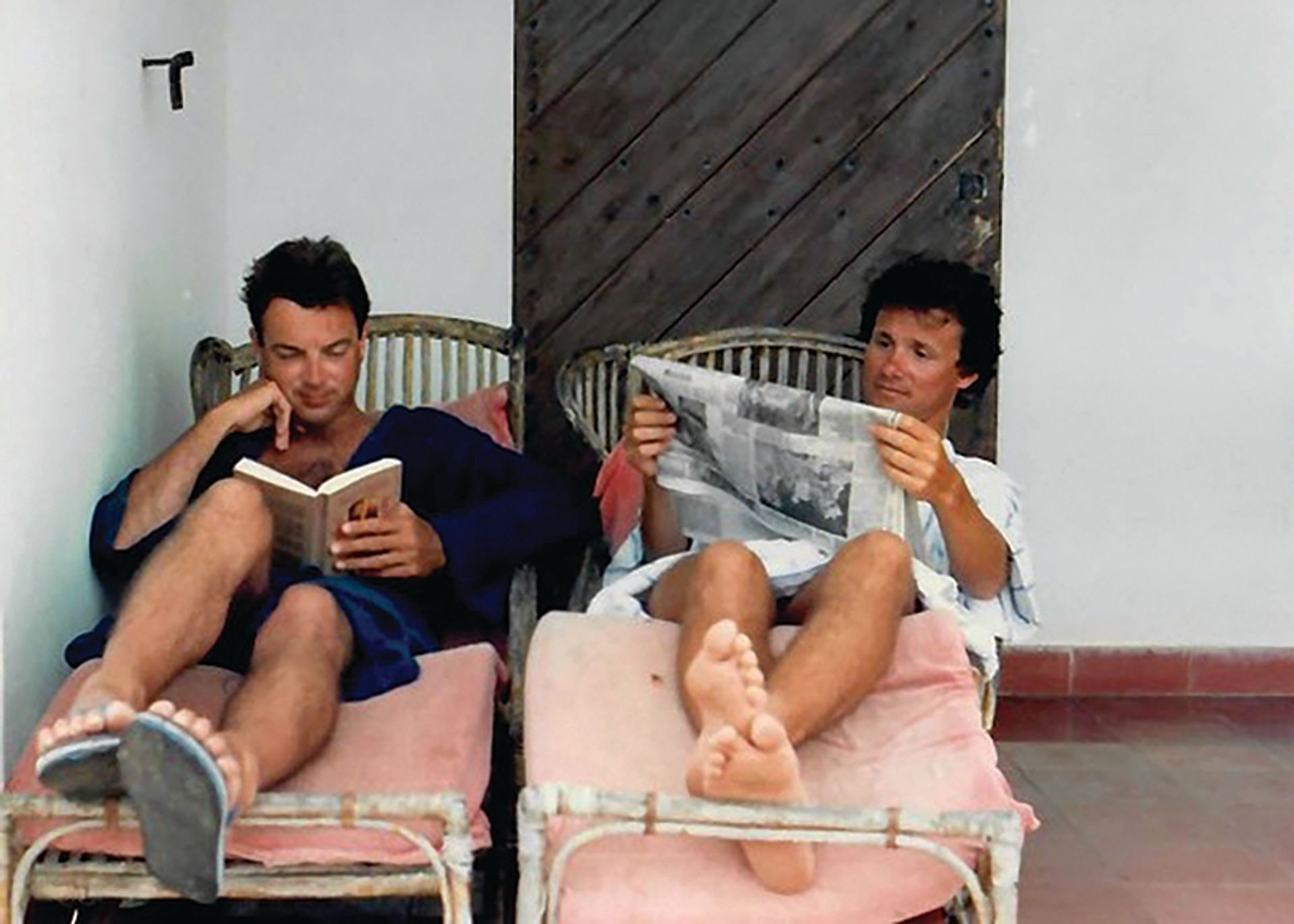

Nanne Dekking (right) with his husband Frank Ligtvoet in 1984. Ligtvoet was also a member of Castrum Peregrini; both left the organisation earlier that year because of their concerns. Courtesy of Nanne Dekking

Tip of the iceberg

In 1984, Ligtvoet decided to leave the cult when he and Dekking discovered that a 12-year-old boy, apparently the son of another member of Castrum Peregrini, was being made to sleep in the same bed as the person Dekking says abused him. (Dekking stresses that he does not know that any physical abuse took place.) “Two young boys were sent to stay with other members of the cult in Rome for several months,” Dekking says. “It made me sick. Because of all the research Frank did, which led to numerous publications, we now know that this was just the tip of the iceberg.”

Today Dekking is able to speak frankly about what happened to him, but it has not always been so. Until two years ago, Dekking and Ligtvoet had never spoken to each other about what went on at the organisation they were members of nearly four decades ago. “It was not until we heard Trump on television during the last election, talking about the women who claimed that they had been abused by him,” Dekking says. “His claim that all these women were lying as they had never spoken about this earlier resonated with us. It made us realise that we had been unable to talk about what happened to us for over 30 years.” Dekking and Ligtvoet first spoke publicly about his experience in the German and Dutch media in 2017, but have not spoken to the English-language press until now.

Dekking has received “hundreds of emails” from others who had suffered abuse in their past. “Many people have come forward and talked about similar experiences since reports of the abuse were published in the Netherlands and Germany. This prompted an ongoing independent investigation in the Netherlands led by two former judges and a secretary, Bert Kreemers, who was instrumental in the investigations into the Roman Catholic Church and sports world in the country.

Dekking says he is “furious” with those running the society today. Castrum Peregrini describes itself as a “cultural playground” on its website, which Dekking finds “sickening [as at the time he was there] it was elderly men grooming children for sexual abuse.” The society, Dekking says, “put a notice on its website saying that what happened to me did not happen on the premises and that, in 1982, it was not necessarily seen as sexual abuse.” After a request from his lawyer, it has since been taken down.

In an email to The Art Newspaper, the board of Castrum Peregrini says: “We feel very sorry for Mr Dekking for what happened to him and his partner in 1982-1983. From the very first publication of their story in 2017, the content of which came as a complete surprise to us, we have offered them cooperation and have taken firm steps to open up the past of the foundation. You can be assured that we will take steps according to the recommendations of the independent research commission on sexual abuse. The commission is currently working on the report that is expected in the course of this spring.”

Promoting honesty

In 1996, Dekking moved to New York for his partner’s job. He worked first as an art adviser before joining the dealer Wildenstein & Co as vice president, then becoming Sotheby’s vice chairman and worldwide head of private sales, a position he left to set up Artory. In 2017, he became chairman of Tefaf.

For over 30 years, the abuse “was the one part of my life I never spoke about, even though I had been brutally honest about everything else. When we adopted our two children—now aged 13 and 14—we had to be very open and honest about all aspects of our life. Yet we never spoke about this.”

A profile of Dekking, detailing the abuse, came out in the Dutch glossy magazine FD shortly before Tefaf Maastricht in March. When descending the stairs in front of hundreds queuing to enter the fair’s preview, he momentarily froze: “I realised maybe 20% of those people had read the article and knew what happened to me, and for a split second I panicked. Then, all of a sudden, I felt calm—it is what it is, it was not my fault.” Though Dekking was nervous about telling his story, he says the responses have been supportive and that he has “yet to have a negative response” from dealers.

Dekking advises others who have experienced abuse of any kind to “at least tell your best friend—it’s unnecessary to live with that burden for so long.” He does not think the art world is “rife with abuse”, but says: “In the art world most businesses are small, without an HR department, and most are family run, by people with huge egos. These things can happen more easily outside the corporate structure.” He pauses, then adds: “Dominance of leadership is taken for granted in the art world and what I want to say is that people who have experienced abuse—and not just sexual abuse—should speak out and try to be stronger than I was. Don’t allow it to happen to you.”

The Castrum Peregrini, whose headquarters is the central building in the photograph shown right. © Rokus C

Even if abuse is not rife in the art world, he concedes that it has a diversity problem. “Look at Tefaf—it’s run by an almost completely male group of people. Thankfully now we have a few women on the board but it’s still not enough. We need to represent more minorities.”

The experience in his youth has, Dekking says, given him “enormous drive”. Although he recognises that he comes across as supremely confident, he says that hides his insecurity: “I’ve always been scared that I wasn’t honest, that I was about to be found out,” he says. “If something like that happens early in your life you always worry that you should have done something to stop it, that you should have been stronger. Perhaps it has helped my career—I’ve always been tough on myself, I had to be perfect. But honestly I’d rather be a mailman than have experienced that and be where I am now.”

Some, he says, have sought to draw direct links between his past experiences and his current obsession with transparency in the art market. Rightly, he is wary of making such simplistic parallels—“It’s cheap to say I became obsessed with transparency because I was sexually abused”—but concedes that “it had an influence. I don’t want to come across as the guy who turned personal experience into a business…but I do naturally promote being open and honest with each other at work.” The art market’s lack of transparency infuriates him “because it is so counterproductive: why are we so secretive, when most of what we do is correct?”

Not that he thinks blockchain is necessarily the answer. “I’m a huge blockchain naysayer,” he insists: “I’m scared because a lot of people pretend blockchain technology itself will solve the problem. But the moment you start to totally ignore the current trust system and rely entirely on blockchain—saying you don’t need to know the buyer or the seller and on top of that create a cryptocurrency—that is not going to help transparency.”

The global art market, estimated at $67.4bn in 2018 according to Clare McAndrew’s Art Basel and UBS Art Market report, is relatively small. The figure “is the same as people spend on hotels in California in a year, or the annual revenue of Dell computers.” The art market has not grown for a decade, he says, and “is the only market that focuses on attracting those already buying the product, whereas the big challenge is to find more buyers.” In his view, “the reason most people don’t come into the market is because they only hear bad things about the art market. It needs to clean up its image.” Perhaps by speaking about what happened to him nearly 40 years ago, Dekking will help this process get under way.