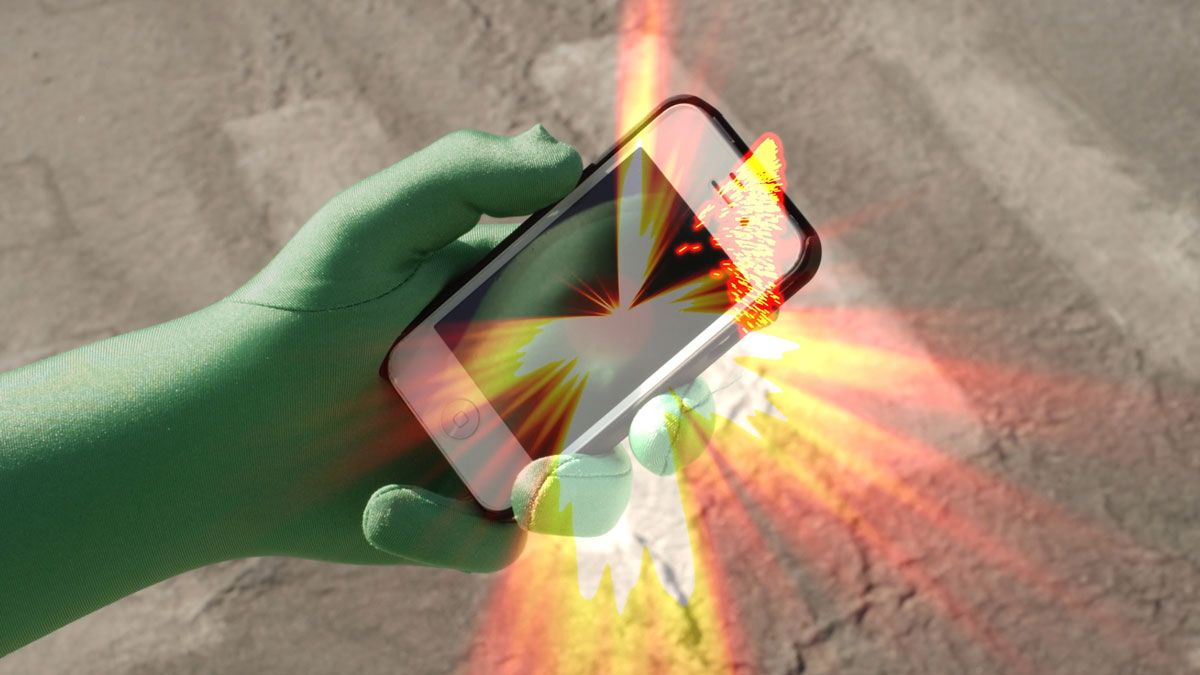

Hito Steyerl: Power Plants (until 6 May; free) at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery requires a bit of prep: to get the most out of it, you need a smartphone with the Power Plants OS and Actual Reality apps installed. But once you are armed with the software, it is an extraordinary show. Outside, you scan a sigil (a symbol associated with magic) and augmented reality representations of the gallery building appear on your screen showing infographics reflecting the impact of austerity and the rampant inequality found in the boroughs around the Serpentine. Inside are a series of video sculptures with screens featuring flowers forming and unforming based on information provided by Artificial Intelligence and neural networks. The augmented reality here features knowing asides from Steyerl as well as speculative quotes from a post-apocalyptic future where nature breaks through urban wastelands. But a very real dystopia of the present is at the core of the show. For example, there is qualitative evidence, as seen in the video interviews that underpin Steyerl’s project, of the effects of austerity and inequality on a domestic worker and a disabled man. As ever, Steyerl’s critique of the power structures surrounding and underpinning a gallery and its local environment delivers a balance of visual chaos, theoretical playfulness and, finally, a punch to the solar plexus.

Rembrandt’s Self Portrait with Two Circles (around 1665) has left the walls of Kenwood House and now temporarily hangs in the glossier settings of Gagosian Gallery on Grosvenor Hill for Visions of the Self: Rembrandt and Now (until 18 May; free), which marks a new alliance between the gallery and English Heritage. Rembrandt was as solipsistic as the next human-being and his painting, which asserts the self’s unfixed nature, is presented here as the first of many psychologically searching works to populate the Western canon. Everyone is here and it’s slightly overwhelming: Picasso, Warhol, Basquiat, Bacon. Some works are compelling—in particular an unflinching canvas by Jenny Saville—while others are trite: Koons’s gazing-ball Rembrandt portrait is even more exhausting in the presence of so much artistic genius. Self-portraiture has changed quite a bit since the 1600s, underlined somewhat unsubtly by an Instagram-based work by Richard Prince, but all roads lead back to Rembrandt (the star of the show is in the final room). Wizened, his searching eyes are mysterious and amorphous and beg for you to project a multitude of questions. The mutability of the self makes for a diffuse exhibition from which it is difficult to extract solid answers. Perhaps the only definitive thing one can take from this show is that Larry Gagosian possesses a very extensive and valuable address book.

For William Eggleston’s new exhibition 2 ¼ at David Zwirner gallery (until 1 June; free), the US photographer is showing a series of lushly coloured, rigorously composed, square-format colour photographs from the late 1970s. The recently-reprinted larger versions of images of cars, parking lots, individuals and family businesses were taken on a 2.25-inch medium-format camera as Eggleston travelled across Californian and the American South. “Red, there’s a lot of power in red. Just a dab, that’s all you need,” Eggleston said during a book signing on the opening day of the show as he flicked through the pages of the exhibition catalogue and alighted on an image of a vivid scarlet truck. For more on Eggleston’s japes at the book signing and private view, see William Eggleston's signature and style draws London crowds to David Zwirner.