When the Scottish artist Katie Paterson was invited in 2011 to a conference tasked with developing a public art programme for Bjorvika, a waterside area in central Oslo, an ambitious project came to mind. “I remembered an idea that I’d had before that seemed absolutely absurd,” she says.

The work was Future Library, which began in 2014 and will take a century to realise. In May 2014, 1,000 Norwegian spruce trees were planted in a forest near Oslo, and in just under a century’s time they will be felled to create the paper for an anthology of texts written by 100 authors. Each text is submitted yearly and will remain unseen until published in 2114.

What was the initial reaction to the proposal? “She hardly blinked,” Paterson says of Anne Beate Hovind, the project’s director. “Of course, it took a long time and a lot of effort to make it happen, but she just kind of grabbed on to it and managed to persuade people.” Local authorities have donated the forest plot, for example, and the foresters are tending it for free.

“I remembered an idea that I’d had before that seemed absolutely absurd”

The next task was to make sure the components of a 100-year work-in-progress will endure. Each author submits one physical copy of their text and a digital copy on a hard drive, Paterson says, during an annual ceremony in the forest (so far five authors have done so, including Margaret Atwood and David Mitchell). The physical manuscripts must be laser-printed on archival paper, which is longer-lasting than inkjet or other methods. A digital copy is held by the Oslo City Archives, “but the physical copy is the most important part”, Paterson says.

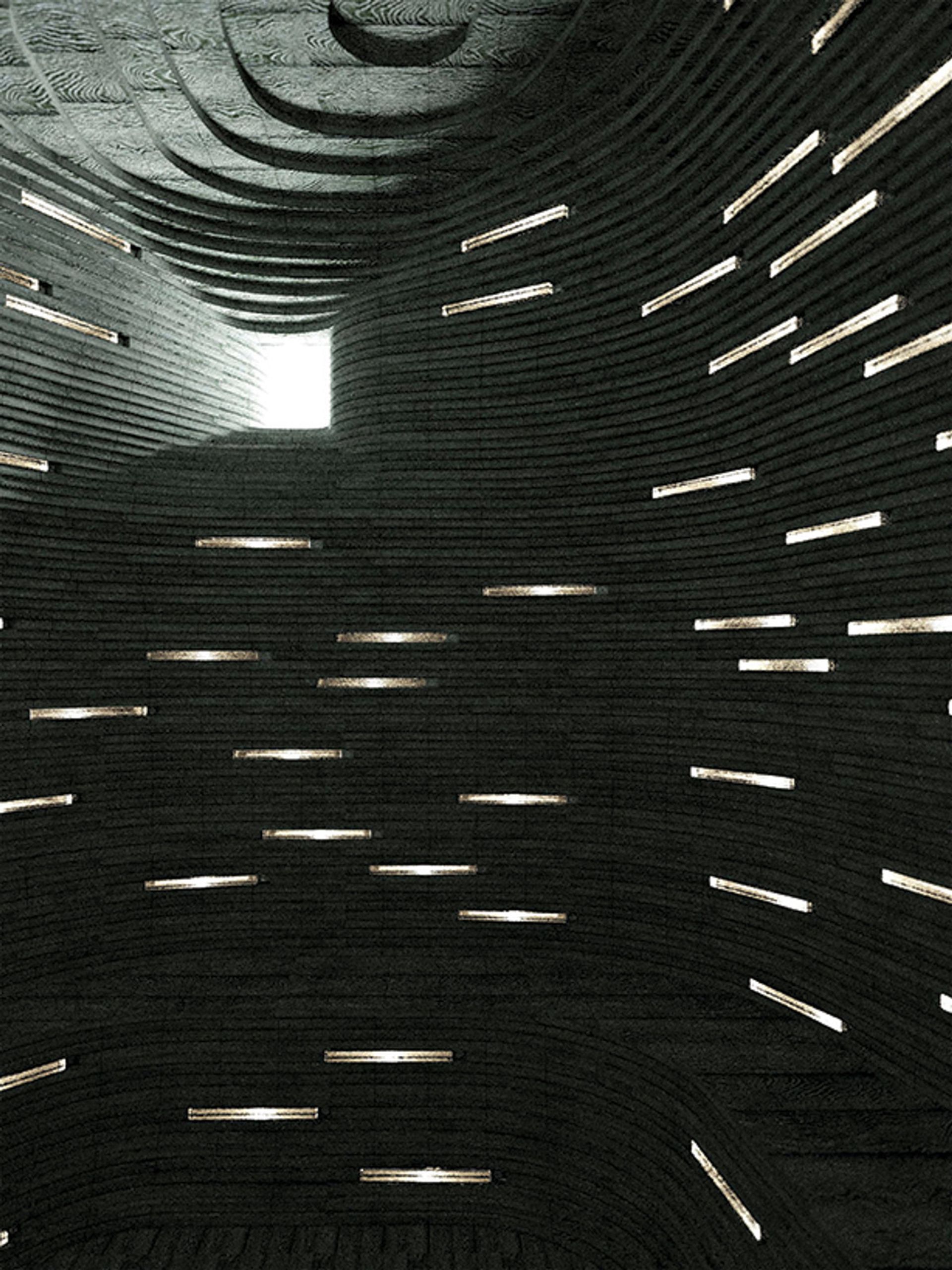

Silent Room, opening next year © Atelier Oslo/Lund Hagem/Katie Paterson

A room to securely store the manuscripts in steel security boxes until 2114 is being built as part of Oslo’s new Deichman library, due to open next year. Silent Room, designed with the architects Lund Hagem and Atelier Oslo, will have a window facing the forest 10km away and be lined with timber that was cleared to plant the saplings. The 100 drawers for the manuscripts are being handmade using cast glass with the author’s name and the year etched on to them, Paterson says.

At one point, bulbs used in ovens were contemplated as an option to light the individual drawers because of their durability, but in the end the project settled on fibre optics, which “have the advantage of having the light source away from the light”, Hovind says. “It is complicated, but old mechanical solutions seem best in the end.”

For a relatively young artist, Paterson is no stranger to the pitfalls of technological redundancy. In her current retrospective at Turner Contemporary in Margate, England, the bulbs in a 2008 work, Light bulb to Simulate Moonlight, can no longer be made because of the phasing out of incandescent, and soon, halogen bulbs. “If they break, that’s it,” Paterson says. While another work, History of Darkness (2010-ongoing), is, in theory, a never-ending archive of the darkness of different parts of space but “the thing that will probably end this project is the [redundancy of] slides”, she says.

The handmade glass for the drawers of Katie Paterson's Silent Room being poured last month Courtesy of Magnor and Anne Beate Hovind

Other works by the artist readily embrace ephemerality. For her latest project, First There is a Mountain, Paterson has created buckets in the shape of famous mountains that are being toured across the UK to 25 art venues and nearby beaches. At low tide, the public will be invited to make miniature versions of famous mountains such Kilimanjaro, Fuji and Stromboli. Even the buckets are designed not to last, being fabricated from bio-compostable fermented plant starch. “I just liked the banality of building sandcastles on the beach but then bringing together word-scale mountains that get washed off to sea with the tides,” Paterson says.

• A Place That Exists Only in Moonlight: Katie Paterson and JMW Turner, Turner Contemporary, Margate, until 6 May

• First There is a Mountain, various venues around the UK, until 27 October