The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) and the Eames Foundation say they have mapped out a conservation plan for the Eames House, the pathbreaking Modern residence built by the legendary mid-century designers Charles and Ray Eames on a bluff in the Pacific Palisades neighbourhood in Los Angeles.

The 1949 house and studio complex, which the couple designed and then lived in for the rest of their lives, is known for a steel frame structure clad in panels of varying colours and textures. It is celebrated as one of the best-known residences in the Case Study House Program, which was sponsored by Arts & Architecture magazine to promote the design of low-cost, prototypical Modern houses for post-war families. It has been a National Historic Landmark since 2006, and the public can pay to visit the grounds or house by appointment.

The role of the Los Angeles-based Getty Conservation Institute is to advise the non-profit Eames Foundation, which owns the house and will shoulder the conservation and repair costs. Made up of Charles Eames’s daughter and five grandchildren, the foundation plans to embark on a capital campaign keyed to the celebration of the house’s 70th anniversary this year, says Chandler McCoy, a senior project specialist at the Getty Conservation Institute.

“The house is in pretty good condition, but it’s fragile,” McCoy says. Corrosion afflicts the steel-framed window wall assembly of the home, he says. Inside, rubber tiles in the kitchen are cracked and have faded from green to an off-white, and custom-built storage cupboards with Plyon sliding doors have yellowed.

The Eames House is known for its integration into its sloping one-and-a-half acre site, graced by towering eucalyptus trees and a grassy meadow. The conservation management plan therefore takes a holistic approach, addressing not just repairs to the house and studio but also vulnerabilities in the landscape. A signature row of eucalyptus trees adjoining the house that were planted in the 1880s have reached the end of their life span and will need to be replaced with the same or a similar species, McCoy says.

Ray and Charles Eames in 1958 in their living room Julius Shulman/© J. Paul Getty Trust

The conservation plan also focusses on the collection of objects in the house, which includes Eames-designed seating, textiles, folk and Abstract Expressionist art, toys, seashells and other items that were grouped by Ray Eames in idiosyncratic tableaux. Excessive sunlight in the double-height living room, with glass panes facing south and east, have caused the fabrics to fade and left paper and plastic objects brittle, Mc Coy says.

“You have 70 years of sun pounding on the house,” he says. “Our recommendation is to control UV light—that’s the most important thing they can do.” The Getty Conservation Institute has recommended installing a UV film atop the glass. “The house can get very hot, and we recommend that they do some dehumidification and keep the air moving.”

Before beginning work on the conservation management plan, the institute guided the foundation in solving some pressing problems. The house rests on a concrete slab into which water had intruded, severely damaging the flooring in the living room. A moisture barrier was therefore installed atop the concrete, and the vinyl asbestos tile in the living room was replaced by a vinyl composition tile.

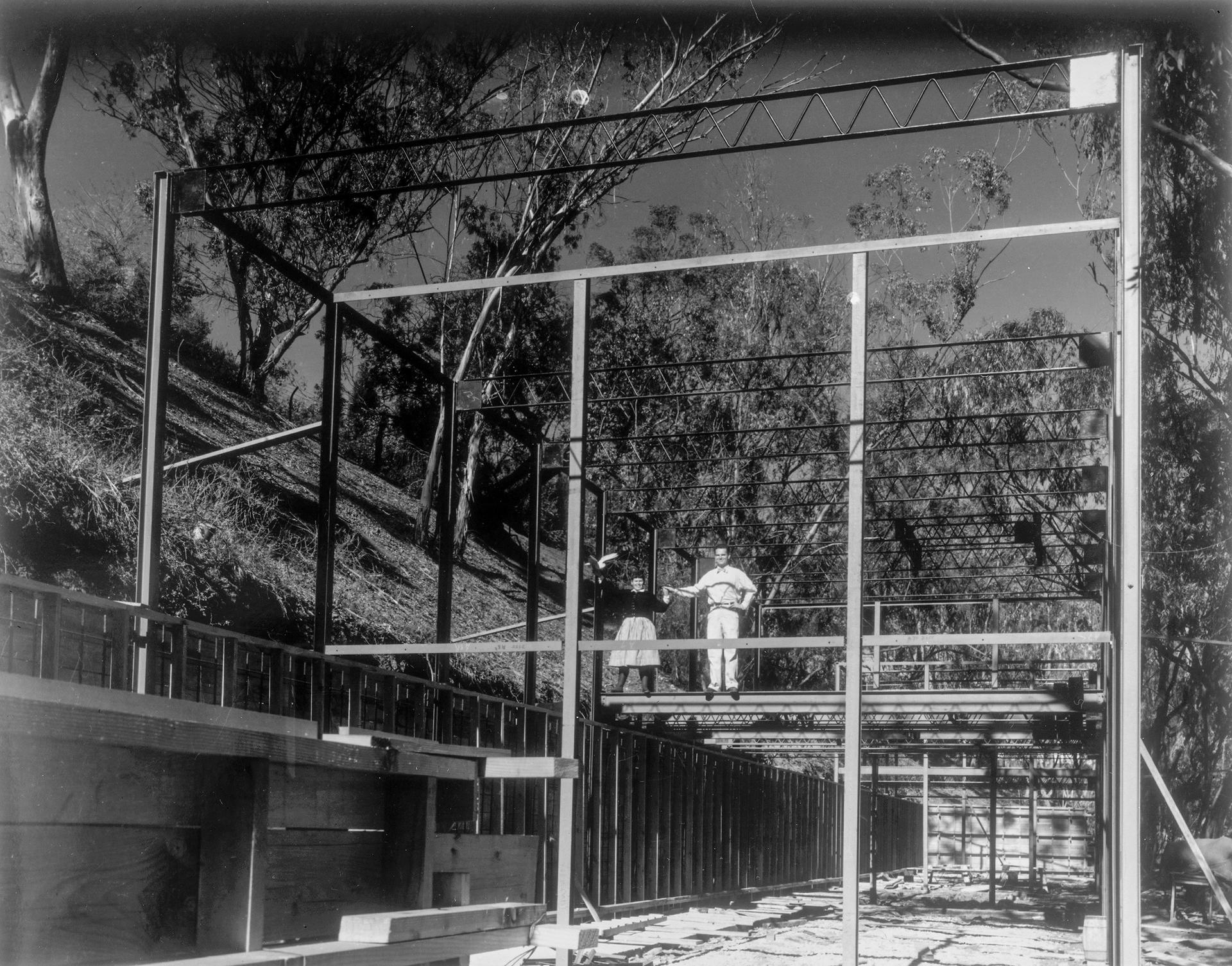

Ray and Charles Eames standing on the steel frame of their house in 1949 © Eames Office

The Getty Conservation Institute tackled the project through its Conserving Modern Architecture Initiative, which is overseen by McCoy and focusses on preserving 20th-century heritage.

Entering the house or studio, a visitor can immediately sense how the home served as an incubator for the Eames legacy in architecture, furniture, graphics and industrial design.

“It’s a charming house to be in because you have a mix of really interesting things like furniture and textiles they designed and a few pieces of art that are very fine,” McCoy says. “It’s fascinating: every surface has some interesting little kind of something that’s unique to the Eameses. They like to say that it’s as if the couple just stepped away from the house.”