Sometimes an exhibition can feel dramatically different—reborn instead of merely reconfigured—when it travels to a new city. That is the case with Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, 1963-1983, now at the Broad in Los Angeles (until 1 September) following its opening at the Tate in 2017 and stops at Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Arkansas and the Brooklyn Museum along the way. Part of the show’s novelty in Los Angeles comes from the fact that the art get a cleaner, more contemporary presentation because of the Broad’s sleek Diller+Scofidio architecture—making work that already feels urgent for investigating American class and racial unrest seem even more of-the-moment. Part of it is that the show includes works not seen since the Tate version, including major pieces by Betye Saar and Noah Purifoy, the artists who did the most in LA in the 1960s and 70s to make unforgettable art out of the trauma of the Watts protests and the rubble of the civil rights movement. A single gallery featuring their assemblages alongside examples by less celebrated California artists like Daniel LaRue Johnson easily feels like the culmination of the show, the moment when the narrative arc about scavenging meaning from social conflict becomes most clear.

At the same time, a couple of the artists in Soul of a Nation are getting major play at other museums across town. The draftsman-painter and educator Charles White is the subject of a major travelling retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (until 9 June; it first opened at the Art Institute of Chicago last year) and a more focused show considering his impact at the California African American Museum, Plumb Line, Charles White and the Contemporary (until 25 August). The Lacma show could have used a little more editing to make the case for his relevance—some of the roughly 100 works feel like mid-century newspaper illustrations—but his strongest drawings and lithographs approach the empathic power of work by Käthe Kollwitz.

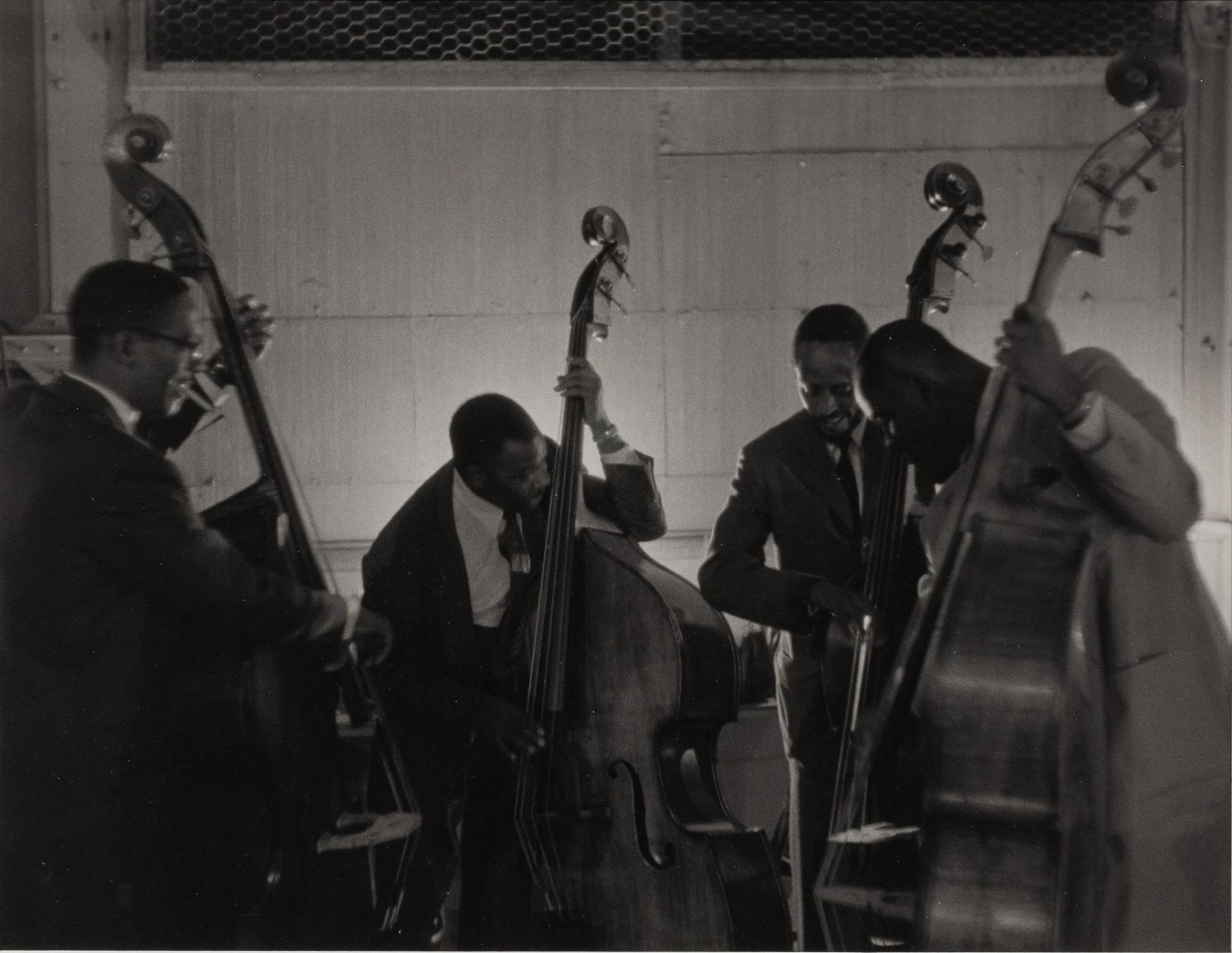

Also on the large side, but not too large, Roy DeCarava: The Work of Art at the Underground Museum (through 30 June) showcases nearly 50 vintage silver gelatin photographs from 1949 to 2000 selected by the artist’s daughter Wendy DeCarava. They range from candid-seeming New York street photography to stylised nature images (probably his weakest or most generic work), but most of all they reflect his ability to capture black men, women and children in relaxed moments, delivering a jolt of intimacy. His pictures of musicians are particularly dreamy, painterly, and intimate. Billie Holiday is shown singing or gritting her teeth—hard to say—Edna Smith is shown holding her bass, but eyes and mouth closed, and John Coltrane is caught offstage, maybe in between sets. All of these prints, which he took without the use of a flash and developed himself in the darkroom, are also studies in the different shades and tonalities of blackness: the dark skin of the subjects against the dark of the nightclub or evening setting, with just the glint of the eyes, smiles, watches or earrings, to define the forms. In this way, DeCarava began to do for photography what Kerry James Marshall continues to do for painting: making black-on-black canvases that force you to readjust your eyes and just possibly readjust your vision.

Roy DeCarava, Four bassists (1965) Courtesy of The Underground Museum