For nine years, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum has been foraging for answers to some of the most confounding questions raised by Minimalist and conceptual art from the 1960s and 70s: What makes a work genuine? If an artist decides he prefers an earlier or later iteration of his original work, which one should have pride of place in a museum? If an artist disowns a work altogether, how should the museum label and classify it?

The answers can be as complicated as the questions themselves, which spring from the Guggenheim’s acquisition in 1990-92 of a trove of nearly 350 Minimalist and conceptual works amassed by the Italian count and fervent collector Guiseppe Panza di Biumo. In some cases what Panza had purchased was not a physical work of art but the right to fabricate one from industrial materials according to specifications the artist set down on paper, often under the assumption that more than one version might be produced. The artists—most notably, Donald Judd—were sometimes dismayed by Panza’s fabrications, raising further questions about whether a work of art should be considered authentic.

Armed with a $1.23m grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the museum set out in 2010 to conduct rigorous research into questions surrounding the preservation and display of art in the Panza Collection. Jeffrey Weiss, then the museum’s senior curator, and Francesca Esmay, the Panza Collection’s conservator, pored over archival records and conducted hundreds of hours of interviews with artists, studio assistants, fabricators and curators while inspecting every inch of around 150 selected works of art. (Some of those works exist in more than one iteration.)

In the first phase of the so-called Panza Collection Initiative, they focused on works by Dan Flavin, Lawrence Weiner, Donald Judd, Robert Morris and Bruce Nauman; a second $1.25m Mellon grant followed, allowing the team to tackle Doug Wheeler, Robert Irwin, Carl Andre and Richard Serra. Now, the Guggenheim is drawing on an additional $750,000 Mellon grant to disseminate its findings to the public, culminating in a two-day symposium hosted this week in New York with the Getty Conservation Institute that drew over 200 art historians, curators, artists and others.

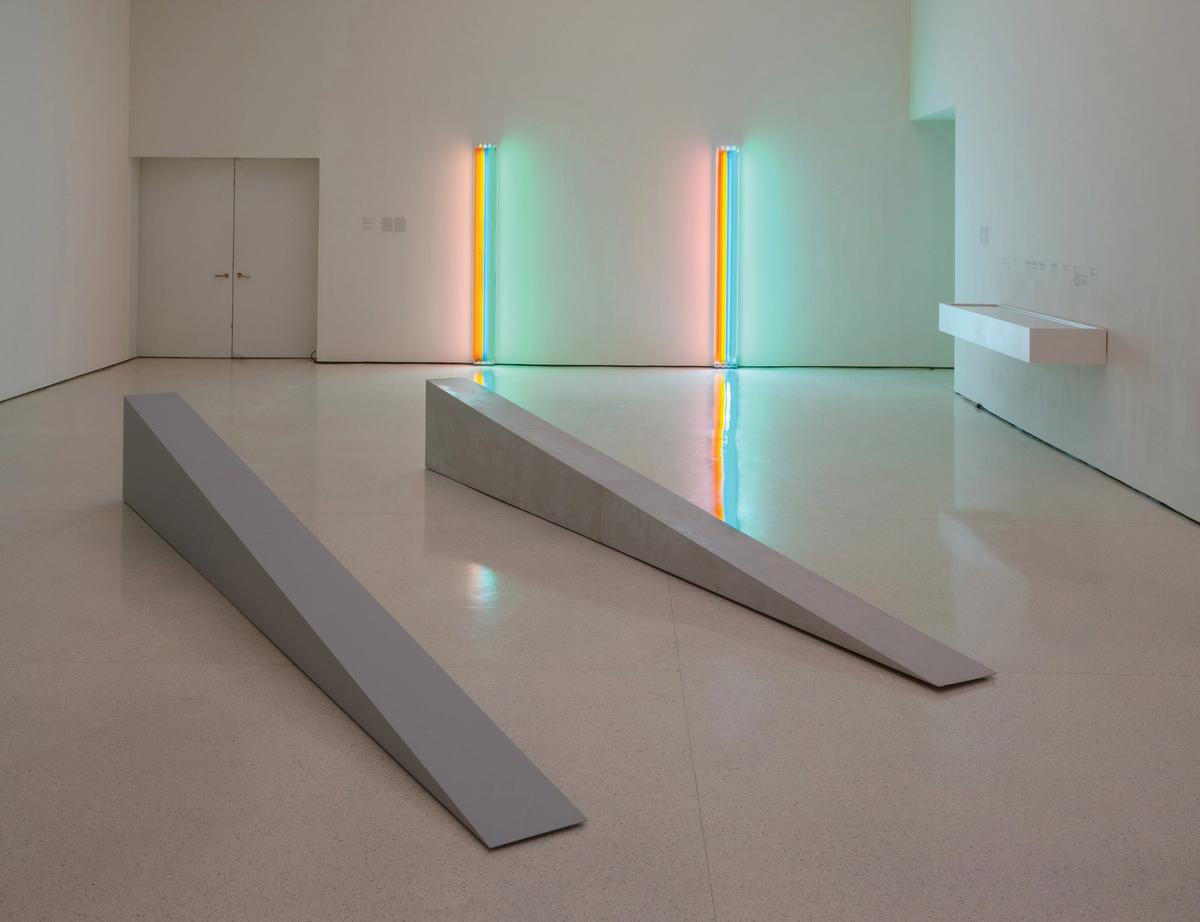

To highlight a few case studies, the Guggenheim invited participants to view selected works by Judd, Flavin, Morris and Nauman in a tower gallery. Among the pieces were two versions of Morris’s Untitled (Door Stop), a low-lying, elongated grey triangular sculpture. Morris, who died last November, was “extremely engaged” in the museum’s research and became “central to our mission”, says Weiss, gesturing toward the two iterations.

The surface of one, executed in fiberglass in 1965, is clouded and mottled. “You can’t clean it effectively,” says Weiss, who is now an independent art historian and curator. “If you repaint it, then you’re just basically hiding the original surface of the object, so there's no point in treating it that way when in fact you could make a clean new version. From Morris’s point of view, a new version is generally better than the old. He was the one who reminded us that during this period and especially in his work, there’s no such thing as an original.”

So at the direction of the artist, the museum manufactured a plywood version last year that appears utterly pristine. For Morris, the new work was the “privileged” one, Weiss and Esmay report. “To be sure, Morris wanted the re-fabrication to be the one that was used for display, period,” Weiss says. “There was not any second guessing or moments of hesitation.”

From Morris’s point of view, a new version is generally better than the old

Still, the museum itself will preserve both iterations—with the 1965 sculpture serving as an artefact that provides “a very useful and irreplaceable window into the character and material quality of the work early on”, Esmay explains.

In a radical step, the Guggenheim has sometimes chosen to “decommission” works that were executed in a way that flouted the artist’s wishes. A prime example was a 1988 version of an untitled work in plywood by Judd that Esmay calls “impossible to defend”.

The first version of the work, constructed in 1974 at the Lisson Gallery in London, was apparently destroyed. The following year, Panza purchased the work, known as Untitled (Lisson), from Judd as a set of specifications on paper from the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York, along with 15 other works by the artist.

In 1983, Panza lent the work—as a proposal on paper—for a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, which had it built by one of Judd’s approved fabricators, Peter Ballantine. Judd became furious when Panza declined to take possession of the built work after the show closed. The piece dropped out of sight and was presumed lost.

Relations between Judd and Panza worsened as Panza used an Italian fabricator to produce “deeply flawed” iterations of various other works that he had purchased on paper from the artist, including the 1988 Version of Untitled (Lisson), Esmay says.

A fragment of a 1988 iteration of Donald Judd's Untitled (Lisson) that the Guggenheim judged to have defied the artist's intentions David Heald/© Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Unlike the initial two versions, the 1988 Untitled (Lisson), made for a show in Geneva, was fabricated to fit a hall that was 60 feet in length—far longer than prior iterations. And unlike the others, it was “installed in such a way that it did not fit wall to wall”, Esmay says. The grade of plywood used did not measure up to the usual quality, nor did Panza inform the artist that the piece was being produced.

In a public essay in 1990, Judd excoriated Panza. “Nothing stops or shames him,” he wrote, calling some of his fabrications “conspicuously badly made”. Nor did Judd spare the Guggenheim, which was already under fire for deaccessioning works by Kandinsky, Chagall and Modigliani to help finance the Panza Collection acquisition, estimated at a reported $30m. “I don’t want to help the Guggenheim clean up its history and falsify mine,” he wrote. The artist died in 1994.

In 2016, with only the discredited 1988 version in its collection, the Guggenheim formally declassified the work. To date, the museum has decommissioned 16 works by Judd, 5 by Robert Irwin and 3 by Flavin, Lena Stringari, the deputy director and chief conservator of the museum, said at the symposium. That means that they are deemed to be “unviable”, she said: “They do not represent the artist’s wishes or the moral rights of the artist.”

In a public essay in 1990, Judd excoriated Panza. “Nothing stops or shames him,” he wrote.

Esmay explains: “We felt that the museum should in some way devise a category to appropriately hold and retain them for their historic value” while challenging their authenticity.

Then to the team's surprise and "complete delight”, she says, the approved 1983 version made for the Los Angeles MOCA show resurfaced at that museum, which shipped it to the Guggenheim. That prompted the museum to reclassify Untitled (Lisson) as viable. This week a portion of the 1983 iteration was exhibited to symposium participants in the tower gallery along with a fragment of the maligned 1988 version.

Sometimes, an artist is far less exacting than Judd was—or indeed, than curators and conservators may be—in sizing up later iterations of a work. Such is the case with Bruce Nauman’s None Sing Neon Sign, a sculpture in which the title words are fashioned from red and white neon tubing.

The original 1970 fabrication was shipped to the Guggenheim at the time of the Panza Collection acquisition in the early 1990s. The word “neon” in the white section was damaged in a 1999 exhibition at the museum, and eventually the 1970 sign creased to illuminate.

We’re really glad we went through the exercise of producing what we think is an exhibition copy that’s truer to the first version. But from Bruce’s point of view, they’re all equally viable.

As a result, the Guggenheim had Nauman’s approved fabricator for neon works, Jacob Fishman, create two exhibition copies, in 2005 and 2006, to be lent for shows at other museums. On view in the Guggenheim gallery, the copies clearly differ from the 1970 version: the red glass tubing is coated in phosphor, resulting in a less vibrant hue.

Four fabrications of Bruce Nauman's None Sing Neon Sign, 1970 (From left, 1970 fabrication that was refabricated in 2013; 2005 exhibition copy; 2006 exhibition copy; 2013 exhibition copy, with 2018 repair David Heald/© Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Then in 2013, Fishman repaired the 1970 version for the Guggenheim and fashioned a third, more faithful copy after sourcing a stockpile of the original transparent red tubing. Weiss and Esmay were gratified by the result. All four versions were on view this week for symposium participants.

Yet for the artist himself, the differences between the four iterations don’t seem to matter much, the team reports.

“We’re really glad we went through the exercise of producing what we think is an exhibition copy that’s truer to the first version,” Weiss says. “But from Bruce’s point of view, they’re all equally viable. These various objects were shown at various times in various shows, and all of it was completely OK with him.”

Esmay and Weiss hope that their research will prove illuminating for other museum professionals tackling myriad questions of stewardship and authenticity involving Minimalist and conceptual art.

“It’s been incredible for us in all these years how the works continue to pose questions,” Esmay says. “These aren’t static objects. We’ve just mapped it a little bit more, so that people in the future making decisions about this will have that much more to go on.”