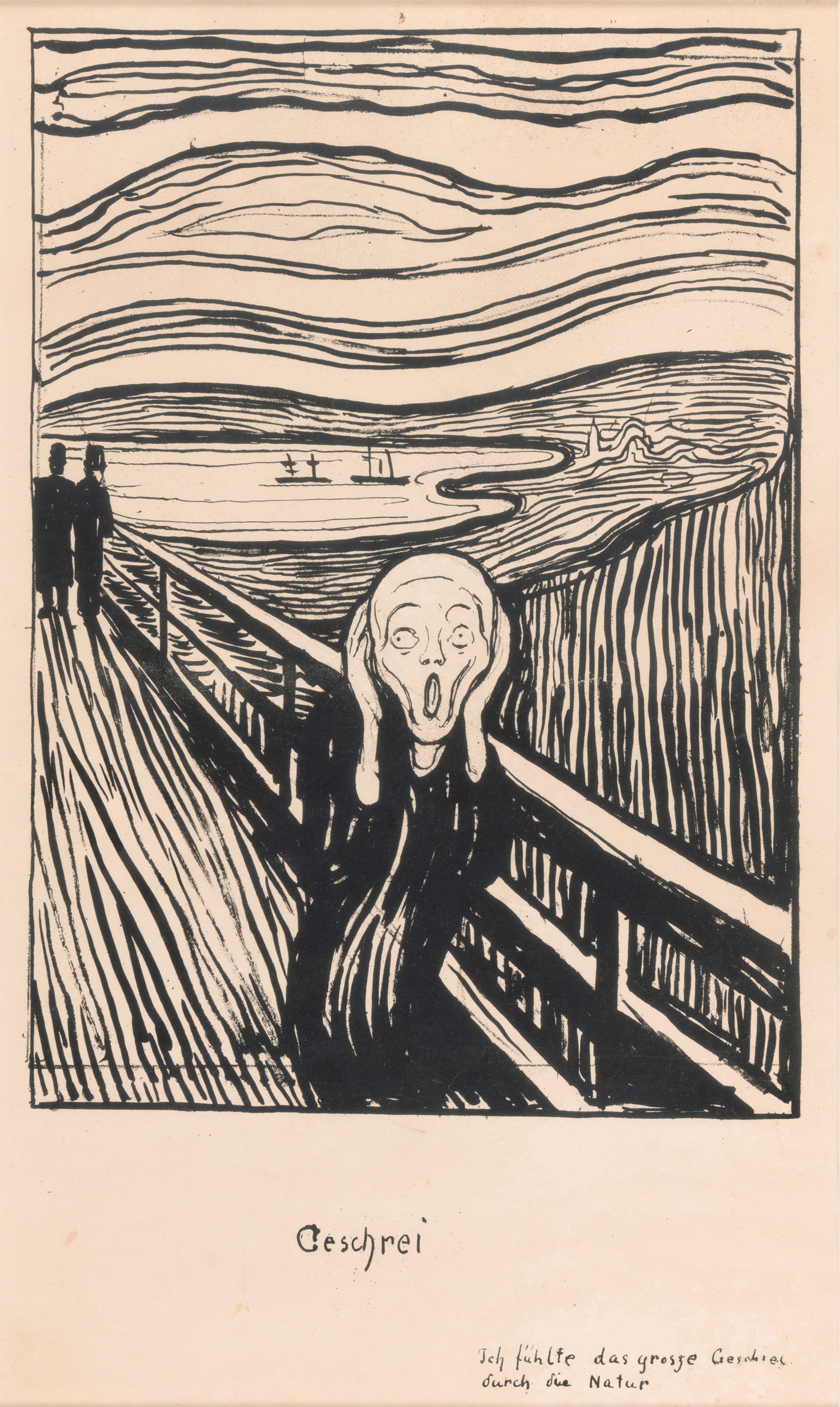

Edvard Munch’s black-and-white lithograph The Scream (1895) has already garnered headlines ahead of the British Museum’s exhibition on the Norwegian artist’s prints, which opens this week. But Giulia Bartrum, the show’s curator and assistant keeper of prints and drawings at the museum, is urging audiences to look beyond the famed depiction of despair. “This show is very much about putting The Scream in context—we show what Munch was like, who he was, what he was trying to do. The Scream is just one work in a sequence,” Bartrum says.

Organised in collaboration with the Munch Museum in Oslo, the show of around 80 works—mostly prints—will thematically follow the artist’s concept of the “frieze of life”. This cycle of the human condition that Munch developed included love and desire, jealousy, loneliness, anxiety, grief and death.

The survey will include an original lithographic plate, a copper plate and a woodblock—which Munch used to make the prints—that have rarely been shown. “The show will reveal the quality of Munch’s printmaking techniques and the calibre of the images,” Bartrum says.

The scale of the works will surprise people who are only used to seeing reproductions

Bartrum also says that the scale of the works will surprise people who are only used to seeing reproductions. “For example, [the work depicting] a woman called Sin—a scary looking figure with long red hair and green eyes—is much larger than you would expect and it is very striking,” she says.

There will be an image of The Scream outside the exhibition that Bartrum hopes people will use to take their selfies. “What I don’t want is people just endlessly not looking at the work and standing in front of it with a camera,” she says. In the show, the print will be displayed alongside items that examine the image’s composition: a photograph of Ekeberg, the location of The Scream; images of the particular type of red cloud formation prevalent in northern Europe, that may have inspired the work’s sky; and a preliminary drawing of a closely related work called Despair (1892).

Edvard Munch's lithograph print The Scream (1895) Private Collection, Norway; Photo: Thomas Widerberg

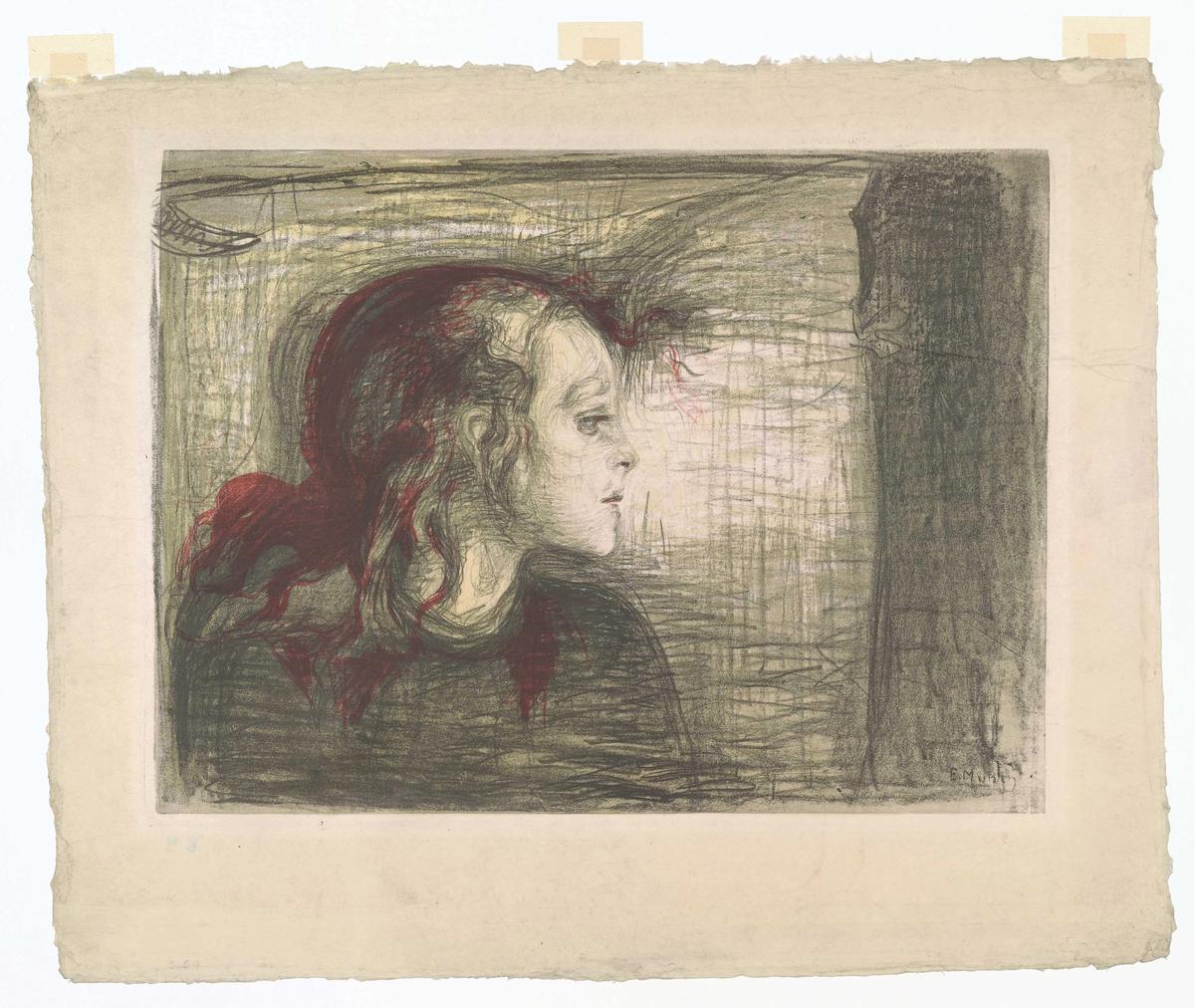

So what works should visitors focus on to see Munch at his best, if not The Scream? “The Sick Child lithograph is absolutely beautiful,” Bartrum says. “He is representing the moment of death that he recalled from his sister who died of tuberculosis when he was 13. He focuses on the white space and on the head of the girl, sinking into oblivion.”

The exhibition is sponsored by the AKO Foundation, set up by the Norwegian collector, Nicolai Tangen.

• Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, British Museum, London, 11 April-21 July