From my first minutes in the Van Gogh Museum’s show, Hockney-Van Gogh: the Joy of Nature, I started asking myself questions. I watched the introductory video, on a big screen, beautifully produced, with the old duffer David Hockney himself waxing about “endless inspiration and joy in nature”, cutting to scenes of soothing, rolling English hills, back to a jolly, friendly Hockney dabbing his palette. I thought: “Is this a marketing video for a retirement community?”

My mind wandered a bit as springtime’s green fields and pretty woods unfurled. Then, I heard Hockney exclaim: “It’s like nature’s having an erection... and it only lasts two days...”

“Whoa.” I lurched backwards. On watching it again, it was spring in England that lasted two days, the span of its metaphoric erection left unstated, the stuff of dreams. “Where’s this going?” I was talking to myself at this point. It turned out, no place libidinous. The show’s a tame, though colourful, bit of fluff, so blatant that it put me in the frame of mind to ask more questions.

They prove that the bigger the art, the more insistent and persuasive its mediocrity

First and foremost, what do Hockney and Vincent Van Gogh really have in common, aside from citizenship in the brotherhood of man, sometime landscapists and extraordinary colourists? It might be the stickler, stodgy art historian in me but the “deep, intense longing felt by both artists throughout their careers for new vistas and new worlds” means, to me, not much. Hockney was inspired by Van Gogh to paint outdoors, “just to find a new kind of language...and I tried to create new space”. Van Gogh savoured “that flat landscape in which there was nothing but...the infinite...eternity.” That’s the catalogue’s take (ellipses not mine). The catalogue and show are filled with bromides. It’s a lot of baby talk.

Besides, as Hockney reminds us in the video, “there’s love in those paintings, isn’t there?” I squirmed. Please, not spring in England again. My thoughts strayed to Yvonne De Carlo singing ‘I’m Still Here’ when she was in the musical Follies. Hockney’s been around for a long time. Whenever I look at his art, I quickly start thinking about something else: movie stars, Julius Shulman photographs of Neutra-designed houses, Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One. Just plopping himself in Hollywood makes an Englishman something he wouldn’t be if he moved to Buffalo. Or maybe the work is just to be glanced at.

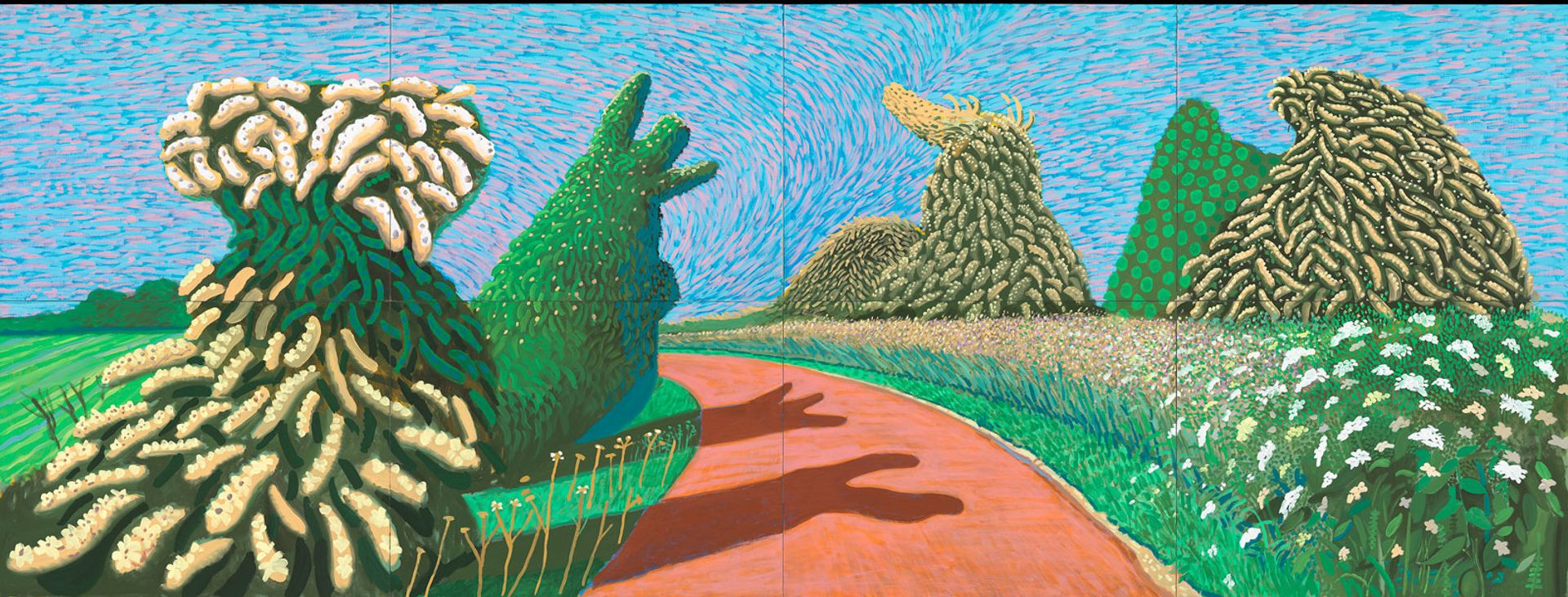

"Like nature’s having an erection": David Hockney's May Blossom on the Roman Road (2009) © David Hockney, Photo: Richard Schmidt

Van Gogh and Hockney are distinct and separate propositions. I suppose there’s a tome the size of the Manhattan phone book about what they don’t have in common, like their centuries, milieux, trajectories, biographies, philosophies, impulses and mental conditions: since one was psychotic and the other the refreshingly grounded Hockney. What the show tells us they have in common is either flights of fancy or a forced march from Filippo Brunelleschi to Fra Angelico to Eugène Delacroix to J.M.W Turner to Jean-François Millet to Van Gogh, then leaping over the vast oceans of Modernism, Dada and Pop Art to Hockney.

Van Gogh’s look at nature is visceral. It’s nature in the raw. Hockney’s is cheerful, playful, even nostalgic, which is why some of the late things look like folk art. I once had an old Yankee cousin desperate to establish a blood link to Charlemagne. Family resemblance not doing the trick, he deployed a legion of charts to establish a link that was as tenuous and hypothetical as it was inconsequential. As we say in rural Vermont, “wishin’ ain’t gettin’”.

Vincent van Gogh's Field with Irises near Arles (1888) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The show places a few nice Van Gogh paintings from the museum’s collection here and there but their presence is suggestive. There’s no tough, Jesuitical point-on-point comparison. The show’s almost all Hockney work from the last ten years. Almost all of it belongs to the artist or the David Hockney Foundation. Is its next stop the marketplace? If that’s the case, it’ll go there spruced up with the incandescent, contrived but immensely attractive lineage the Van Gogh Museum has bestowed upon it.

The Hockney landscapes on view are enormous. They prove that the bigger the art, the more insistent and persuasive its mediocrity, unless it’s a Baroque altarpiece. They’re billboards for spring with none of its energy, nuance, warmth or delicacy. They’re wallpaper more than anything and look like the stage sets for which Hockney is justly renowned. They look like the big springtime watercolours of the great Charles Burchfield or Milton Avery—but flattened by a truck.

Small landscapes done in watercolour or charcoal are installed tightly in blocks of 25, like sheets of themed postage stamps. We’re not meant to look at each one individually but, like a billboard, at overall effect and instant messaging. I defied expectation and looked at them closely. They’re nice but nothing remarkable. There’s a big gallery of video art depicting the four seasons. I liked it, but why was it there? Where’s the storyline?

David Hockney's Woldgate Vista, 27 July 2005 (2005) © David Hockney, Photo: Richard Schmidt

I was keen to learn more about massive prints that started as iPad drawings. I’m fine with using new technology. Good for Hockney. They look like lithographs or even stained glass. What does the new medium mean to Hockney, aside from allowing him to draw in bed? That’s about as profound as the show gets.

Hockney’s a fine artist and an unusual variant in the Pop Art movement. Yes, his sociable paintings have a vibrant palette and nothing to upset the viewer, much less deeply challenge him. They’re not fatuous, though, and they’re blessedly free of kitsch. It’s California Cool art, Pop Art in its Art Deco phase, to string bits of jargon together. It’s bright, fun, a little carnal since he’s Hollywood and gay, but rigorous and distant, too. Hockney brought a touch of class to Santa Monica, as English ex-pats always do. The bar’s low there, so an English accent and English reserve confer instant élan.

Hockney has always been a serious, hard-working, free-ranging artist, too. He’s weathered 50 years of art fads. In the late 1960s into the 1970s, his arch, hip swimming pool pictures and portraits of collectors and connoisseurs as well as self-portraits combined a cool glam, an of-the-time psychedelic palette, and just enough monumentality to impress seriously. There’s good social commentary there, too, since clothes, hair, setting and languor together evoke a specific zeitgeist.

David Hockney painting May Blossom on the Roman Road (2009) David Hockney, Photo: Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima

Today, he’s a brand. He and his work are famous for being famous. Right now, he’s in the record books, and the news, for being the most expensive living artist at auction. The work in question is one of the swimming pool pictures and sold recently at Sotheby’s for $90m. That it displaced a Jeff Koons sculpture in the big-money department says something about Mr. Market’s taste.

This brings me to my last question. Why on earth is the Van Gogh Museum doing this show? It’s got a brand, too. It’s a distinguished museum in a major capital championing the work of the country’s most important artist, Rembrandt aside. I’ve done two shows there: a splashy but good show on Impressionist oil sketches and a decidedly egghead show on Millet’s drawings and pastels. It’s a serious place, but this isn’t a serious show.

I don’t know what the show’s financial model is or how the museum is funded. As far as I can tell, all the Hockney art on view, aside from one big loan from the Pompidou Centre in Paris, comes from Hockney himself or his foundation, which was established to promote Hockney’s work. As foundations go, this objective isn’t the height of altruism. There’s no multiplication of loaves and fishes to feed the poor. In America, these artist foundations have immense tax and marketing advantages.

Vincent van Gogh's The Harvest (1888) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

One last question. Are there enough degrees of separation between the show as a scholarly, educational enterprise and Hockney Inc’s promotion of itself in the commercial marketplace? It’s a useful question on many fronts, among them the fact that the museum’s very good director is headed to London to lead the Royal Academy of Arts.

• Hockney-Van Gogh: the Joy of Nature, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until 26 May

• Brian Allen is an art historian and former director of the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts