In the decade between 2006 and 2016, more than half of London’s queer venues shut their doors. The 73 closed-down gay bars, lesbian-run theatres and sex clubs are mapped out on an interactive board as part of an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery that combines archive material, academic research and artworks to chart the shifting contours of the capital’s queer scene.

“Public space in London has changed”, says the co-curator Nayia Yiakoumaki. “Today we supposedly have a democratisation of space, an increased tolerance to queer causes; anyone is now seemingly welcome anywhere. But places that attract communities who don’t necessarily want to hang out in a Starbucks all day are less active.”

Yiakoumaki makes clear that this is a show about gentrification. Beginning in the Thatcher years, it tells the tale of a sterilisation caused by market-led redevelopment and skyrocketing rents that push out vulnerable communities. Queer spaces—which Yiakoumaki qualifies as places where queer people have historically gathered to socialise, organise, and protest—have changed dramatically since the 1980s. Where formerly police raids shut down queer venues, today these spaces are threatened by the insidious forces of neoliberal economic policy.

The First Out café, a fixture on London’s gay scene for 25 years, closed in 2011 Courtesy of Malcolm Comley and Robert Kincaid

The exhibition draws on the data and historical records compiled in a 2017 report LGBTQ+ Cultural Infrastructure in London: Night Venues, 2006-Present, produced by Ben Campkin and Laura Marshall of UCL Urban Laboratory. The findings of the report form the foundation upon which the archived material—films, leaflets, rejected planning permissions from queer venues that have closed, or resisted closing—is placed together with existing works from a handful of queer artists: Tom Burr, Prem Sahib, Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Evan Ifekoya and Ralph Dunn.

Tom Burr—the oldest artist in the group—is exhibiting a work titled Blue Shoe Mirror (2005), a mirror placed at foot level which, he says, “toys with notions of fetishism and fragmentation of identity”, along with a short poetic text about his own body and architecture. A notable part of Burr’s oeuvre deals with the process of archiving, such as his Bulletin Boards, which collate found images, research material and text created by Burr to physically record various public spaces such as parks and restrooms. “Historically queer communities have existed within precarious spaces and conditions, always in threat of being obliterated, erased”, Burr says, adding that this gives a greater significance to their need to “actively build a recorded history where there is none, both for a sense of present identity and also as an act of continuity into the future”.

Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hasting's The Scarcity of Liberty (2016) Courtesy the artists and Arcadia Missa

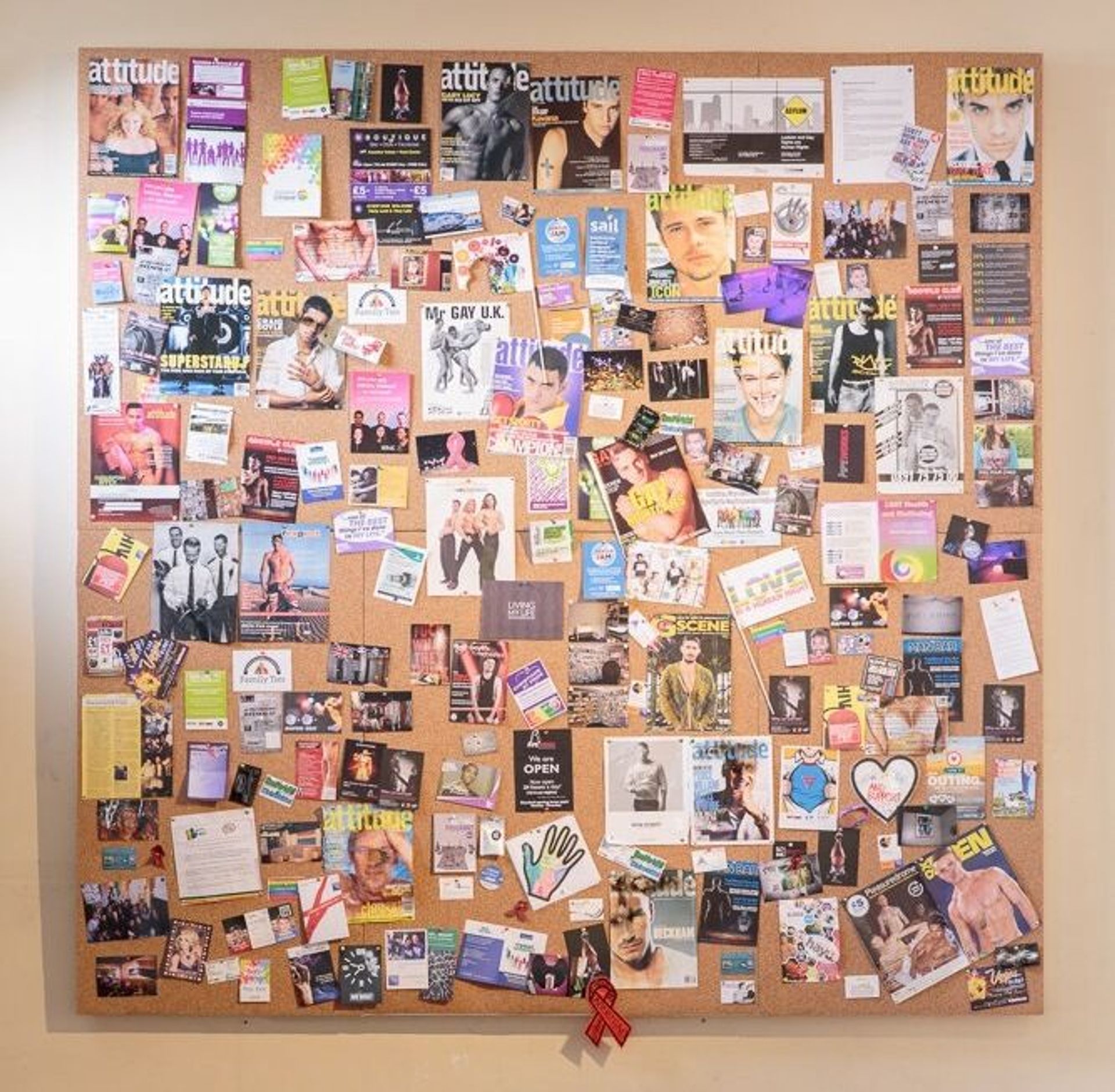

Archiving is also central to the practice of the show’s youngest artists, Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings. One of their featured works, The Scarcity of Liberty #2 (2016) consists of a cork-board pinned with ephemera ranging from mental health pamphlets to drag-show flyers. The work, Hastings says, functions as a blueprint for how a queer space could serve its community, preserving the functions of these spaces for future reference.

Though the materials on this board may speak to the care and solidarity found within these venues, Quinlan and Hastings’s work also examines the divisions that exist within the community. Present in the work are cut-outs from the gay men’s lifestyle magazine Attitude, intentionally showcasing a specific type of person—a cisgender muscular white gay man. The work is meant to shine a light on the comparative higher visibility this group possesses within the queer community, mirroring data from Campkin’s study which found that spaces catering to Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Groups (Bame) closed disproportionately and that venues that resisted closing tended to be owned by white gay men.

Yiakoumaki hopes that the exhibition will encourage a deeper awareness of these complex issues that affect queer spaces today. The Queer Spaces exhibition will coincide with London Pride 2019 and although the rate of closures of London's queer venues has now stabilised, Yiakoumaki is wary of pronouncing a celebratory tone. She notes that even when a queer space in London remains open, it has often been forced to change into a venue focused on profit instead of serving a community: “There might be a queer venue that is still there and full of people. But if there is a huge corporation behind it, if the drinks are £10, is that necessarily a good thing?”

Similarly, for the co-curator Vassilios Doupas the exhibition is "not so much about LGBT rights or a celebration of these spaces but rather about asking the question—what is going to happen if these spaces are lost, or transform into something super commercial?” To this effect, Doupas differentiates between the terms "gay" and "queer" to explain how the exhibition looks to challenge the destruction of public space within London. “Queer for me is not just a description of your orientation, it is also about not fitting in with established models and prototypes," he says. "By 'queering' something you are trying to subvert it, so I think that the exhibition is very much about trying to subvert a specific stereotype that is the product of neoliberal policies”.

Art institutions and museums tend to be slow at addressing society’s needs, Doupas says. By examining a narrative not often registered within the canon of art history, the gallery makes a progressive step forward in showcasing what an institution can exhibit, and the social ideals it can champion. Indeed, if a key value of queer venues has been to provide a safe space in which to organise and gather information, then it seems that the Whitechapel Gallery will become, if only for a few months, London’s newest queer space.

• Queer Spaces: London, 1980s-Today, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2 April to 25 August