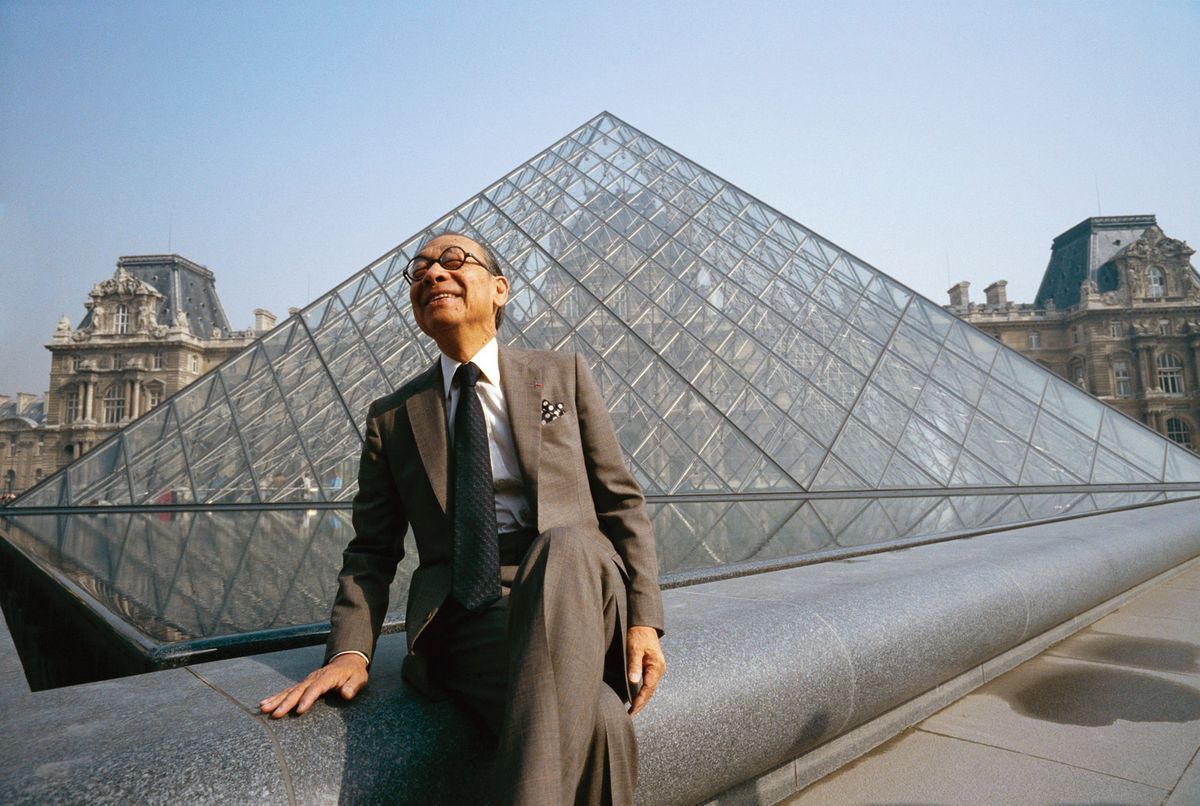

“Poor France.” So wrote Jean Dutourd, a member of the prestigious Académie française, when he heard the announcement of I.M. Pei’s planned landmark entrance to the Louvre. The Chinese-American architect’s glass pyramid was inaugurated by the French president François Mitterrand on 4 March 1989 after years of vitriolic debate not heard in Paris since the early days of the “useless and monstrous” Eiffel Tower. Yet Pei’s bold design has defied the critics, revitalising the Louvre and triggering a worldwide revival of museums and their architecture.

In his memoirs, the head of the project’s curatorial team, Michel Laclotte, insists that political leverage was key to its success. “Pei’s design was Mitterrand’s choice. He refused any international competition and ignored the outcry from the architects in charge of the royal palace,” confirms Jean-René Gaborit, the director of the Louvre’s sculpture department from 1980 to 2004. “All resistance and objections were overcome,” recalls Françoise Mardrus, a member of Laclotte’s team who now leads the Centre Dominique-Vivant Denon, the research centre on the Louvre’s history.

The resistance was fierce. Dutourd published an “appeal for insurrection”. Le Figaro newspaper condemned the pyramid as a “gadget”. A book, written by three unnamed scholars, scathingly denounced “the grand trickery of the Grand Louvre”, referring to Mitterrand’s expansion scheme for the museum.

Pei has said that he has never been so violently attacked. When he presented the project to France’s national commission of historical monuments, Gaborit remembers, his interpreter avoided translating some of the comments before bursting into tears. But Pei certainly understood “It’s not Dallas here!”. L’Amateur d’art magazine wondered “why Mitterrand had to choose a Japanese-American architect [sic], when a French one would never have cut the perspective towards the west of Paris”. Le Monde’s critic André Fermigier blasted this “foreign body, showing such disregard for history”. He quit the newspaper when it published a special supplement devoted to the planned pyramid.

Jacques Delors, Ciriaco de Mita, Helmut Kohl, George Bush, François Mitterrand, Margaret Thatcher, Brian Mulroney and Sosuke Uno. Paris, 14 July 1989. © Ullstein Bild / Roger-Viollet

Wild speculations

Among the wilder speculations, one review claimed that “the acrobatic skills of an Indian tribe imported from Canada” would be needed to wash the 70 triangular and 603 diamond-shaped glass panes. Others fancied that the socialist president had secretly calculated 666 panes for a Masonic pyramid, the cryptic symbol of the devil.

The 22m-high glass monument is in fact cleaned by trained alpinists. Based on a 35m-sided square and supported by a 200-ton steel and aluminium structure, it is surrounded by water basins and three smaller pyramids. Pei was obsessed by light; his main challenge was to find the most transparent, flat glass possible to interact with the sky and the environment, so the views of the courtyard would not be distorted.

On 29 March 1989, the public opening day of the new entrance, “we were thrilled by the new spaces and the circulation towards the galleries and we immediately understood that the game was won”, Mardrus says. “Now that the pyramid is finished,” commented the New York Times, “its sharpest critics seem to have retreated, and it has become fashionable in this city not only to accept the building but even to express genuine enthusiasm for it.”

Pei had been tempted to install a sculpture in the vast entrance hall, but after several unsuccessful trials it became clear that the pyramid itself would be the sculpture, giving ground to the now widespread idea that the first piece of art in a museum is its architecture.

The underground space has had its problems, however, and was restructured between 2014 and 2018 to improve visitor comfort. The Louvre’s current director Jean-Luc Martinez still believes that Pei’s architecture has been key to the museum’s growth and success. More than 10 million people passed through its doors last year, compared with 3.5 million in 1989. “The pyramid is a strong symbol that places the visitor at the heart of the museum,” Martinez says.

Musée de Louvre © Getty Images

World’s biggest museum

Mitterrand’s wider renovation of the Louvre gave it a surface area of 230,000 sq. m—doubling the exhibition space to 50,000 sq. m, partly wrested from the French finance ministry—to make it the “biggest museum in the world”. The total cost of the Grand Louvre development eventually rose to 7bn francs, or €1.5bn today. “The president decided culture should come first, not finance,” Mardrus says. The new facilities included a temporary exhibition gallery, an auditorium, a forensic laboratory, a library, parking for buses, cloakrooms, restaurants and a staff canteen, all next to a shopping mall—the ultimate outrage for some curators. “The construction also led to the most important archeological digs ever in Paris, which were the source of a new national archaeological institute,” Martinez adds.

The architectural transformation paved the way for the “professionalisation” of the museum, Mardrus says. “We were like a family and suddenly we had a small city to manage.” Previously, the Louvre did not have visitor services or communications departments, or even a proper fire department. Security was somewhat neglected and had to be renewed after the spectacular theft of a Corot painting in 1998. Staff were increased from 1,000 to 2,100 today, including 1,200 guards.

The single entrance “played a federalising role”, Mardrus says. Yet, for more than a decade after the pyramid opened, the Louvre had no director, did not control its budget or its staff, and its seven departments were all independent. Those changes would also require a financial revolution, only completed in 2003. “We exposed the museum to the pressure of mass tourism,” Gaborit says, “and we also understood that, from that point on, we would have to find our own money”.