At the tail end of Women’s History Month, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in Washington, DC opens the exhibition Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence (until 5 January 2020), the most comprehensive show ever on the history of the fight for women’s suffrage in the US. “When women succeed, America succeeds,” said Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the House, who spoke at Thursday night’s opening ceremony with former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the California congresswoman Doris Matsui—all decked out in “Suffragette White”.

“Because it’s a women’s movement, I believe it has been written out of history at large,” says Kate Clarke Lemay, who organised the show, which was initially due to open at the beginning of March, but was slightly delayed due to the partial government shutdown. Lemay is also the coordinating curator of the on-going Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, and says that women’s suffrage “is one of the longest reform movements in American history. It’s hard to pin down one narrative history.”

To begin to tackle this vast subject, the show of around 125 objects is organised into six chronological and thematic sections, from “Radical Women: 1832-1869” to “The Nineteenth Amendment and Its Legacy”, reaching forward to the signing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Each section has own intimate gallery space, with three rooms on each side of a long hallway. “Because the movement itself stemmed from the 19th century, I’m really happy to have what feels like a 19th-century space,” Lemay says.

The show delves into the complexities of the fight for women’s right to vote, including racism in the movement and the exclusion of African American women like Ida B. Wells-Barnett by major white suffragists such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who held white supremacist views and aligned themselves with men such as the pro-slavery railroad magnate George Train for support. It also extends beyond the granting of women’s suffrage. “It’s not like the 19th amendment in 1920 wrapped up women’s voting rights with a pretty bow,” Lemay says.

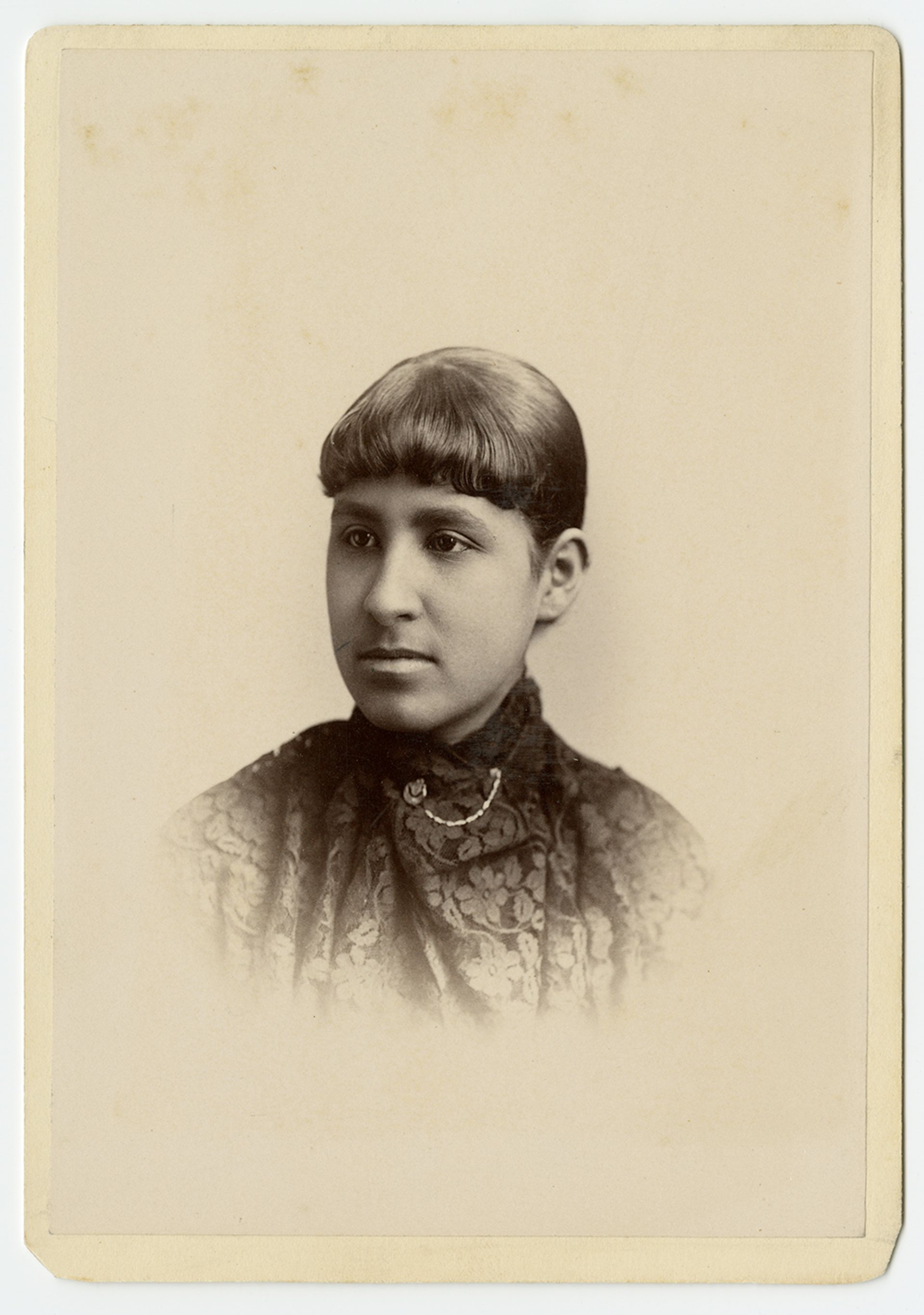

H.M. Platt, Calling card portrait of Mary E. Church Terrell as a college student (1884) Courtesy of the Oberlin College Archives

Among Lemay’s favourite objects on display are calling-card portraits from Oberlin College in Ohio of the African American suffragists Ida Gibbs Hunt, Anna J. Cooper and Mary Church Terrell as students. “I wanted to find images of these women while they were being radicalised as young women,” Lemay says. For younger visitors, “Elizabeth Cady Stanton doesn’t look really approachable”, she adds. “But a young Mary Church Terrell does.”

Biography is a major theme in the Votes for Women, Lemay says, and there is a second portrait on view of Terrell, an activist and educator who co-founded the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896, on loan from Howard University in Washington. The photograph shows Terrell with her young daughter Phyllis around 1901, showing that “this woman who did so much for the suffrage movement was also a mother, she’s a complete person” beyond her role in the movement, Lemay says.