Jochen Volz, the director of the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, is adamant that Ernesto Neto’s art practice is not just centred on spectacle. The Brazilian artist is known for his large-scale, immersive multi-sensory installations incorporating materials and elements such as polyamide stockings, crocheted nets and spices and herbs. A selection of these, including Velejando entre Nós (2012-13), will feature in a 60-piece retrospective of the Rio de Janeiro-born artist’s work at the Pinacoteca: Sopro [Blow] (until 15 July).

“The exhibition has not been developed around the notion of the spectacle, but rather in favour of telling the story of Neto’s art-making,” Volz says. For example, with the series of works entitled Naves (Ships) from the mid-1990s, Neto created for the first time expansive installations using materials such as lycra, styrofoam, cloves and sand, he says.

“Visitors are invited to take off their shoes and enter the interior of the [Naves] sculptures suspended from the ceiling through a slot in a large organic vault. The sheer presence of the viewer within the work leads to its deformation. The observers become part of the sculpture, their bodies are inscribed in a comprehensive organism,” Volz says.

Ernesto Neto's Oxalá (2018) © Pat Kilgore

Neto has expanded the principles of structure and made us look at gravity and equilibrium in a new way, the exhibition organisers claim. “Gravity and balance, solidity and opacity, texture, colour and light, symbolism and abstraction are the anchors of his practice, a continuous exercise about the individual and collective body, about equilibrium and community building,” Volz says.

Key works on show include the early piece Copulônia (1989-2009), a work comprising polyamide and lead spheres, some of them interconnecting with suspended structures. “It conveys the idea of population, family, collective body and symbiotic coexistence,” Neto says. TomBorTom (2012) prompts the viewer to be playful and hit a ball against a basket hanging in a net from the ceiling. Oxalá (2018) takes interaction a step further, inviting spectators to don crocheted headbands attached to a hanging wall net.

The show also explores Neto’s close links to the indigenous community of Huni Kuin (Kaxinawá), an ethnic group of around 7,500 people that inhabits an area on the border of Brazil and Peru. At this fraught political moment in Brazil's history following the rise of the far-right, showing Neto’s ancestry-focused works is timely.

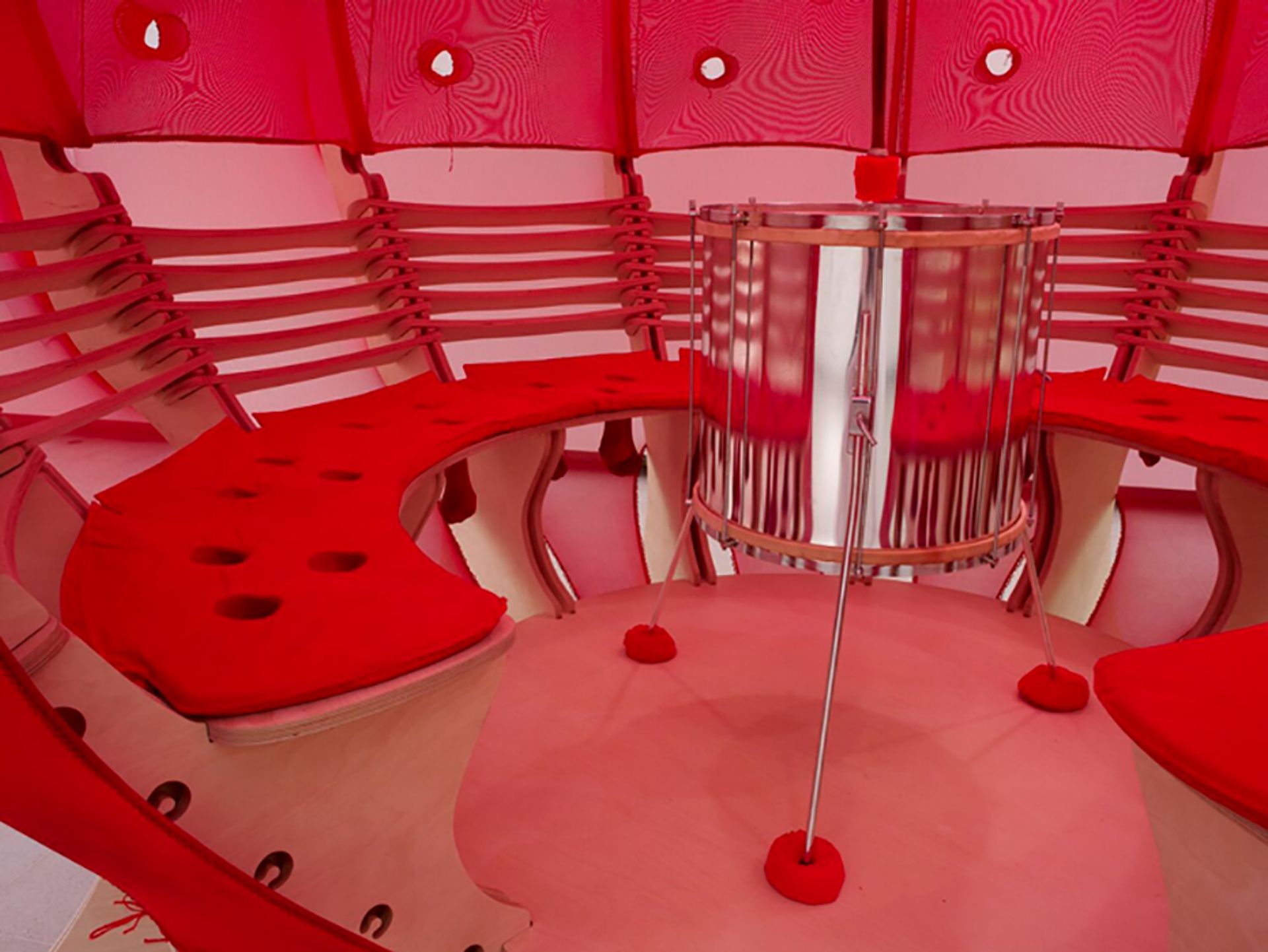

Ernesto Neto's Circleprototemple...!, (2010) © Eduardo Ortega

Volz points out that artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian were just as interested in evolutionary theories and atomic physics as they were in supernatural phenomena and spiritualist movements such as theosophy.

“For these artists, there was no contradiction between these distinct ways of understanding the world. The same can be said about Ernesto Neto’s production, and especially his research into artists, shamans and political leaders of the Huni Kuin nation,” he says. Neto began working with the Huni Kuin community in 2013.

A room dedicated to the Huni Kuin will house an installation comprising drawings, craft-nets, and photographs of community villages produced by the artist and members of the group. “The idea is to bring the tribe atmosphere into the museum,” a gallery spokeswoman says. All of the works are on loan from Brazilian public or private collections, or owned by the artist.

The show is sponsored by Banco Bradesco, Mattos Filho Advogados, Iguatemi São Paulo and Havaianas.

• Ernesto Neto: Sopro [Blow], Pinacoteca de São Paulo, São Paulo, 30 March-15 July