How do you create a new national museum of note without a stellar collection? And how do you ensure that it serves as both a local museum for everyone, and as a powerful statement of nationhood that will help transform Qatar into an Arab capital of culture? The National Museum of Qatar, which opens its doors to the public on 28 March, reveals that it has found some answers to what could have been deemed difficult questions at best, and judged serious shortcomings at worst.

The prime vehicle is, of course, its breath-taking Jean Nouvel-designed building, which leaves most state-of-the-art museums in the shade. The French architect has been involved in every aspect of the endeavour, including the detailed scenography of the gallery interiors themselves.

The intellectual conceit of the building is stunningly simple—a “desert rose”, a mineral formation found in the deserts of the Gulf, which has inspired an organic system of interlocking disks and the subtle unified tonality. Yet the acrobatics of the engineering is anything but straightforward. There are 539 disks in all, with 76,000 patterned cladding elements.

The Palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al-Thani is enveloped by the new National Museum of Qatar © Iwan Baan

Inside there are 11 interlined galleries, forming a loop of 1.5 km for the visitor to perambulate. Inside, everything undulates, nothing is straight, the walls curve inwards and outwards, the ceilings rise and dip, patterns and spots unify ceilings and floors “like an animal identity”, and there are surprises at every turn.

The architecture enfolds the renovated Palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al-Thani, which—by a clever sleight of hand—becomes one of the most prized objects in the museum as well as a core element of the architecture. In its courtyard, one can briefly bask in the glare of sunlight, before continuing the elliptical journey, moving as if part of a nomadic tribe.

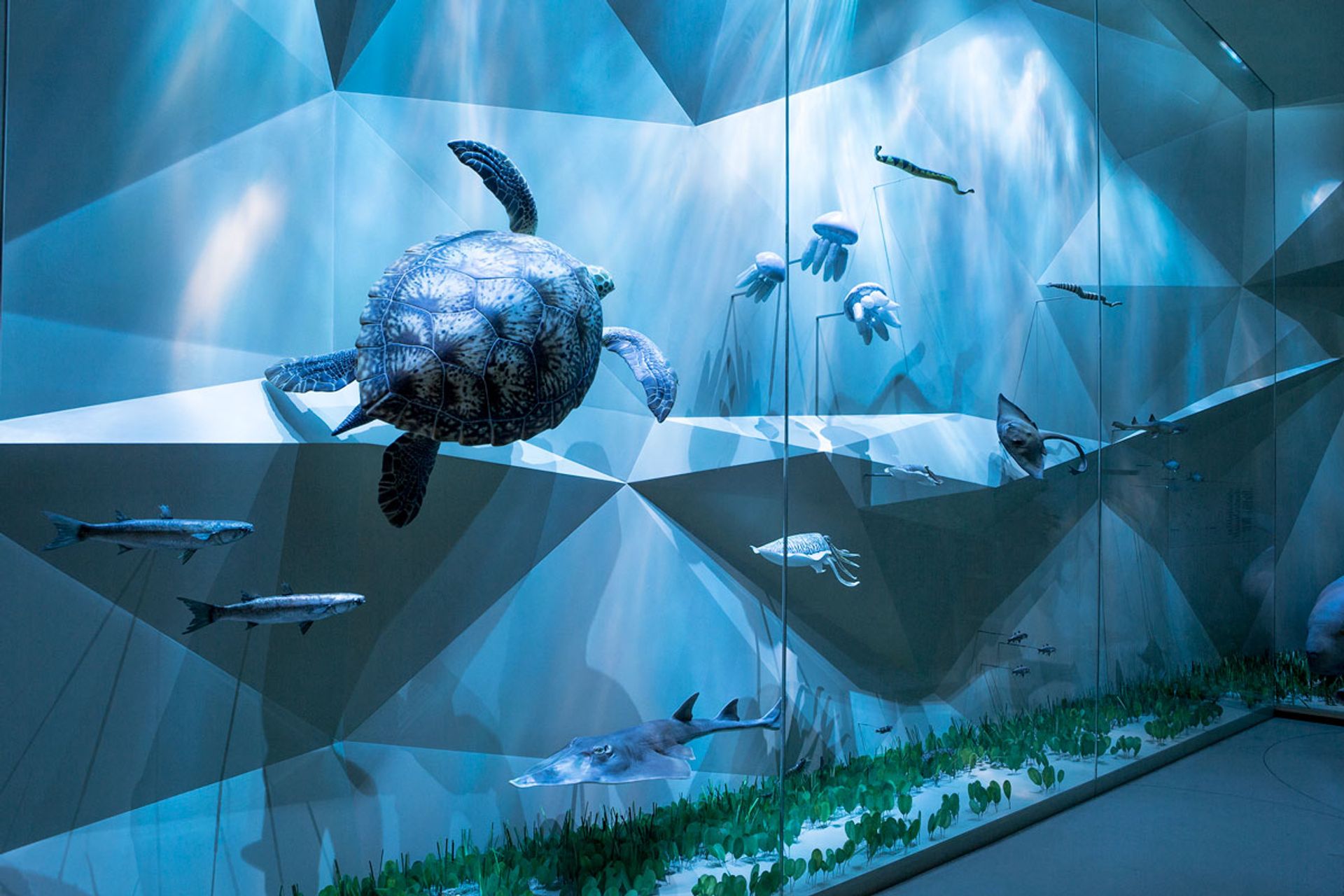

Aquatic display in the Natural Environments gallery at the new National Museum of Qatar © Danica Kus

The museum draws on every aspect of modern museography, to create what are primarily immersive displays and an engaging learning experience. Real artefacts in vitrines are magically suspended in the air, in innovative displays that create an effective dialogue with the bespoke art films and oral histories surrounding them.

A powerful temporary exhibition on Making Doha 1950-2030, jointly curated by Rem Koolhaas, Samir Bantal and Fatma Al Sahlawi, provides some intellectual heft and reveals how vitally important it is for Qatar to preserve its history given the intense speed of social, political and architectural development. This is a 21st-century museum, which emphasises the 3D experience in all its manifestations, but it also manages to have heart and soul.