"In 1971, Chris Burden disappeared for three days without a trace," relates the description for a forthcoming exhibition at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. But Burden was not the first, or the last, artist to go missing and artists can become “lost” in many different ways.

Perhaps the most prevalent is an artist who is lost to popular imagination—and therefore to memory and posterity—because they were never widely recognised in the first place. This theme has grown to prominence with the release of the Netflix documentary Struggle: The Life and Lost Art of Szukalski, financed by Leonardo Di Caprio and his father, to tell the story of the search for a Polish artist whose work they admire. But Szukalski achieved enough success and notoriety that the DiCaprio family were fans. What about artists who barely pierced beyond the sightlines of their home regions, but who may be wonderful and talented in a way that would garner international renown, had the PR pieces fallen into place? In the Internet era, it is much easier for anyone, with or without talent, to promote their creations. But there is such a tidal wave of information online that it is perhaps harder than ever to separate the wheat from the chaff and to find someone who is truly resonant.

Consider the subject of my doctoral dissertation, the Slovenian Modernist mystic architect, Jože Plečnik. He is the darling of architectural historians and savvy critics, but is largely unknown to the wider public. It was not until last November, when Kanye West tweeted about him, after having encountered his work in an exhibition on Yugoslav concrete architecture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, that the social media cosmos suddenly became aware of his name.

Similarly, a show on the brilliant Slovenian Impressionist painter, Ivana Kobilica, at the National Gallery in Ljubljana reveals an artist every bit the equal, technically, of the French Impressionists, but her geographic location, hidden on the “sunny side of Alps”, means that almost no one outside of Slovenia knows her name or has seen her work.

In the tiny town I call home, Kamnik, Slovenia, I’ve encountered several artists of world-class talent who have never extended beyond the region. Not long ago, a friend brought me to an ordinary apartment building in town and showed me a spare bedroom packed with astonishing creations by a local artist named Tone Žnidaršič, who died in 2007. He handmade elaborate polyhedrons, like hollow multi-faceted spheres, mathematically perfect and cut out of cardboard, all without using computers. Some were cast in bronze, but most were of delicate paper, hanging from the ceiling of this random, “invisible” private bedroom in a building I had walked past dozens of times without thinking twice about.

The Slovenian artist Tone Žnidaršič, who died in 2007, handmade elaborate polyhedrons, like hollow multi-faceted spheres, mathematically perfect and cut out of cardboard, all without using computers

The friend who had invited me is another Kamnik artist, Dušan Sterle, who is a bit of a local legend: he looks like Santa Claus, if Santa Claus were found hanging around outside of bars, chain-smoking cigarettes and drinking espresso. I had met him casually before, but it was not until a mutual friend brought me to his apartment studio that I realized what a hidden gem was in our midst. His home is covered, floor to ceiling, in paintings in a variety of styles, and in the attic of his building there are hundreds more of his paintings, stacked up in neat lines. He has never bothered to self-promote and is quite relaxed about his very local output. He’s not interested in galleries or managers or press. There is much to be said for being content with what falls before you, the Tao of Art, in a time when artists tend to focus more on self-promotion than on their creative output. But this approach also means that, unless you happen to stumble on an artist like Sterle, as I did, you might never encounter his work.

Another category of lost artists are those who were stolen by death before their time. Carel Fabritius was made famous in Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, and was an artist of the highest level, but suffered a double tragedy. He died on 12 October 1654, aged 32, in the same gunpowder accident that destroyed almost all of his works. But at least Fabritius had achieved enough recognition that his name and remaining output would be remembered, like other artists who died too young: Giorgione at 32 years old, Schiele at 28, Raphael at 27. My neighbour in Kamnik is a local gallerist who introduced me to the work of a friend of hers, Barbara Ravnikar, who was similarly lost to an early death. As well as being a fine graphic artist and painter, Ravnikar spent years studying mosaic production in Germany and had found work as a mosaicist at the Vatican. She appeared to be on the cusp of notoriety when she passed away, aged 53.

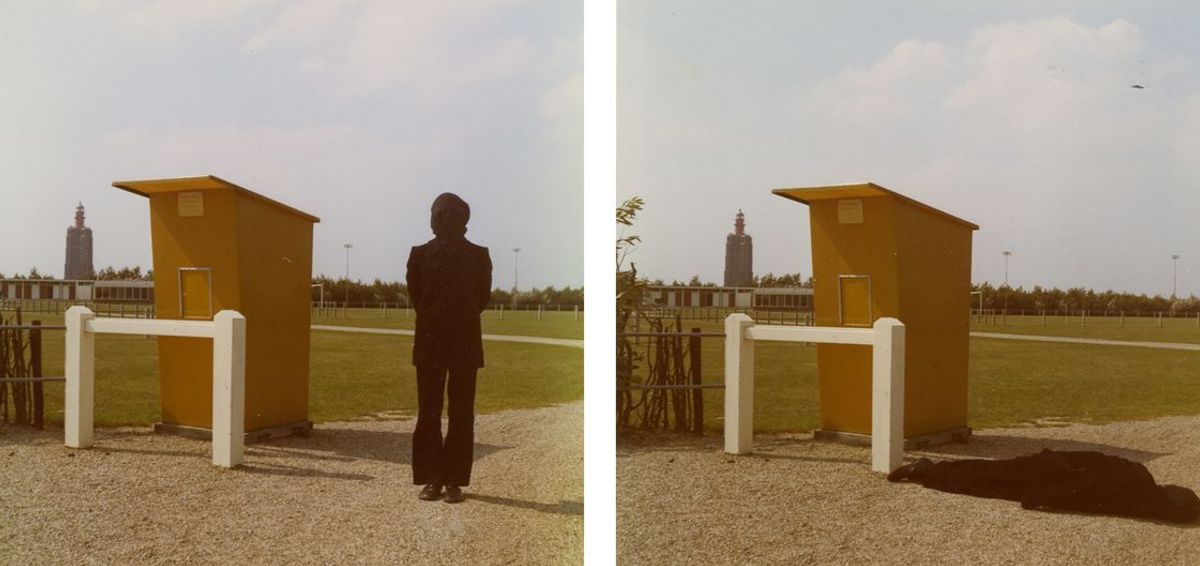

There is one other way that an artist can be lost—like Burden, by their own devising. The Dutch conceptual artist Bas Jan Ader spent most of his short life in the US, working as a photographer and performance artist in Los Angeles. On 9 July 1975, he set off alone from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in a tiny sailboat, aiming to cross the Atlantic from New England to England. The journey was to be a performance, called In Search of the Miraculous, and it would be his last. His vessel, a 4-metre Guppy 13, which he had named Ocean Wave, was not intended for transoceanic voyages and was the smallest craft ever used in an attempt to cross the Atlantic. The performance began with a choir singing sea shanties around a piano in the gallery of his Los Angeles dealer, and was to end with another sing-along at Falmouth, in southern England, about two and a half months later.

Bas Jan Ader, still from the launch of the Ocean Wave, Chatham Harbor, Chatham, Massachusetts, June 1975, colour photograph © The Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen, 2018 / The Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles

After three weeks, radio contact with the Ader ceased. Ten months later, on 18 April 1976, Ocean Wave was spotted 240 kilometres off the coast of Ireland, bobbing vertically in the waves—empty. The boat had previously been seen 97 kilometres off the New England coast and again passing the Azores, but those were the only two sightings. It was recovered by a Spanish fishing boat and towed to the town of Coruña, from where it was stolen sometime between 18 May and 6 June 1976.

Ader is assumed to have drowned. Did he intend this voyage to be suicide-as-performance-art? Or was he convinced he could make the crossing—ill-advised though it was in such a small vessel and without any help—and was simply overcome by the sea? Or did he, just maybe, deliberately create the most literal work of “lost” art?