The experimental film-maker and artist Barbara Hammer, a pioneer of lesbian film, has died aged 79 after a 13-year battle with ovarian cancer. “It has been the goal of my life to put a lesbian lifestyle on the screen,” Hammer said in a statement for the launch of an annual $5,000 grant she launched to support experimental artists and film-makers who identify as lesbian. “Why? Because when I started, I couldn’t find any!”

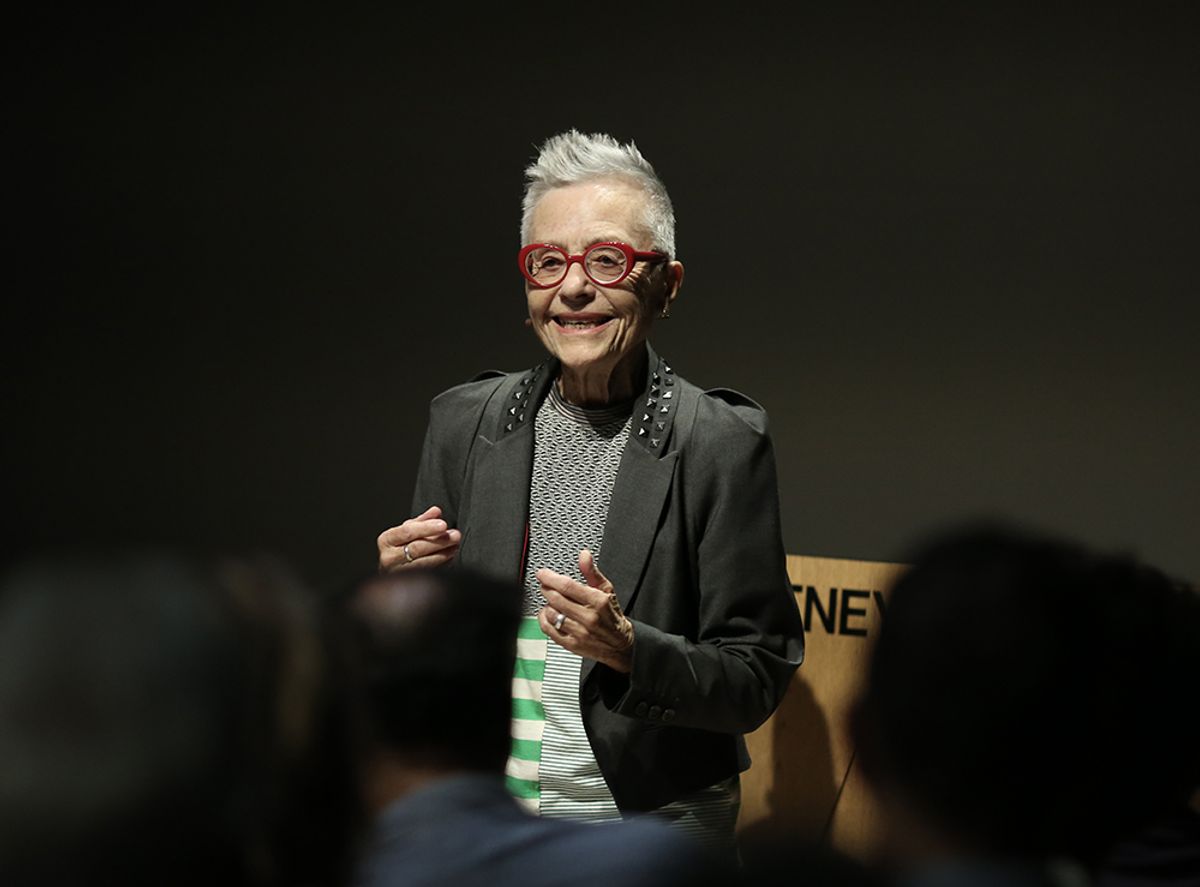

Hammer, born in Hollywood in 1939, earned degrees in psychology and English in the 1960s before studying film at San Francisco State University. In 1974, she made her breakthrough work, Dyketactics, in which four rolls of film are layered on top of each other to create a joyful dream-like two-minute scene of women frolicking with each other in nature. “I had great pleasure in making Dyketactics,” she said this past October at the third and final version of her performative lecture, The Art of Dying or (Palliative Art Making in an Age of Anxiety), at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. She described the process of cutting. “We know the pleasure that comes from the creative process, whether it’s defiance of restrictive social mores, or deliverance through ecstatic expression,” she said. “Pleasure yourself in the joy of making. When you have an idea, follow it with gusto and pleasure, having as much fun as possible along the way.”

Hammer’s first feature film was the experimental documentary Nitrate Kisses (1992), which won the Polar Bear Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 1993. She has had solo exhibitions at institutions including the Jeu de Paume in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and Tate Modern in London and the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York. She also showed in the 1985, 1989 and 1993 iterations of the Whitney Biennial. Hammer’s work is in international collections including MoMA, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne.

Her work Evidentiary Bodies premiered at the 2018 Berlin International Film Festival, was completed with the assistance of Paul Hill through a residency at the Wexner Center for the Arts. This project was part of a grant to complete five unfinished works from the 1970s-90s with the help of other film-makers. “She wasn’t well enough to finish them,” Hammer’s spouse Florrie Burke said in a joint “exit interview” in the New Yorker in February. “And she had an idea: What if I choose a film-maker that I think would be appropriate for each of the five?” The project is due to be completed this summer.

Hammer became an activist for medical aid in dying during the course of her illness and challenged taboos around death. In The Art of Dying or (Palliative Art Making in an Age of Anxiety) at the Whitney, Hammer said: “We in the art world, all of us—artists, curators, administrators, art lovers alike—are avoiding one of the most potent subjects we can address… Guess what? The art of dying is the same as the art of living.”

“I would be so grateful to be able to manage my own death by choosing the time and the person I’d like to have with me, so that I can die in comfort and with compassion,” she wrote in an op-ed published in the New York Daily News last month. “I am not talking about suicide. My love of life is as strong today as it has ever been. But I am dying. That is a fact. And it will not change.”