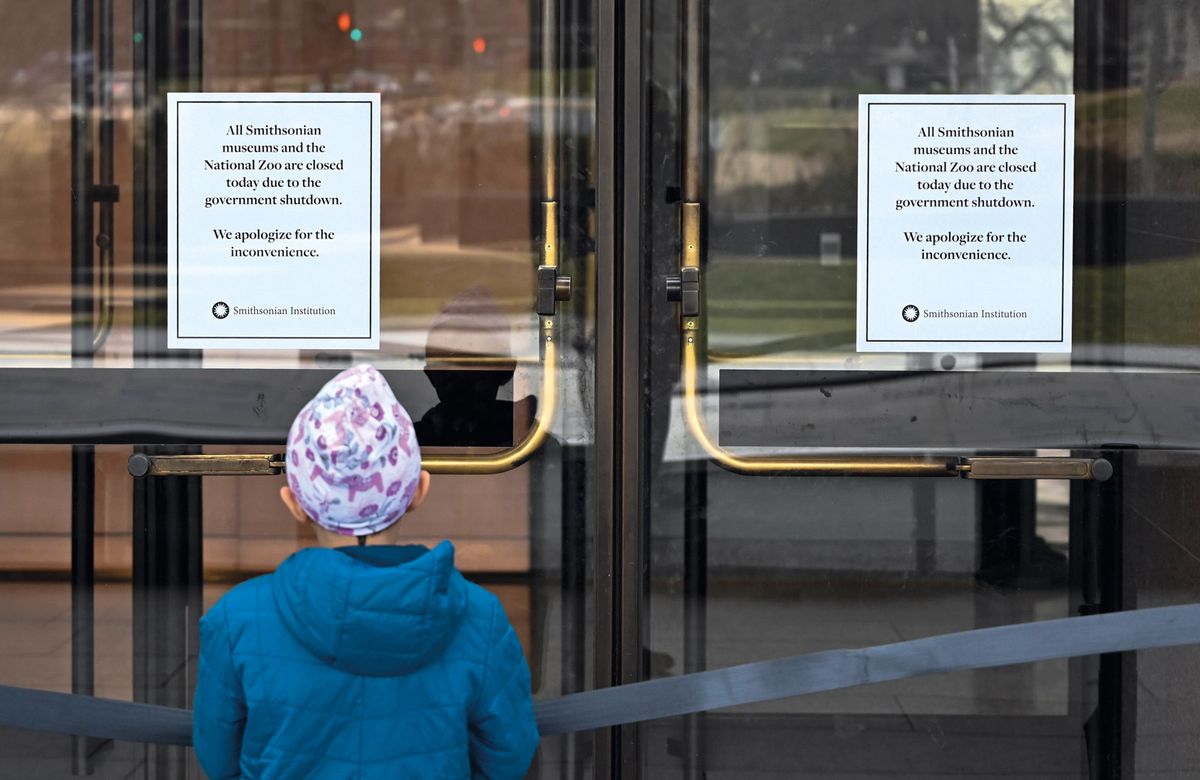

As the prospect of a second US government shutdown loomed in February, federally-funded museums scrambled to get back on track after their longest closure ever. The 35-day partial government shutdown from 22 December until 25 January not only left major venues in Washington, DC, and New York shuttered for almost all of January, but also disrupted finances, operations and exhibition schedules, with effects to last for months and even years in some cases, and millions of dollars of revenue lost.

Although leftover funds from the 2018 fiscal year enabled all federal museums to stay open for 11 days during the shutdown, coinciding with the busy holiday period, Smithsonian Institution museums and the National Gallery of Art (NGA) went dark for 27 days and 26 days respectively, reopening only on 29 January.

In that time, the Smithsonian—19 museums including the Cooper Hewitt design museum in New York and the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) and National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, along with the National Zoo—lost an estimated 1 million visitors, according to a spokeswoman. The NGA lost an estimated 334,000 visitors, a spokeswoman says, and 11,700 schoolchildren, senior citizens and others missed out on programmes.

“I think that’s the biggest loss—the public-facing piece,” says Melissa Chiu, the director of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

The NPG’s director Kim Sajet laments that the public will miss nearly a month of its show Votes for Women: a Portrait of Persistence, which had to be postponed (see above right). She estimates that the museum lost 150,000 to 180,000 visitors during the shutdown and says that visits for 37 school groups were cancelled.

The public also missed out on the remaining weeks of several noteworthy temporary exhibitions that ended as scheduled during the shutdown, including the travelling Rachel Whiteread show at the NGA, the largest ever dedicated to the UK sculptor’s work. The museum’s show on the US photographer Gordon Parks—“more than three years in the making”—could not be extended past its 18 February end, so was closed to the public for nearly a month of its 15-week run, the spokeswoman says. Other shows were extended: the Hirshhorn added nearly three months to the exhibition Charline von Heyl: Snake Eyes (until 21 April).

The NGA has revised its exhibition schedule, including a two-week delay for the opening of its biggest spring show, Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice, the first major survey on the artist in North America, now due to open on 24 March. The domino effect has even pushed a mid-2020 show on the photographer Larry Fink back by seven weeks.

The shutdown also furloughed most of the 140 staff of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the federal grantmaking agency that manages an indemnity programme to support the cost of insuring temporary exhibitions. However, a spokeswoman says that “previously approved indemnity coverage remained in effect and co-ordination of the programme resumed as soon as the furlough ended”.

Although national museums (except the Cooper Hewitt) offer free entry, the Smithsonian lost an estimated $3.4m in gross revenue from its gift shops, concessions and IMAX film screenings—which “can never be gained back, of course,” the spokeswoman says. The NGA lost an estimated $1.2m in gross revenue from its shops, restaurants and ice rink, its spokeswoman says.

The shutdown’s impact on workers at federal museums depended on the bodies that pay them. The NGA’s staff is 84% federally-funded, compared with only around two-thirds of Smithsonian staff, with salaries for the remaining third coming from trusts and private sources. Some 2,000 trust-funded Smithsonian staff were thus able to work during the shutdown.

Of the Smithsonian’s 4,000 federal workers, all but 800 were furloughed; the majority of those who continued working were involved with operations at the zoo, according to the spokeswoman. The Smithsonian Institution’s Office of Planning, Management and Budget released a contingency plan ahead of the shutdown outlining duties that would exempt employees from furlough, such as responsibility “for the care, custody and protection of the National Collections”—which includes the zoo animals—or ensuring safety of people on the institution’s property.

While Congress authorised back pay for all furloughed federal workers, employees of outside contractors, such as some security guards and food service workers, were not guaranteed the same. Allied Universal, a private security guard contractor, says it “provided vacation buyback for accrued time and furlough letters to help officers who needed assistance with bills” and helped employees find “alternative work until they could return to their government posts”.

The shutdown also dealt a blow to researchers who were unable to use the libraries or collections, said a furloughed Smithsonian employee who spoke anonymously, adding: “When you have a fellowship to do research… if you lose a whole month, that’s serious.”

The restrictions extended to the virtual world, as furloughed employees were not permitted to check their government email. Sajet made a Facebook group to keep her NPG staff abreast of developments amid falling morale.

“The staff are really kind of at a loss when you can’t complete your mission,” she says. “A museum is not a museum unless it has the public there.”

Before a new spending bill was signed on 15 February, Sajet, still facing the prospect of another shutdown, commented: “I think we will probably just do what we’ve done before—sit back and [ask ourselves] what do we have to do, what do we postpone and what do we cancel?”

Better late than never: ‘herstory’ of US suffrage

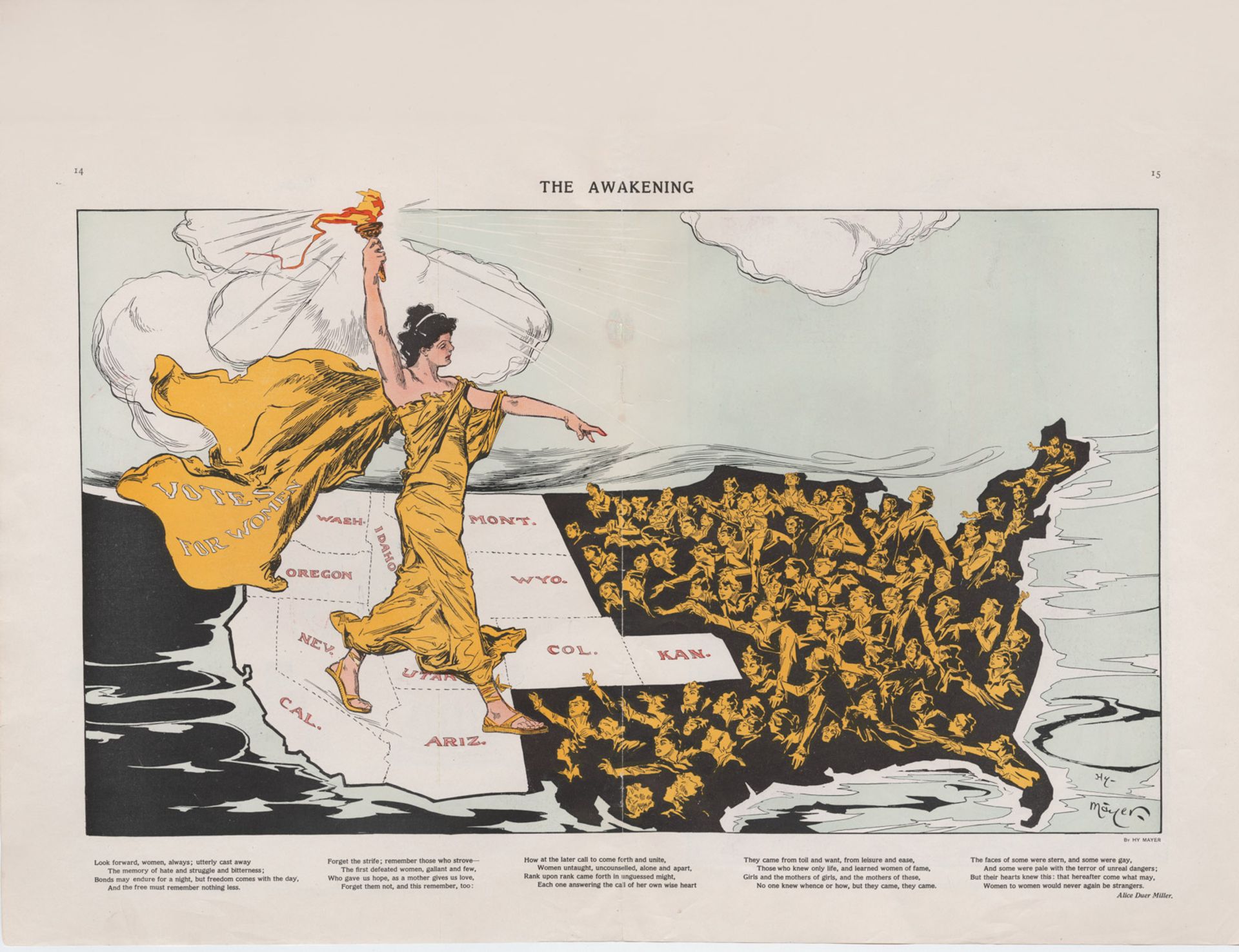

Henry Mayer’s cartoon The Awakening (1915) will be among 120 objects tracing the fight for women’s suffrage at the National Portrait Gallery © Cornell University; courtesy of the NPG

Delayed by the shutdown, the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Votes for Women: a Portrait of Persistence (29 March-5 January 2020) will now open at the end, rather than the beginning, of Women’s History Month this March.

The show aims to present a comprehensive picture of “one of the longest reform movements in US history”, says the curator, Kate Clarke Lemay, including the place of black women within the suffrage campaign, and their struggle for wider citizenship rights. With around 120 objects from 1832 to 1965, it extends beyond the signing of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote in 1920.

It is a major part of the Smithsonian’s five-year women’s history initiative Because of Her Story, co-ordinated by Lemay, which was launched with a $2m grant from Congress in 2018 to support exhibitions, scholarship and other programmes.

-V.S.B.