An Austrian museum is coming to terms with the tainted legacy of its first director and founding collector, Wolfgang Gurlitt, a dealer in Nazi-looted art. He was a cousin of Hildebrand Gurlitt, whose hoard of 1,500 works was seized by German officials in 2012 in the Munich apartment of his son Cornelius, an elderly recluse. More than 20 years after it began provenance research on Wolfgang’s collection, the Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz is now preparing an exhibition that will explore his equally fascinating story for the first time.

Wolfgang and Hildebrand were often at loggerheads but they had much in common. Both were art dealers who worked for Adolf Hitler’s regime, and both were a quarter Jewish. Like his cousin, Wolfgang bought works that had been looted from Jews during the Third Reich or were sold at knock-down prices by Jews seeking to flee Nazi Germany. He, too, managed to rehabilitate himself after the Second World War.

In 1946, Wolfgang Gurlitt gained Austrian citizenship and became director of what was then called the Neue Galerie in Linz. He sold 88 paintings and 33 works on paper to the city in 1953—a step that finally liberated him from the financial difficulties which plagued him for most of his career. He also insisted that the museum be renamed the Neue Galerie der Stadt Linz, Wolfgang- Gurlitt-Museum; the city agreed.

“He demanded a lot,” says Elisabeth Nowak-Thaller, the Lentos Kunstmuseum’s deputy director and head of collections, who is organising the exhibition due to open on 4 October. “He always saw himself as a patron, but in fact he sold the city his collection.” In 2020, the show will travel to the Museum im Kulturspeicher in Würzburg, which bought around 130 works from Gurlitt.

There had been doubts about the provenance of his art since the 1950s, and some claims. In 1998, the year that Austria passed a restitution law, the head of Linz’s historical archives wrote a report on Gurlitt’s collection and the museum established its own provenance research group. It has since restituted 12 of the works to the heirs of the original owners, including Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Ria Munk III (1917-18) and an Egon Schiele landscape.

“Regardless of whether there is a claim, the paintings in the Gurlitt collection are being systematically researched,” Nowak-Thaller stresses. “The provenance of many of them has been cleared up. At the moment there are no claims nor any works that are strongly suspected of being looted.”

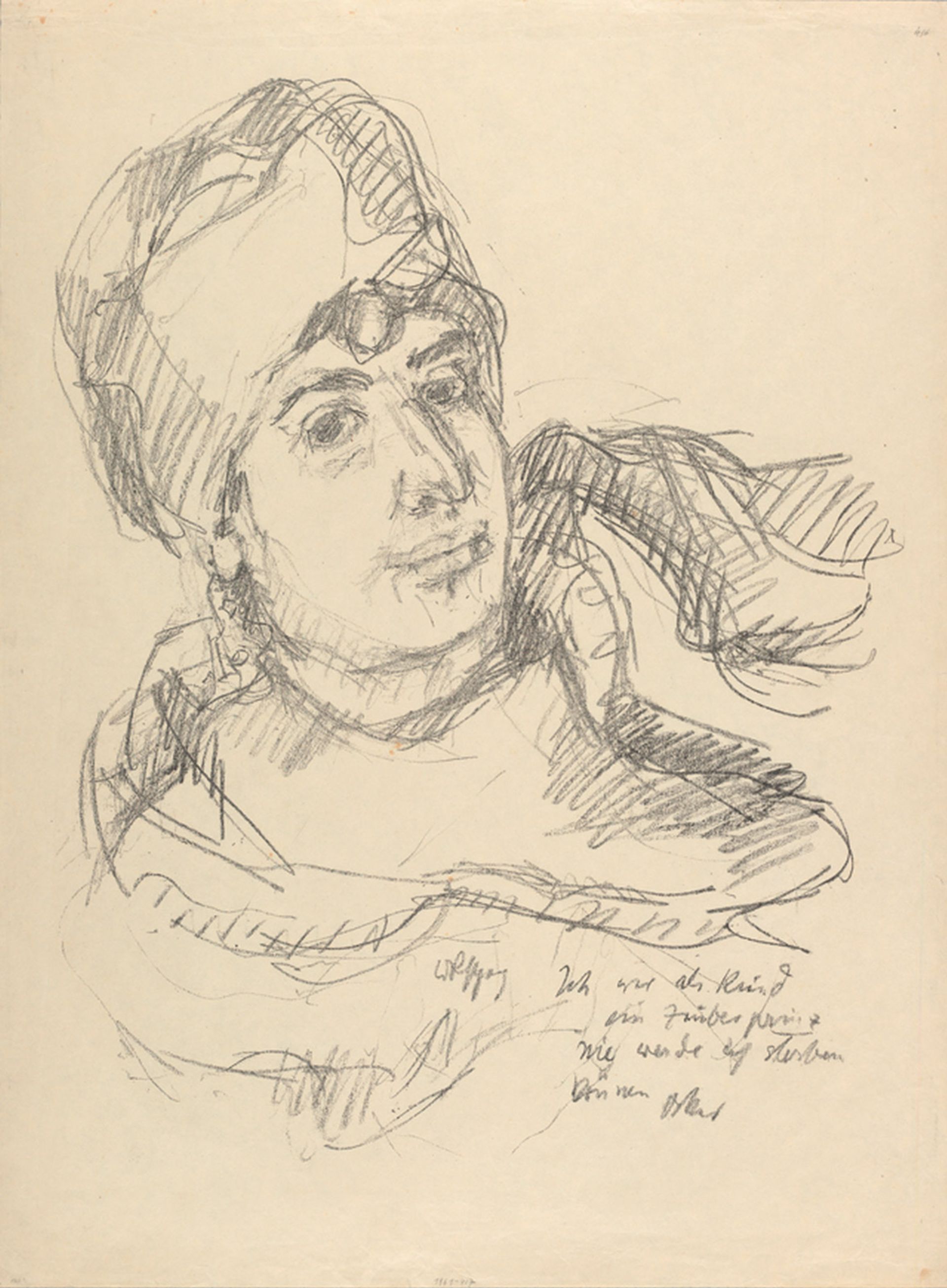

Oscar Kokoschka’s portrait of Gurlitt, Zauberprinz (1922) © Fondation Oskar Kokoschka/VBK, Vienna

Until now, art historians have largely concentrated on Wolfgang’s collection; far less is known about this flamboyant character, who courted controversy during his lifetime as well as after his death. The Lentos Kunstmuseum’s exhibition is “long overdue”, Nowak-Thaller says, in part because she served for a stint as its interim director and needed more time for research. The show was originally planned to open before the touring exhibition of Cornelius Gurlitt’s art hoard in Bonn, Bern and Berlin, which closed in January.

The Linz show is titled Zauberprinz, or “fairytale prince”, after a 1922 drawing of Wolfgang Gurlitt by Oskar Kokoschka. Wolfgang took over his father’s Berlin gallery after the First World War and was one of the first German dealers to sell works by Modern artists such as Edvard Munch, Henri Matisse and Schiele. He counted Kokoschka and Max Pechstein as friends, commissioning the latter to design stained-glass windows for his extravagant Berlin apartment.

His unconventional lifestyle must also have raised some eyebrows. He moved from Berlin to the Austrian village of Bad Aussee in 1940 with his wife and children, but also with his ex-wife and his Jewish mistress and business partner Lilly Agoston. “Perhaps it’s not surprising Kokoschka portrayed him as a kind of pasha in a turban,” Nowak-Thaller says.

Like his cousin, Wolfgang entered the circle of dealers who worked for the Nazis by selling art that the party confiscated as “degenerate”—the Modern art he loved. He later acquired works for the Linz Special Commission, the team behind Hitler’s unrealised Führermuseum in Linz, but never achieved the same level of activity as Hildebrand.

Wolfgang was also “very confrontational”, Nowak-Thaller says, constantly burdened by debt and often embroiled in lawsuits, including against Hildebrand’s side of the family. As director of the Neue Galerie, he protested whenever city literature referred to the museum without his name, and there were disputes over his expenses. In 1950, he complained that he had not been appointed to manage the city’s new art academy.

He staged more than 100 exhibitions in Linz. His Kokoschka show in 1951 was the first in Austria since 1937. An anti-war exhibition under the motto “Never Again!” was provocative for 1952. But most of the exhibitions showed art that was for sale, Nowak-Thaller says. Gurlitt effectively used the museum to host his dealership, even after he opened a new gallery in Munich in 1950.

The city eventually tired of this conflict of interest, firing him in 1956. But when Linz decided to eliminate his name from the museum’s title in 1960, Gurlitt sued—and won. The museum was stuck with it until 2001, 36 years after his death. It finally became the Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz with the move to a brand-new building in 2003.