The art historian and Picasso biographer John Richardson died aged 95 at home in New York this morning. Just before he died, we visited him in his downtown New York apartment to discuss his new book, which focuses on the places in which he has lived and the objects he has collected across his long and eventful life.

Over his long life, John Richardson has had a front row seat for a huge span of history. He has known art world luminaries such as Peggy Guggenheim, Anthony Blunt, Andy Warhol and, of course, Pablo Picasso, about who he has written the definitive multi-volume biography. The long-awaited fourth and final volume of A Life of Picasso is now complete and set for release later in the year, yet Richardson shows no signs whatsoever of slowing down, even if macular degeneration is impacting his sight. In his newest book John Richardson: At Home, published by Rizzoli, he opens the doors to the places he has lived and his vast and eclectic personal collection. The book is packed with sumptuous photographs of those interiors and the objects within them. Richardson has said: “They represent the story of my life.”

The book takes us right back to his childhood home in London—Richardson’s father was quartermaster general in the Boer War and founded the Army and Navy Stores. He was knighted by King Edward VII; in 2012, Edward’s great granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth II, knighted Richardson himself. The book takes us to the Château de Castille near Avignon, owned by Douglas Cooper, the art historian who was Richardson’s partner in the 1950s, and filled with the Cubist masterpieces Cooper had collected. Picasso and Jean Cocteau were among the regular visitors to the château. Other chapters are devoted to Richardson’s quarters in London’s Albany—the 19th-century estate next to the Royal Academy—and his two apartments in New York, as well as his country house in Connecticut.

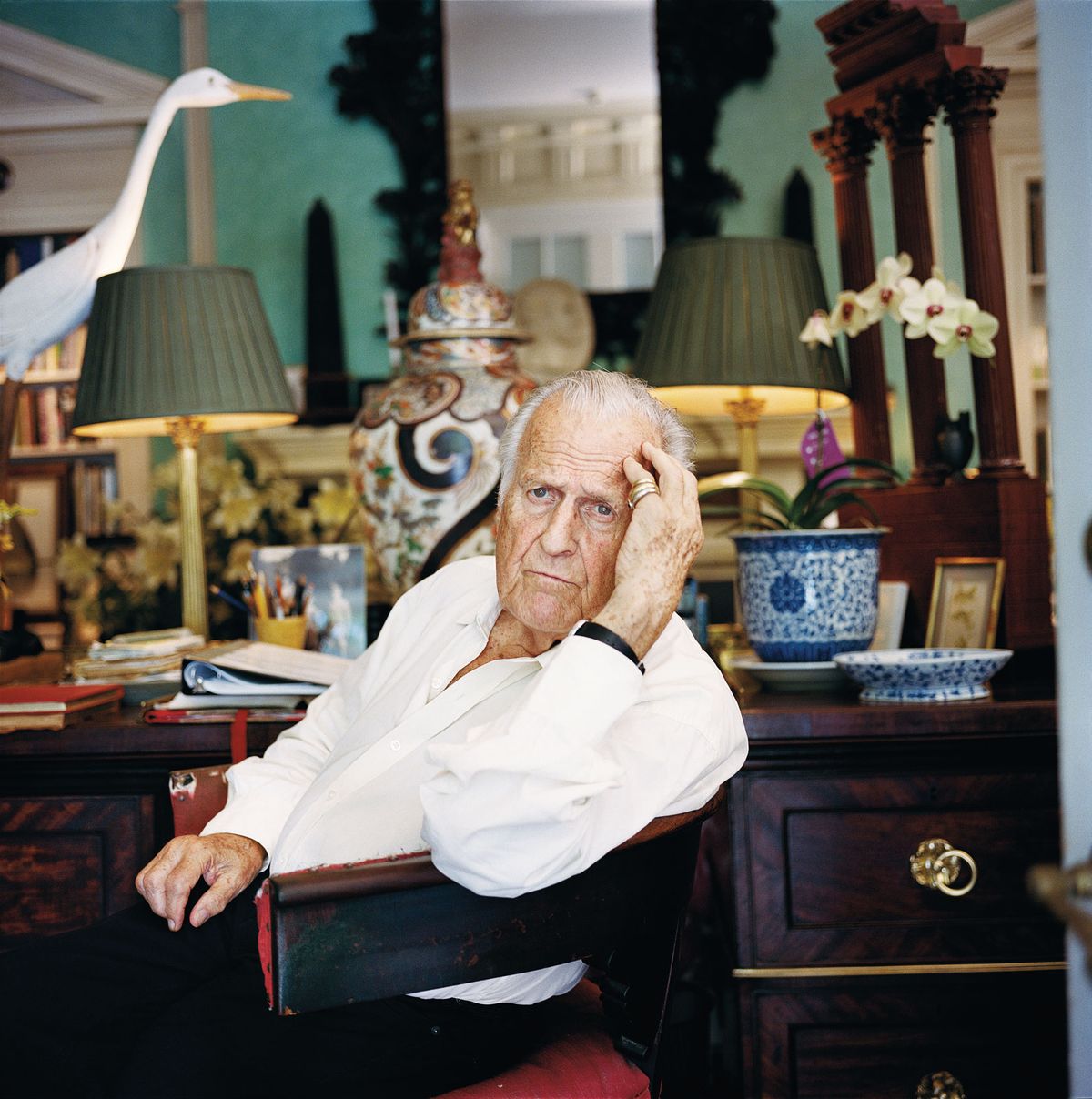

I visited Richardson in his cavernous downtown Fifth Avenue loft, which had been a former dance studio. It has been his home for close to a quarter century—Richardson says his uptown “lady friends” were horrified that he would decamp to such “unsavoury part of town”. It is as rich and complex and surprising as Richardson himself, an aerie comprising some 5,000 sq feet, or roughly the size of five one-bedroom Park Avenue apartments. One would hesitate to call it cluttered but it is packed to the brim with his “collection of presents, mostly drawings from artists I have been lucky enough to know”, Richardson says. Those holdings are a veritable treasure trove and tell of his remarkable friendships with pivotal artists. Among them are reams of gifts, letters and photographs from Picasso. “He would sometimes embellish the letters his wife Jacqueline wrote to me or Douglas with little vignettes,” says Richardson in the book. Many of the objects are gifts, too: a towering pair of art deco glass candlesticks was given to him by his close friend Annette de la Renta, the philanthropist who is trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—her recent birthday present to him was a bizarre puppet of Donald Trump. Another present was a leopard-spotted carpet from the late interior designer Mark Hampton.

But it is the art that speaks to his most famous friendships: there is Richardson’s portrait done by Lucian Freud, which he describes as “a trial run for the royal commission [Freud’s 2001 portrait of Queen Elizabeth II], for which Lucian was allotted only eight sittings”. Although Freud’s portrayal of the Queen remains controversial in some circles, Richardson begs to differ: “Lucian would ultimately become the greatest portraitist of his time,” he says. Elsewhere are drawings by Braque, César and, of course, Warhol. Richardson immersed himself in artistic milieux wherever he went—just as he met Freud and Bacon in London in the 1940s, in New York he frequented Warhol’s Factory and later partied with him at the infamous Studio 54 along with starlets of the era like Bianca Jagger and “Baby Jane” Holzer. Richardson delivered the eulogy at Warhol’s memorial service in St. Patrick’s church in 1987.

John Richardson's home with his portrait by Andy Warhol © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

Warhol’s riveting portrait of him sits above a cunning picture of his calico cat Lulu, while nearby is a Roman bust of Lucius Verus. It is typical of the diversity of objects: Richardson has effortlessly conjured up the ultimate kunstkammer. Alongside prize paintings are narwhal tusks, suzani and ikat textiles draped over sofas and chairs, large white tortoise shells hung against dark Venetian blinds. Many of his collecting instincts derive from his time at Christie’s—he set up the New York office with his friend Harry Allsop. There, Richardson plucked up 18th-century English furniture “for a song”, he says, “and now no one wants it”. He had an eagle eye for furniture just as he does for Picasso’s works: once, in Paris, he snapped up a red-canopied bed for the equivalent of £15. “I discovered it had the mark of Versailles,” he says while pointing to it, close to where we sit. As we speak, Richardson is seated in his turquoise study at his massive 18th-century campaign desk. In a trice, he demonstrates how easy it is to take apart, “so it can be transported to battle fields”, he says.

During his time at Christie’s, Richardson notes in the book, “every penny I earned went to finds that seldom served any purpose: a giant tortoise (stuffed), a jester’s rattle, a silver chamber pot, daguerreotypes of the royal family and circus freaks”. His holdings were not all snared at Christie’s or acquired through gifts of the great and good, though: some were found at junk shops. Along the way he has snapped up peculiar objects from an enormous coral brain to an apron devised from giraffe tails. Elsewhere is a profusion of blue and white porcelain. A whale penis measuring some eight feet in length pokes out of a potted palm.

Somehow it all fits in comfortably, even the art that leaps across the centuries, from Alex Hoda’s massive three-dimensional relief in black rubber with its fierce monsters to a Joshua Reynolds portrait of Frederick, Prince of Wales. Of his approach, Richardson says: “Period rooms tend to bore me. The more historically correct that they are, the more museum-y they look. I like to mix things up so that they galvanise each other to life.” He admits his holdings are a bit of a “hodge podge”, however. “I mix them all together—same as I do with my friends,” he writes in the book. “The jumble works, at least for me, but then I’m a bit of jumble myself.”

• A version of this article will be published in the forthcoming April issue of The Art Newspaper