The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report released today reveals an increasingly top-heavy—and male dominated—industry in which many smaller galleries are in the dangerous position of relying upon just one artist for half of their income.

The third edition of the report, compiled by the economist and founder of Arts Economics Clare McAndrew, has found that an average of 63% of sales made in 2018 by primary market galleries came from their top three artists and 42% from just one leading artist. This figure was higher for smaller primary market dealers with turnover less than $1m—for them, 45% of total sales value came from just one artist. For larger galleries with turnover exceeding $10m, value was more spread out and only 29% of sales came from their top artist.

“The most interesting thing for me was the very precarious position that that a lot of primary market galleries are in because their income is so reliant upon such a small number of artists, particularly the smaller galleries,” McAndrew says. “If those artists leave or the bigger galleries take them away, it leaves them in a very dangerous position.”

This precarious position, McAndrew says, is compounded by two other factors: “Coupled with this, galleries across the board say banks won’t finance them at all, so they are forced to take money from all sorts of sources to keep afloat. And then there is the high expense of exhibiting at fairs, and the delayed income from these as payment for sales is rarely fast. It’s a very risky business to go into. It’s attractive and exciting but you need to be very hardworking and brave.”

Although much talk has been devoted to the plight of small and mid-sized galleries, with repeated suggestions that larger galleries should pay a football-style transfer fee when taking on artists from smaller operations, McAndrew “nothing really seems to get done.”

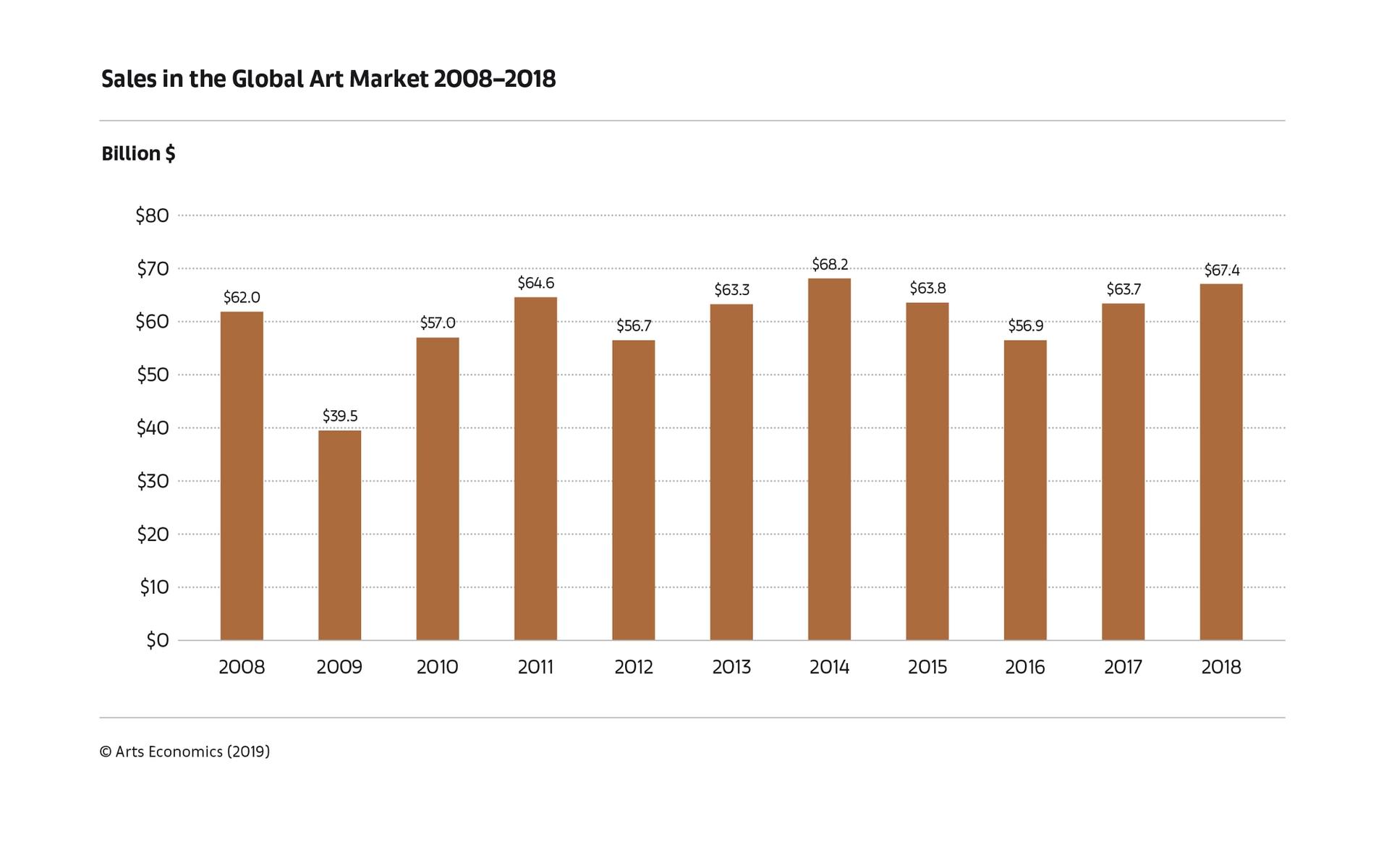

Global art sales over the past decade, as calculated in the latest Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report © Arts Economics (2018)

This is reflective of the increasingly top-heavy nature of the global art market, which McAndrew calculates grew overall to $67.4bn (up 6% year-on-year) in 2018, the second highest level in a decade. Last year, dealers with annual sales below $250,000 reported the biggest drop in turnover (18%) and, on average, all dealers with a turnover of below $500,000 suffered reduced sales. However, those galleries with annual sales above $500,000 all grew, particularly at the highest end—galleries with turnovers between $10m and $50m saw sales rise by 17%. Overall, sales in the dealer sector rose 7% year-on-year to an estimated $35.9bn.

The auction market mirrors this flight to the top end—works sold for over $1m (a mere 1% of lots) accounted for 61% of auction sales last year, which totalled $29.1bn (up 3%) according to McAndrew’s findings.

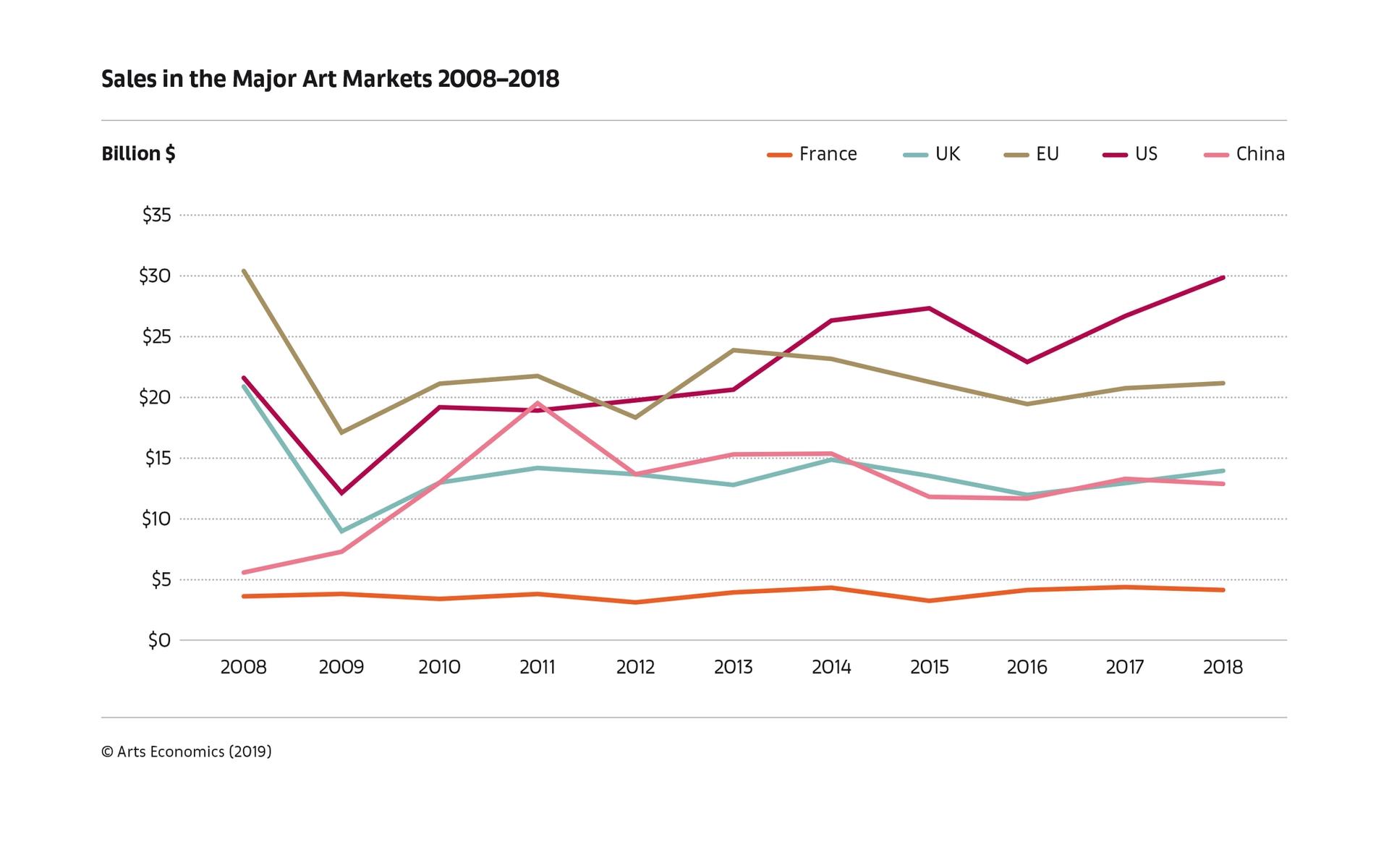

The market is also heavily concentrated in the US, UK and China, which together account for 84% of total sales by value. The US leads, with a market share of around 44% and sales reaching $29.9bn which McAndrew says is the highest level to date. Surprisingly, in the face of the looming Brexit deadline, the UK bore up well regaining second place with total sales of just under $14bn, up 8%. China’s previously insatiable growth, however, slowed as supply dwindled somewhat and sales dropped by 3% to $12.9bn.

More dynamic at the lower end, however, are online auctions, which reached a new high of $6bn in 2018 (up 11%), growing at double the rate of the rest of the market. This rise is in part thanks to the willingness of millennial high net worth collectors to buy online—according to a survey conducted by McAndrew and UBS of 600 high net worth individuals, 93% of the millennials said they have bought works of art or objects from an online platform.

Millennials are also the most active generation of buyers in the art market, the report says, and accounted for around half of collectors who regularly spend $1m or more. Additionally, the behaviour of these millennials has more in common with others of their generation than of collectors from the same region. “Regional buying traits are going to break down—it’s a reflection of the globalised times we live in and the importance of the internet which has changed how people are engaging with art,” McAndrew says.

The US remains the biggest art market globally, following by the UK © Arts Economics

Chiming with the zeitgeist, a particular focus of this year’s report is gender, both in terms of collectors (who are still largely men, though women are more influential in Asia) and the representation of female artists. “When I was looking for data on the representation of women in the gallery sector, it was all very ad hoc,” McAndrew says. “There was no real information about what was going on so I wanted to create a benchmark—a stick in the sand against which we could measure representation of women every year and see if it gets any better.”

Only 36% of the artists represented by galleries in 2018 were female, accounting for an average of 32% of sales, and (from a survey of 82 events) just 24% of the 27,000 artists shown at art fairs are by women. At auction, there is a “gender discount” of nearly 50% for works by women, and only two works by female artists have ever broken into the top 100 auction prices for paintings—despite women being the subject of around half of the top 25.

McAndrew cites the Duke University sociologist Taylor Whitten Brown's research in the report, specifically the so-called Matthew effect, "in which advantage begets advantage". The cumulative effect of multiple disadvantages for women, such as the above differences in gallery representation, cultural bias, "the cliché of the art world ‘bad boy’", the onus of parenthood upon women, the lack of women in key decision making positions, and "the lack of assertiveness among female artists", are all posited by Brown as possible reasons for the imbalance.

“There has been an improvement over the past 100 years, but barely over the past 10 years,” McAndrew says. “There are many female artists coming out of art school, but for some reason they don’t make it into galleries or to the next stage of the market.” As for the reason for this, she is baffled: “I don’t know. Is it down to demand, or to do with the structure of the art market? Or is it that men and women make different art, and in which case why do we value art that exhibits more ‘masculine’ attributes more highly? It’s a big question, but we need to ask it because if it’s not the infrastructure of the market perhaps we need to change the goalposts. At least we’re now asking the question, even if we don’t have the answer.”

As for 2019, McAndrew says most people she spoke to about the coming year were worried, particularly about the high end of the secondary market: “Sales last year were strong but at the end of 2018 most people, even at the high end, were relieved that they had done well, rather than riding the crest of a wave. The unstable economic and political climate is weighing on their minds.”