Tracey Emin and Jay Jopling at New York’s Gramercy International Art Fair in 1994 © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved; DACS/Artimage 2019

Tracey Emin reclined on top of a narrative quilt. Nayland Blake, dressed in a bunny suit, invited visitors to climb into bed with him and snap pictures. A Tony Oursler head stashed in a cupboard muttered at passersby. When the lifts broke down, visitors had to climb 12 floors.

The Armory Show, now among the world’s most prestigious art fairs, began life in 1994 as the Gramercy International Art Fair in the rundown rooms and corridors of the Gramercy Park Hotel in New York. Today, some galleries pay upwards of $100,000 to exhibit at the fair. Yet it was once conceived as a gritty alternative to the handful of establishment events, such as Art Basel and Art Chicago (now Expo Chicago), that populated the early 1990s art fair landscape.

We broke the hotel’s banqueting record, and we broke their elevatorsPaul Morris, Armory Show co-founder

The idea of the downtown New York gallerists Pat Hearn, Colin de Land, Matthew Marks and Paul Morris, the Gramercy was intended to give a platform to a younger generation of galleries at a time when the art world had suffered a blow from a recession. “Whatever we came up with had to be a new economic model, as well as a creative one,” Morris says. “We wanted to find the straightest line between a gallery and an art fair.” The Gramercy had forerunners in a scattering of other fairs held in hotels and repurposed spaces, including Art Amsterdam at the Hilton Hotel in 1992, and the Unfair that same year in Cologne, an indie rival to the conservative Art Cologne.

The 1994 Gramercy was a low-overhead, low-risk proposition. Galleries covered the cost of the room plus an administration fee around $50; tickets to the fair cost around $10. “We were very naive,” Morris says. “At one point, David Ross, who had been the director of the Whitney, said you guys have to charge an entrance fee or people won’t take you seriously—which we really hadn’t thought of before.”

For dealers coming from further afield, such as Jack Hanley—then based in the San Francisco Bay Area—the hotel room-booths doubled as accommodation. “Staying the night there was like a 24-hour party… it felt like an avant-garde happening of some kind,” Hanley says.

I vividly remember going to the Gramercy Hotel in 1994 and walking in and out of rooms to see a radical presentation of art by leading dealers. It was quite unique and felt very much in the spirit of the avant-gardeAgnes Gund, philanthropist, chairman of board, MoMA PS1, president emerita MoMA

The Gramercy International Art Fair, in its original form, lasted five years, during which time it expanded to set up shop at Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles and The Raleigh hotel in Miami. “It was fantastic; it was incredibly convivial, and there were people from Europe, from Los Angeles—and this was at a time when the art world was less global,” the dealer Nicole Klagsbrun recalls of the New York fair’s early days. It came with its challenges, however: dealers were prohibited from putting nails in the hotel walls, and sales were relatively slow.

A fairgoer browsing in one of the hotel’s rooms (1994) Photo: Colin de Land Collection 1968-2008: courtesy of the Archives of American Art/Smithsonian Institution

But gallerists are nostalgic for those early days and generally agree that today’s Armory Show, and the overall art landscape, is an entirely different animal. Even Morris—who as founding director helped shepherd the fair to the Armory at Lexington Avenue and 69th Street, where it renamed itself as a tribute to the landmark 1913 Armory Show, and to two sprawling piers on Manhattan’s West Side—says that this is not the art world he personally signed up for.

“I think the art fair landscape is very, very crowded,” he says. But he also believes The Armory Show has in some ways remained faithful to its core values. “I see dealers that have been there since the Gramercy,” he says, “and I see younger dealers showing younger artists all through the fair. And that was really the mission statement.” In that original spirit, the fair recently announced an annual initiative, the Gramercy International Prize, granting one gallery a free space at the fair each year.

It was great fun; I met a lot of people who became friends for life. It was a very collegial fair, and that was the whole point of it. What was interesting was all the penniless people who went on to have quite successful galleriesClarissa Dalrymple, curator

Among those from the fair’s early days that are showing this year are 303 Gallery, Jeffrey Deitch and Tomio Koyama. Others, like Jack Hanley and Gavin Brown, have defected to Frieze New York or to newer fairs striving to cultivate the more playful, less commercial environment of the Gramercy, like Independent and the Los Angeles newcomer Felix, which launched in February. At some point, the Armory “just wasn’t as interesting”, Hanley says.

Klagsbrun also feels the Armory has lost some of its creative flair. “It’s not as fun, not as imaginative, not as friendly,” she says. “I think the way they deal with that is through all these sections to accommodate it, whereas before it didn’t need that.” (Since 2014, The Armory Show’s Presents section, for example, has counterbalanced presentations from blue-chip and mid-tier galleries with booths for galleries less than ten years old.)

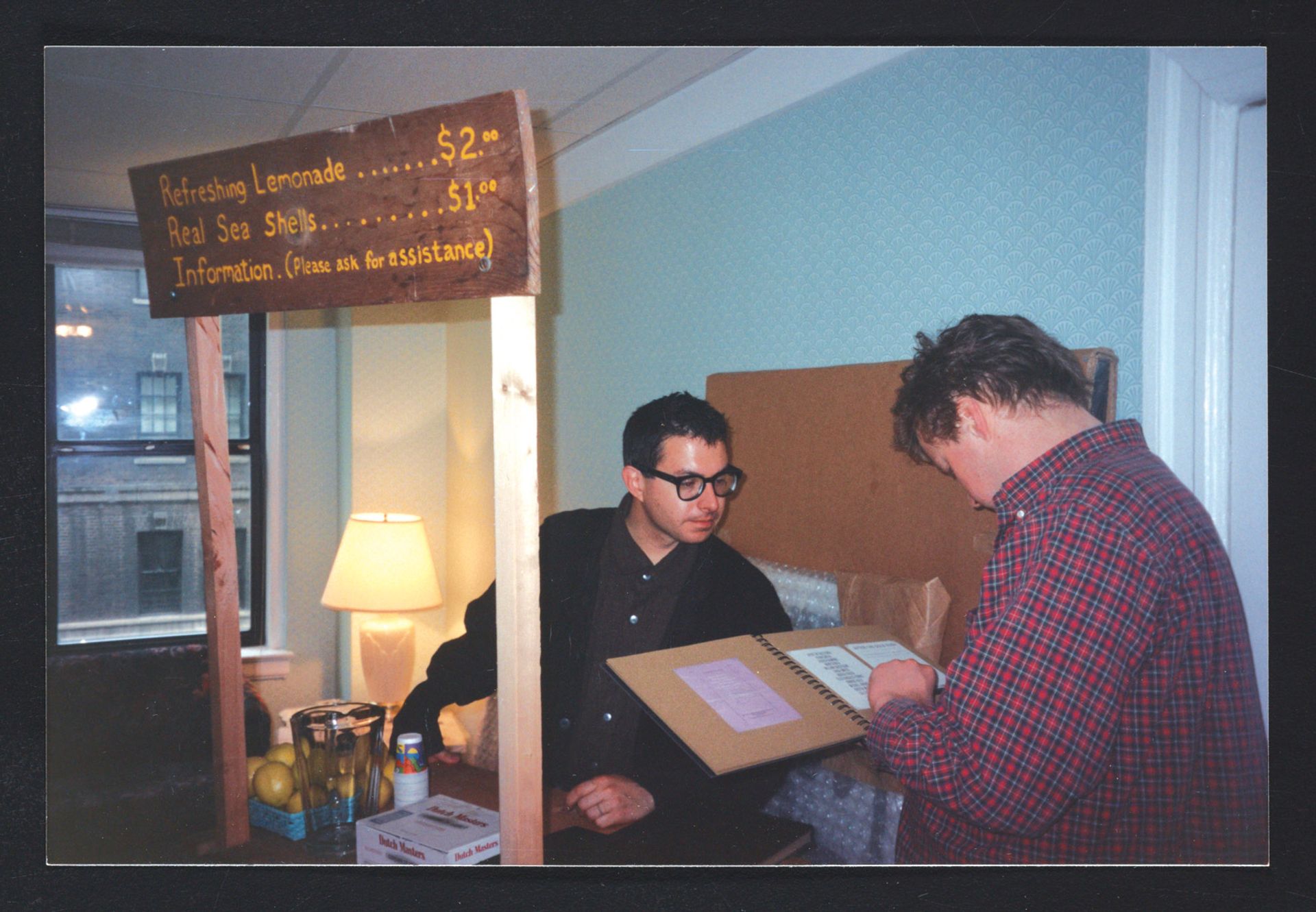

Mark Dion’s lemonade stand (1996) Photo: Colin de Land Collection 1968-2008: courtesy of the Archives of American Art/Smithsonian Institution

Would a fair such as the Gramercy be possible today? At the relatively scrappy Spring/Break fair, which offers free stands to independent curators, works by emerging artists go for thousands. Morris contends that a return to the old Gramercy would require high-quality works priced in the mere hundreds. “It costs a fortune to have a gallery these days, and that’s reflected in the prices of younger artists,” he says. To return to the Gramercy days, “you’d have to have something where I could bring an uninitiated couple there and they would spend $500 on a great drawing by a young artist”.

However one views the fair’s transformation, it is undeniably a juggernaut, and several once-penniless gallerists have gone on to cultivate highly lucrative businesses. “We were told all along that it would never work because New York was already an art fair,” Morris says. “Today, count the art fairs that take place in New York City.” It also helped to boost an art scene in peril. “The market was very weak at that point,” says Vincent Fremont, a founding director of the Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, who sold editions at the Gramercy. “From 1992 to 1994 it had flatlined. The Gramercy brought morale up. It gave people a sense that things could change.”