Not all collectors are great collectors, and some have an inflated opinion of their own good taste. That appeared to be the lesson of Christie’s 82-lot, three-in-one sale last night in London, catchily titled Hidden Treasures, Impressionist & Modern Art and The Art of the Surreal, which made a combined £140.8m (£165.4m with fees)—the second highest total for a Christie’s Impressionist and Modern sale in London, beating the equivalent £149.5m (with fees) sale last year.

But big numbers can blind us to nuance, and while Christie’s sale was high volume, it was Sotheby’s slimmer £74.4m (plus fees) sale the night before that was more consistent and well-pitched in terms of estimates, with 91% sold by lot.

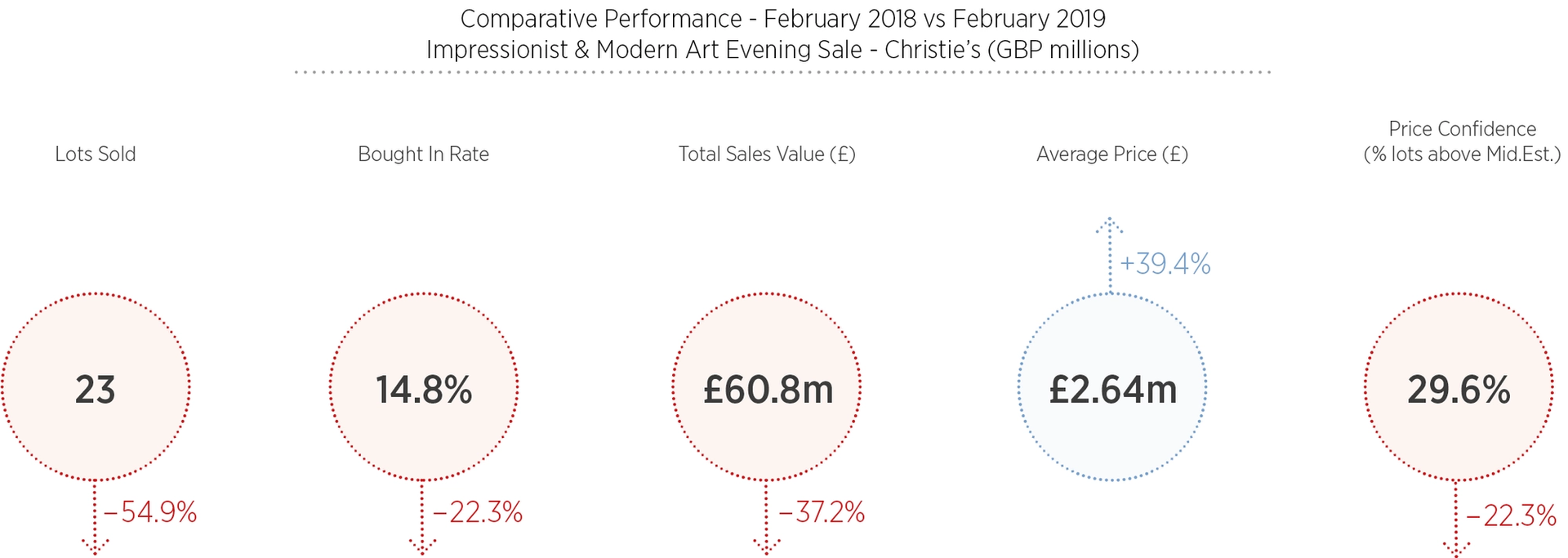

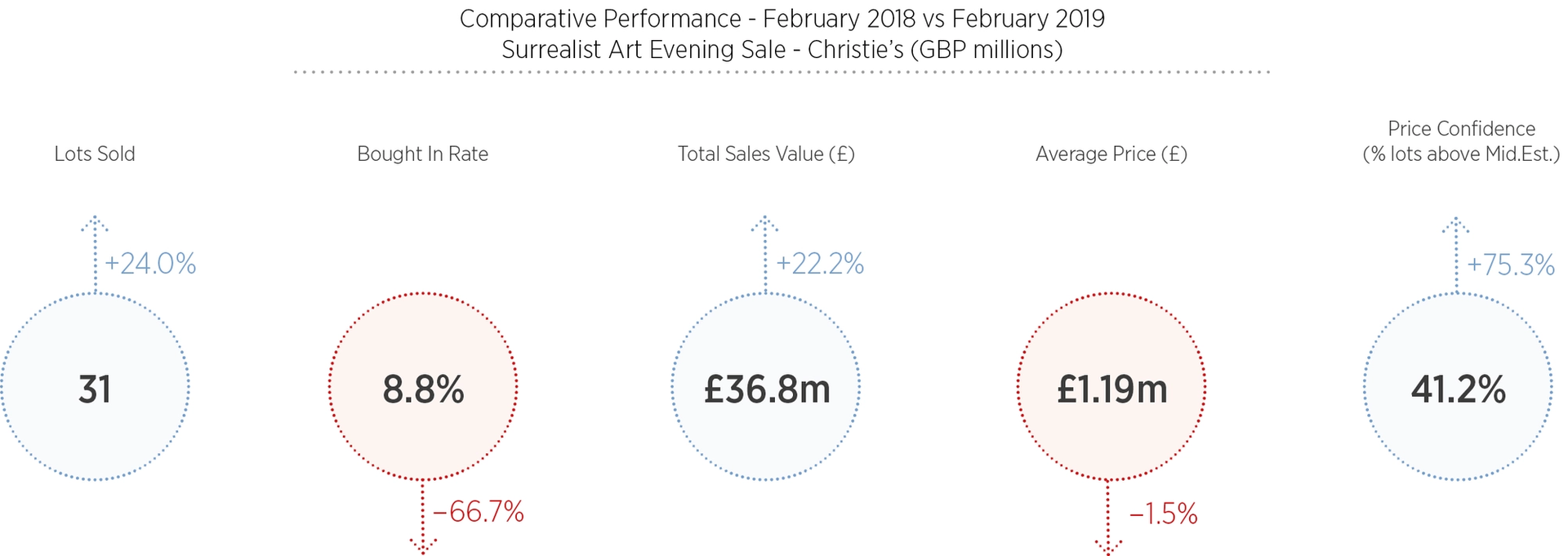

The analysis firm ArtTactic's comparison of Christie's February Impressionist and Modern art evening sale in 2018 and 2019 Courtesy of ArtTactic

At Christie’s, 82% of the 82-lot auction sold by lot, but it got off to a wincing start with the patchy take-up of a tick-box collection of Impressionist and Modern art that, reportedly, was being sold by Monte and Neil Wallace, octogenarian brothers from Boston who bought in the 1980s through Acquavella, Lefevre and Wildenstein galleries. The stiffly estimated collection failed to tick bidders’ boxes, so nine of the 21 “Hidden Treasures” will remain hidden for a while longer as they failed to sell against pushy estimates (a Bonnard and a Matisse were also withdrawn just before the sale).

A lot of big price tags to absorb, particularly in tricky economic times and the Hidden Treasures result was, said Keith Gill, the head of the evening sale: “A bit disappointing” thanks to “selective bidding”. Why did the Wallace brothers choose to sell a collection that epitomises classic East Coast American taste in the UK just before Brexit? “As we stand in London we are very focused on Brexit, but it’s not such a significant event globally,” Gill said, adding that the vendor understood “London is the most international of markets.”

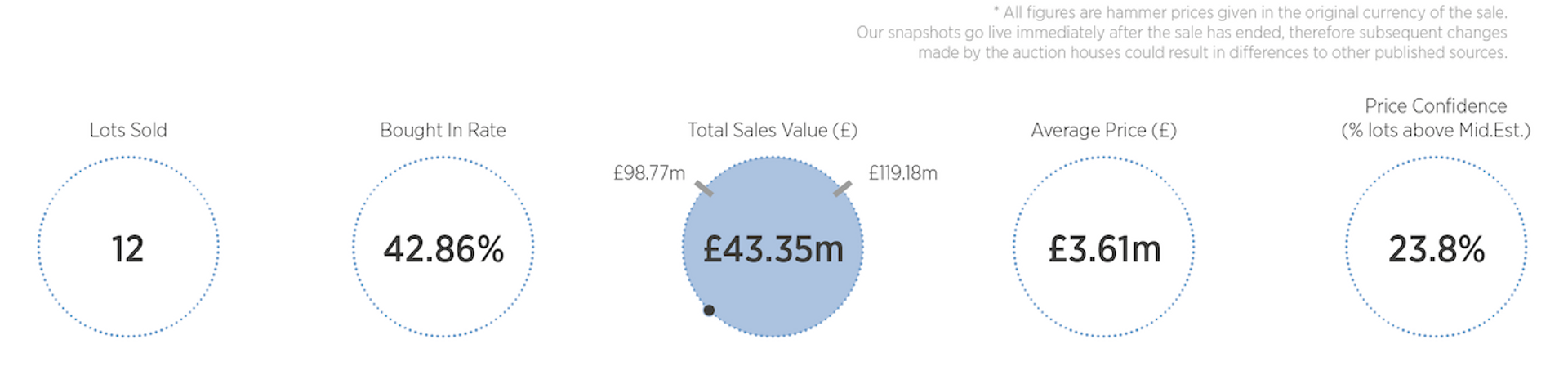

A breakdown of the Hidden Treasures collection results at Christie's, from ArtTactic Courtesy of ArtTactic

Top flop was the cover lot: Monet’s large-scale Saule pleureur et bassin aux nymphéas (1916-19), estimated in excess of £40m, drew only a painful silence from the room. Monet’s attractive painting of Irises also failed against a £4m-£6m estimate, and Van Gogh’s Antwerp period portrait of a woman got nowhere near its ambitious £8m-£12m estimate. However, the collection’s star (and the top lot of the whole sale) was Paul Cézanne’s Nature morte de pêches et poires (1885-87) which sneaked away just under its £20m+ estimate at £18.5m (£21.2m with fees) to the New York advisor Nancy Whyte.

“The material was fresh but the market is so selective now that anytime a vendor gets over-inflated ideas, the market rejects it,” says Emma Ward of the London advisors Dickinson. “It was sad as it set the tone for what would have been a good sale. If the estimates had been more moderate, I think a lot of it would have got away.”

According to Gill, the record $84.7m (with fees) achieved by Christie’s for Monet’s Nymphéas en fleur from the Rockefeller collection last May tempted the Hidden Treasures vendors to sell. But as Ward says: “You cannot base results on big name sales like the Rockefeller and Yves Saint Laurent, and the Monet in the Rockefeller apparently had three consecutive third party guarantees on it which pushed up the price.”

Edgar Degas's Danseuses dans une salle d'exercice (Trois Danseuses) Courtesy of Christie's Images 2019

The start of the mixed owner sale received a much-needed shot in the arm courtesy of a gem-like little oil by Edgar Degas, Danseuses dans une salle d'exercice (Trois Danseuses) from the desirable date of 1873. In contrast to some bloated estimates in the first section, this lovely exercise in tonal painting was estimated at a lean £800,000-£1.2m. The painting had not been at auction since 1912 and had passed down through the French aristocratic de Ganay family since 1936 (side-note: Adrien Meyer, the co-chairman of Christie’s Impressionist and Modern art department, is the son of Anne Marie de Ganay). Rightly, the painting had multiple bidders clamouring for it, including the London dealer Danny Katz bidding in the room. However, it went to Keith Gill’s phone bidder for £3.5m (£4.1m with fees).

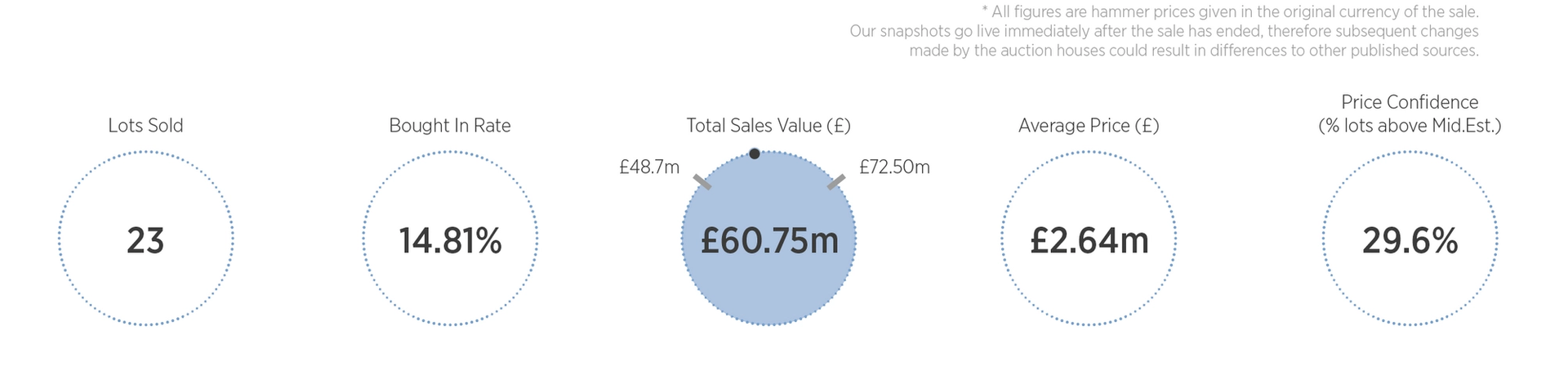

Lots in Christie's Impressionist and Modern art mixed owner sale last night averaged a hammer price of £2.64m according to ArtTactic's analysis Courtesy of ArtTactic

Six paintings by Paul Signac, Gustave Caillebotte, Félix Vallotton, Édouard Vuillard and Giovanni Boldini, reportedly from the collection of David Graham, a Canadian cable TV entrepreneur who bought in the early 2000s and died in 2017, fared far better than Hidden Treasures. Chief among them was Signac’s glowing Le Port au soleil couchant, Opus 236 (Saint-Tropez)which sold for £17m (£19.5m with fees) in the middle of the £12m-£18m estimate—a new artist record.

The buyer of the Signac was a mysterious young man and woman, bidding with two different paddles but sitting together. Soliciting much whispering from London dealers who had not seen them before, the pair were splurging on light-infused landscapes, hoovering up three of the best here: the Signac; Gustave Caillebotte’s spring-like scene of a man and woman walking in a garden, Chemin montant (1881) for £14.5m (£16.6m with fees, also an artist record) and, from the Hidden Treasures sale, Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s dappled view of a tree-lined country path, Sentier dans le bois, for£11m (£12.6m with fees)

René Magritte's Le pain quotidien, which was stolen in 1968 and restituted last year, sold for £3.3m with fees Courtesy of Christie's Images 2019

Art of the Surreal

No mere afterthought, the final 34-lot Surrealist section of the sale was testament to Olivier Camu’s long-time pursuit of this market. “This has been my hobby on the side,” he said. The Christie’s international director and co-head of the Impressionist and Modern art department started the dedicated annual sales in 2001 and this, the 18th edition, was 94% sold by lot (only two works failed to sell, and only one was guaranteed). The main man, as at Sotheby’s the night before, was René Magritte, an artist described by Camu as “Areligious, apolitical and acultural,” hence his broad, and growing, appeal.

ArtTactic's comparison of Christie's Surrealist art evening sales in 2018 and 2019 shows a 22% rise in total sales value Courtesy of ArtTactic

Seven works by the Belgian were offered, the most expensive being Le lieu commun (1964), a late and large painting of Magritte’s signature motif, a bowler-hatted man. The work, consigned by an Asian collector, had never been at auction before and, Camu said, “is one of the four or five large 3-D, hyper-realistically painted bowler-hatted men paintings still in private hands.” It sold to Camu’s phone bidder for £16m (£18.3m with fees) against an estimate of £15m-£20m.

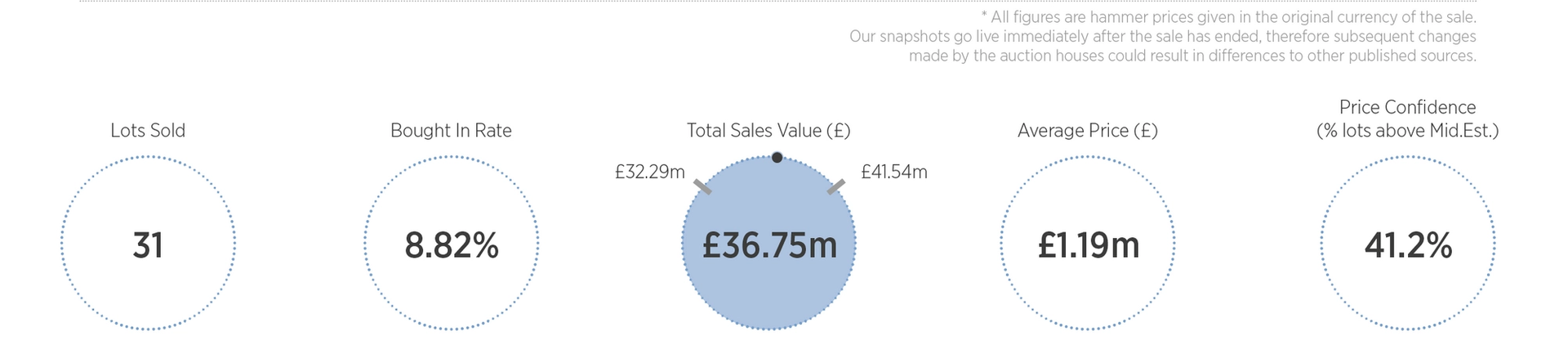

ArtTactic's analysis of the Surrealist sale reveals an average price of £1.1m Courtesy of ArtTactic

Another Magritte that drew strong interest was Le Pain Quotidien (1942), of a woman floating amid clouds, which had been stolen from the Brussels-based collector Jan Van Haelen in 1968 and was found only recently in the Dallas Museum of Art in Texas, when it was restituted to the Van Haelen heirs (meaning Christie’s were dealing with a casual 32 consignors). The old stretcher was still in Van Haelen’s house from when it was stolen, and the painting has been reunited with it. Estimated at £2m-£3m, at Christie’s Le Pain Quotidien sold to the New York advisor Nancy Whyte, also the buyer of the Cezanne still-life, for £2.8m (£3.3m with fees).