The non-Islamic art world has surely reached peak nudity. Clothes-shy bodies of all genders, ages and orientations have been prevalent for some time in photography, film, performance, painting and sculpture. Instead of the proverbial fig leaf we may (if we’re lucky) see a sign warning of imminent adult content. Now even “serious” art publishing is getting down and dirty. It’s #MeNudeToo.

The most impressive of the recent deluge of books on the subject is The Renaissance Nude, edited by Thomas Kren. Readable, informative and sometimes startling, it is the catalogue to an exhibition at the Getty last year which will come—in mutilated form—to London’s Royal Academy this spring (3 March-2 June). Time was when Getty’s paintings’ curators struggled to gain approval for purchases of nudes: apparently no longer. Rather than being fixated on Humanist Italy, the eight essays and 112 catalogue entries underscore the key role played by Christian iconography (Adam and Eve, Bathsheba, Christ’s Passion, St Sebastian) and by northern European patrons, especially French rulers, who, it seems, have always been partial to a bit of flesh. We learn about bath-houses (the easiest and cheapest place to see naked bodies), neo-Platonic alibis for nudity, and the depiction of witches. Here the definition of the nude is expanded to include topless imagery: examples range from male flagellants to Jean Fouquet’s bare-left-breasted Melun Madonna (not coming to London), possibly modelled on the French king’s mistress. T.S. Eliot’s lines come to mind: “Uncorseted, her friendly bust/Gives promise of pneumatic bliss.”

There are omissions and imperfections, however. There is no mention of Zodiac Man, or illustrations to Dante’s Inferno and Purgatory—the most plentiful modern source of nudity in the 14th and 15th centuries. Decorative arts objects such as historiated maiolica are also missing. Andreas Vesalius’s 1543 treatise on anatomy is mentioned just once in passing, yet its evocative illustrations of “live” dissected bodies standing in landscapes like martyrs are at least as important as Michelangelo’s contemporaneous Last Judgment. No one has a good word to say about Kenneth Clark’s classic The Nude, though he haunts the whole enterprise. His distinction between the (Gothic/Northern) naked and the (Classical/Mediterranean) nude is reheated with mounting hysteria by Stephen Campbell in his melodramatic Unruly Bodies: the Uncanny, the Abject, the Excessive.

Sometimes the largely libertine thrust goes too far. In an otherwise interesting essay on “personalised nudes”, Ulrich Pfisterer claims a nude self-portrait drawing by Dürer expresses the phallic root of his creativity (penis as pen/brush/burin). Yet it is an unfinished study rather than a credo. The awkward angled pose, odd spotlighting of one shoulder, and baggy bloated genitals, may explain why it was put aside. Most scholars think he looks ill. In Dürer’s illustrated treatise on human proportion, creativity is located in the imagination (the brain), the biggest genitals belong to “fat oafish man” and “rustic man”. In his most heroically physiqued nude self-portrait, Dürer wears a loincloth. Size does not always matter; less is often more. The same was true of female breasts: small (and pertly pneumatic) was beautiful.

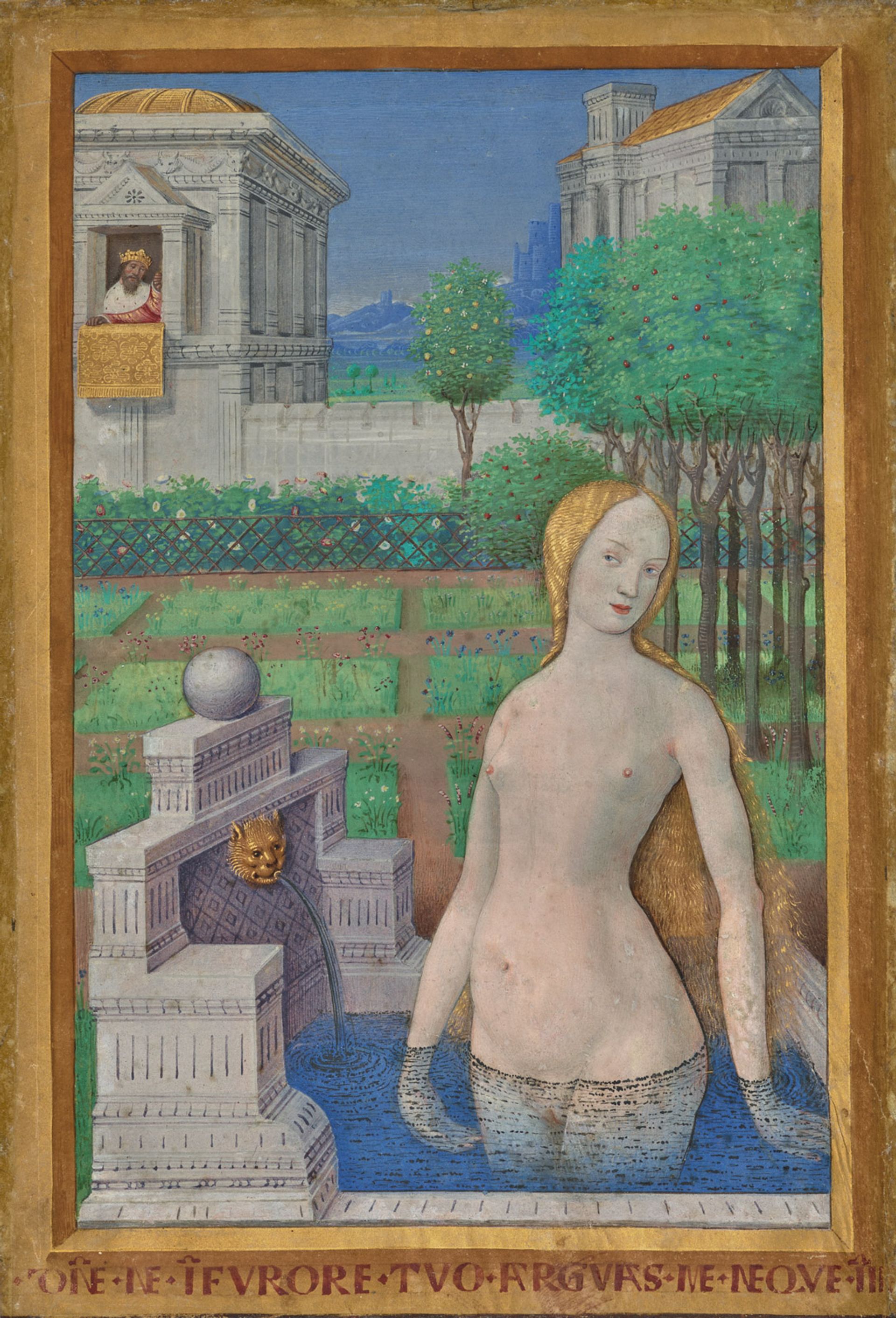

Jean Bourdichon’s Bathsheba Bathing, a miniature from the Hours of Louis XII (around 1498) ©The J Paul Getty Museum

Jill Burke contributes a useful overview of the rise of life drawing to the Getty catalogue and her book, The Italian Renaissance Nude, is full of fascinating tidbits. She is best on the social history of nudity: shaming rituals where prostitutes and criminals were paraded naked, the acceptability of childhood nudity, the association of nudity with poverty, ideas of virtuous nudity, courtesan culture. I do not think, however, we should read so much into the fact that copulating couples usually wore undershirts: this was the Little Ice Age, with no central heating or double glazing, so people slept in box beds or with curtained testers.

The relationship of social norms to actual works of art is not always so well handled, however. When provocatively arguing that Donatello’s David would not have been considered erotic because he was a child, Burke never considers that Cupid was also a child (the feather that caresses David’s leg may allude to Cupid’s wings). She also assumes that the systematic description of female body parts is a 16th-century innovation, evidence of the “period eye”. “Head to toe” description is in fact a classical trope that remained popular during the Middle Ages.

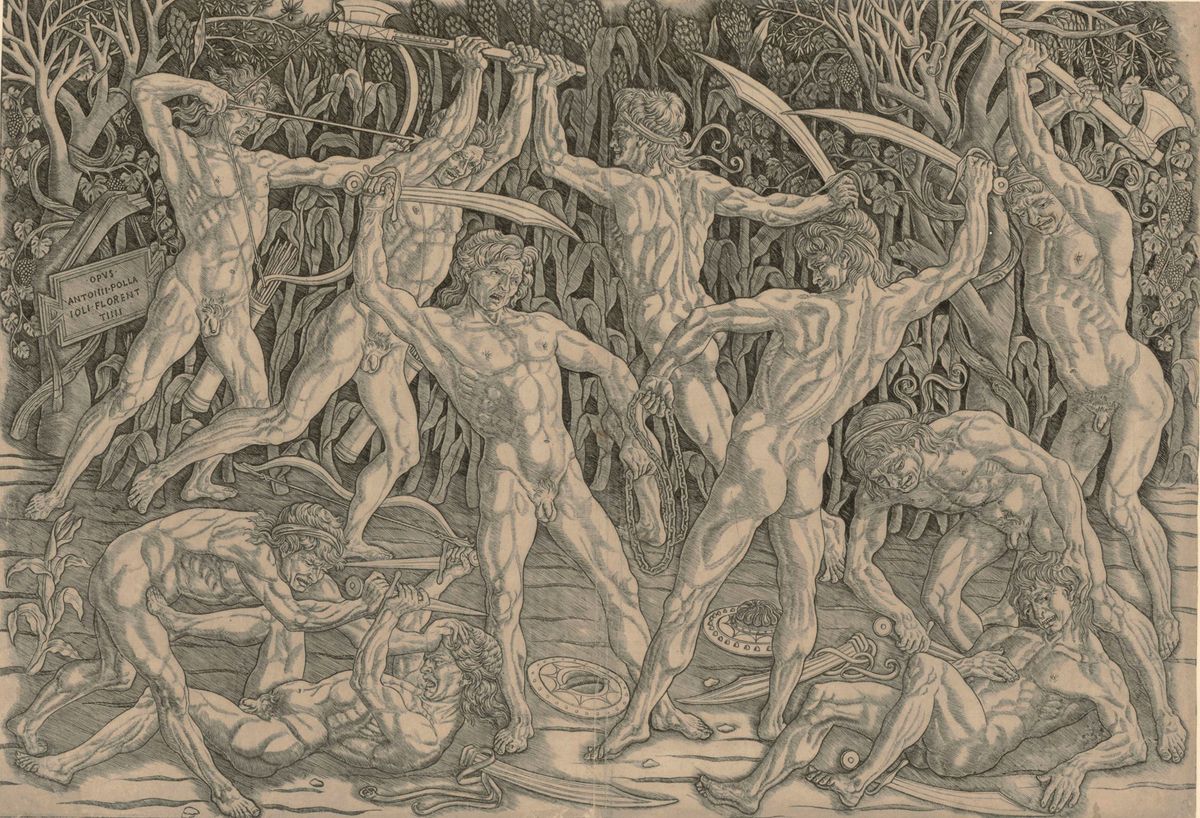

What most mars Burke’s book is her cliquey devotion to current academic pieties and protocols. She keeps name-checking other scholars in the text—“so-and-so says…”. It smacks of networking and gives the book an alienating patchwork feel–like Zeuxis selecting the best body parts from numerous women. Of Antonio Pollaiuolo’s famous Battle of the Naked Men engraving (around 1465-75), she announces grandly: “As I have discussed in detail elsewhere, the approach to nakedness here reflects that of contemporary travel accounts that discuss the savagery of naked sub-Saharan Africans.” She cites Alvise Cadamosto’s description of “bestial” black warriors in Senegal fighting naked with round shields, spears and curved swords. While there are black soldiers in the background of Pollaiuolo’s Martyrdom of St Sebastian, the naked men here are definitely not black–they are ancient Romans or Tuscans. Pollaiuolo’s scenario is an all’antica equivalent of the chivalric pas d’armes, where a shield or shields would be hung on a tree by a road as a sign to passing knights that they would be challenged. Fighting was often on foot, with axes, swords, daggers and bucklers. The curved swords in Pollaiuolo’s print are European falchions. Burke never explains that Cadamosto was a Venetian slave trader whose travel writings were only published in 1507.

Patricia Lee Rubin’s Seen from Behind: Perspectives on the Male Body and Renaissance Art is a celebration/manifestation of the fetishistic disorder known as pygophilia. Art historians have long regarded figures shown from behind (Rückfiguren, to use a frequently used German coinage not mentioned here) as a distinctive feature of Italian Renaissance art, one that creates variety, drama and depth. Rubin, though, sees it as a homoerotic move, to highlight the male bottom (although seated nudes, where the bum is barely visible, are included). She is working in the slipstream of detail-fetishists like Giovanni Morelli (you can attribute pictures by looking at “minor” details like ears and fingernails) and the sex-fixated Sigmund Freud.

Agnolo Bronzino's San Sebastian (c.1533) © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Rubin’s best bit shows how the naked male bottom in art went from being an object of disgust, associated with peasants and buffoons, to one of beauty and desire. But although we are repeatedly invited to admire “taut butt cheeks” (I prefer to call them TBCs), often sheathed in Lycra-tight clothing, her book is flabby, wobbly and in need of major liposuction. Much of it is a generalised standard essay on male nudity, homoeroticism in art and life, and sculpture in the round, with random forays into modern art. Her beloved behinds often get left far behind. She has no discernible method, and does not pre-empt counter-arguments.

If TBCs are an inevitable incitement to buggery, then would not parted lips be an invitation to fellatio, and the looming rear-ends of horses—an even more striking feature of Italian art, exploited by Veneziano, Pisanello, Uccello, Gozzoli, Tura, Piero, Pinturicchio, Raphael etc–to hippophilia? Rubin should have mentioned that the male nude Rückfiguren in Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina would have echoed the rear-view horses in Leonardo’s matching fresco, Battle of Anghiari. Does not a rear view sometimes censor the more risqué frontal view of the genitals? (One might note that the latter, rather than the former, were covered up on Michelangelo’s David and Last Judgment). Are not TBCs occasionally just an elegantly designed junction between torso and legs?

Rubin’s writing is super fruity: “the cocked hip and perky butt cheeks”, “Peachy buttocks”, etc. The Literary Review should consider this loony mooney prose for its Bad Sex in Fiction Award.

Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body is the catalogue of a major Met Breuer exhibition highlighting polychrome sculpture from the Middle Ages to the present day. There are notable works such as the Auto-Icon of Jeremy Bentham (1832), incorporating the philosopher’s bones and hair, a Sèvres bowl (1787-88) modelled on a female breast, Lucio Fontana’s glazed ceramic Crucifixions (around 1950) and a mini exhibition of Spanish polychrome wood sculpture. As a picture book it scores highly; as art history, it is–to put it mildly–a disgrace. It is not so much the surfeit of 15 essays of varying degrees of relevance and insight written by a disparate bunch of curators, artists and cultural theorists, or that we tire of being told that polychrome sculpture is invariably a “disruptive” force due to its lurid realism; it is that polychromy is put in binary opposition to white marble sculpture, whose post-medieval primacy is seen as an expression of white supremacy.

Unsurprisingly, scant evidence is given for this facile Europhobic generalisation, which has already become influential. White artefacts have been prized in many cultures because of their association with purity, light, spirit, truth–whether it be porcelain, cloth, paper, vellum, alabaster, shell, bone, ivory or whitewash. Kate Ezra, in her Met book African Ivories (1984), observed that in Benin ivory “reflects the symbolism of white chalk, whose ritual purity is associated with [the god] Olokun”. Cécile Froment of Yale University recently underlined the spiritual importance of white in the Congo.

Black-brown bronze was, in fact, the prime medium of excellence and, from the Renaissance onwards, of global statuemania. Bronze alone was used for the most prestigious and expensive sculptures, such as equestrian monuments. The curators would have been better off attacking the cultural imperialism inherent in Victorian white ceramic toilets. The medium is not always the message.