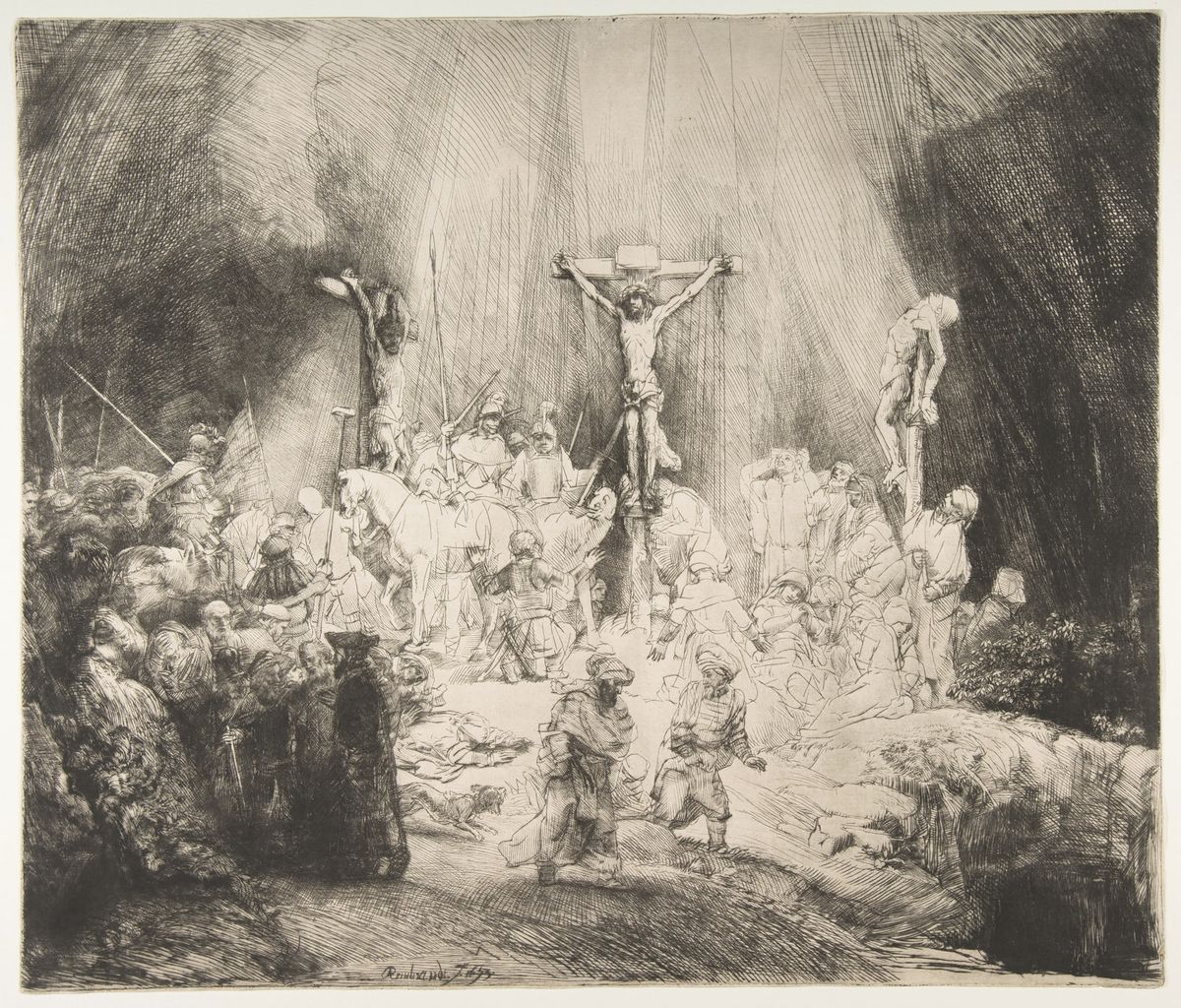

Three and a half centuries after Rembrandt’s death, questions persist about his creative process, including the pace at which he often reworked the surface of a copper printing plate to create multiple states of an etching. As scholars seek to document the various states, watermarks have proved an invaluable tool, allowing them to trace different impressions to specific batches of paper that the artist bought for his workshop and to thereby date the print.

Now students and professors at Cornell University are developing a website that will allow a user to upload an image of the watermark found on a Rembrandt print and then quickly classify it. Supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, they hope to have the online interface ready by the end of the summer, says Andrew Weislogel, a curator of earlier European art and American art at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell, who has helped lead the effort. The website will be tested by partner academic institutions before it becomes available to all.

Known as the Watermark Identification in Rembrandt’s Etchings (WIRE) project, the Cornell initiative is built on scholarship that was launched in the 1990s by the paper conservators Nancy Ash and Shelley Fletcher and expanded in a 2006 book by Erik Hinterding, now the curator of prints at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Relying on advanced imaging techniques, Hinterding grouped watermarks on Rembrandt’s prints into 54 basic types, then further divided them into 294 variants and 512 subvariants.

The European paper mills of Rembrandt’s day vied to come up with distinctive watermarks but also borrowed heavily from one another, leading to marks that varied in only minuscule ways. In addition, some paper makers began to attach a second watermark known as a countermark to the wired moulds they used in the manufacturing process, increasing the number of subvariants.

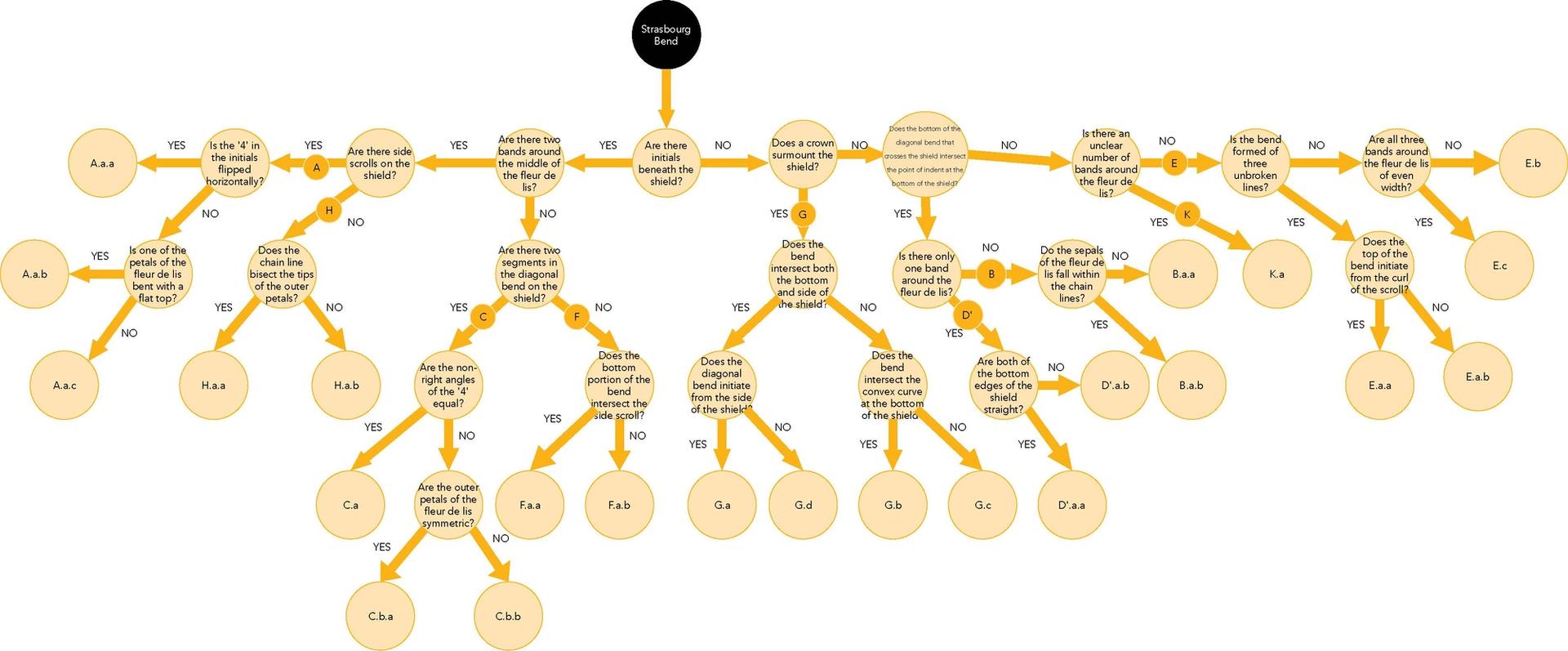

Combing through Hinterding’s subvariants to find a match for a watermark can be exhausting. So the WIRE project, which unites art history and engineering students, set out to create a digital “decision tree” for each of the 54 basic types. Each branch guides a researcher through a simple series of questions supported by corresponding images, such as: “Are there initials beneath the shield?” and “Does a crown surmount the shield?”. The user eventually arrives at a confident match, which can help him or her approximately date the work and then view other impressions of the Rembrandt print found on the same paper.

A "decision tree" for the Strasbourg Bend type of watermark WIRE (Watermark Identification in Rembrandt's Etchings)

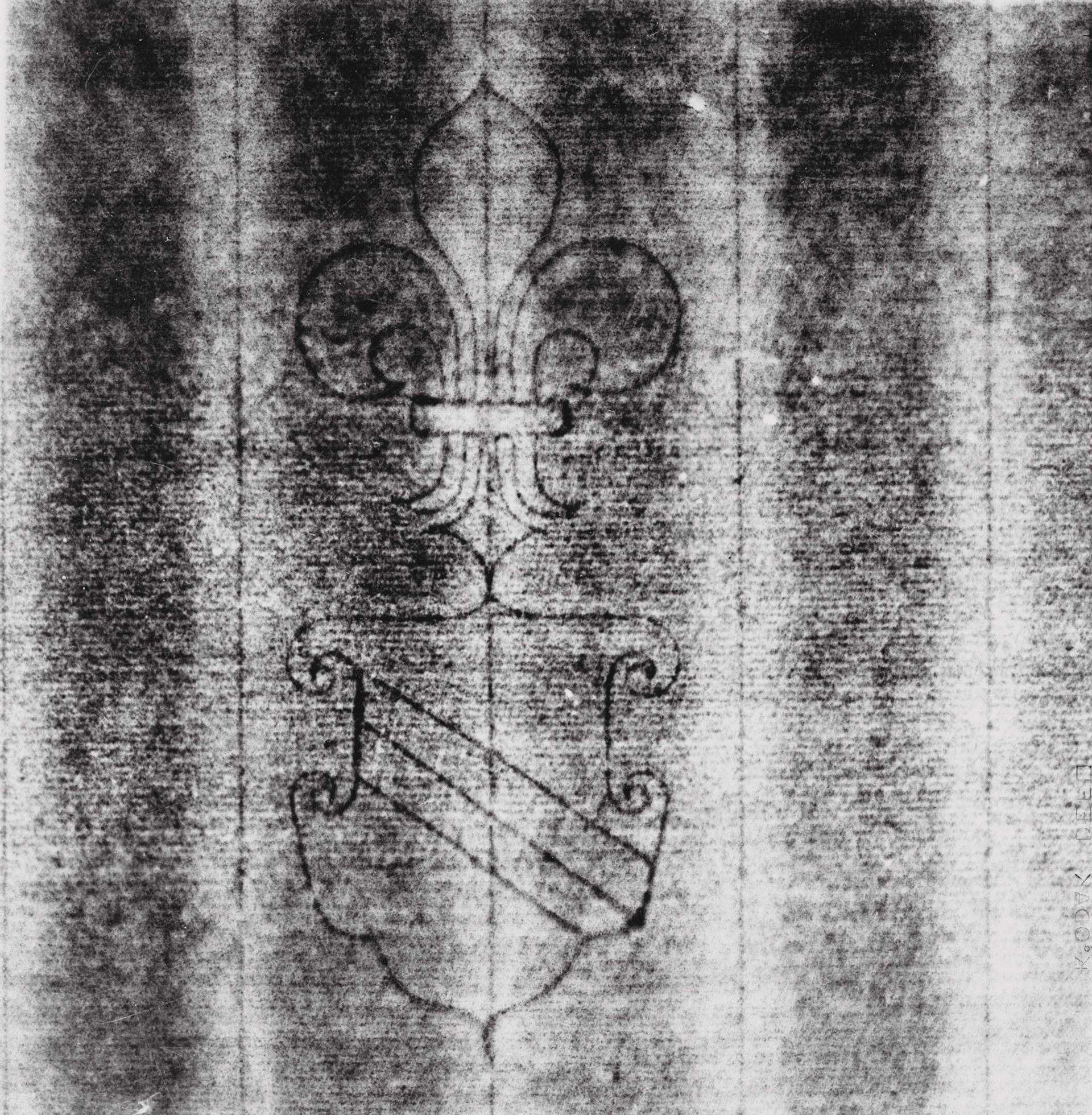

Watermark found on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Christ Crucified between the Two Thieves: The Three Crosses, Rembrandt (1653) Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

To develop their questions, the students have looked at photographs, beta radiographs and low-energy X-rays of watermarks of Rembrandt etchings from the collections of many university museums as well as institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Weislogel says. Ultimately, he hopes that WIRE will be able to build a database of prints and watermarks from US collections with rich Rembrandt holdings. (Hinterding’s research focused on prints at institutions in Europe and on the East Coast of the US only.)

Charles Richard Johnson Jr., an engineering professor at Cornell who has also overseen the initiative, says that one of the dividends is the cross- pollination of skills between the humanities and engineering students. “The art history students, with their grounding in connoisseurship, have to teach the engineers how to do close looking and see the distinctions” between the watermarks’ characteristics, he says, while “the engineers have the computational skills” and “can guide the art history students in thinking in terms of algorithms”.

Among other insights drawn from the watermarks, the students have gained an appreciation of how quickly Rembrandt worked, with multiple states of a print sometimes appearing on the same batch of paper. “He’s working really intensively on the plate, making these changes very rapidly, not letting it sit around,” Weislogel says. The students have also witnessed how the artist would sometimes return to a plate after he was seemingly finished with it, reworking the imagery carved into the soft copper or trimming a rectangular plate down into an oval portrait, for example, to create a saleable new edition for his print-buying public. Watermarks can also signal that additional prints were made after Rembrandt died and a plate had passed into someone else’s hands.

One limitation of the project is that watermarks only appear on European papers; Rembrandt also occasionally printed on Japanese papers. And only about a third of Rembrandt’s etchings printed on European papers have a watermark or a fragment of one. (An impression from a small plate might be printed on a portion of the piece of paper that did not include a watermark, for example.)

Still, as highlighted in a recent exhibition at Cornell’s museum and the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College in Ohio, the WIRE project has made strides, even discovering about a dozen watermarks that did not appear in Hinterding’s book while learning more about the artist’s methods.

“This really emphasises the materiality of Rembrandt’s prints,” Weislogel says, “rather than limiting our understanding to the surface image.”