“This is the Golden Age of contemporary African art. This is our renaissance. Within ten years we will look back in shock and awe at what we’re trying to achieve now because I think it’s going to change radically.”

So says Dolly Kola-Balogun of the young Nigerian gallery Retro Africa at the second edition of the 1-54 Contemporary Art Fair in Marrakech (until 24 February). Kola-Balogun, who co-founded the gallery in 2015, is a first-time exhibitor. “I appreciate fairs like this because they allow us to focus on the work coming out of Africa, on an international level,” she says, as the director of the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art in the US quietly hands her his business card.

There are a huge number of French speaking visitors at 1-54 Marrakech—many white but a number from across North Africa—and it does feel a little like African art for a European audience, enjoying some winter sun in the idyllic surroundings of the idyllic La Mamounia hotel.

It raises a question: who is this fair for and can it help to sustainably grow a domestic collector base on the continent at a time when African contemporary art is the hot young thing of the global art market?

Sanlé Sory, Les Jeunes Mélomanes (1974) Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery

Touria El-Glaoui, 1-54’s director who is herself from Morocco, says that while “it’s true” that white visitors dominate, “the number of collectors from sub-Saharan Africa has dramatically increased this year, and a lot of friends have come from Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal.”

However, El-Glaoui adds, “we [the fair and the galleries] need to build a stronger collector base across Africa.” Many established African collectors are great patrons but buy directly from artists rather than at fairs. El-Glaoui points to one visitor, Oumar Sow, the Senegalese collector who is in town: “He’s very good friends with all his artists, and a lot of the older generation of artists did not have galleries, so they have better contacts with the collectors than the galleries themselves.”

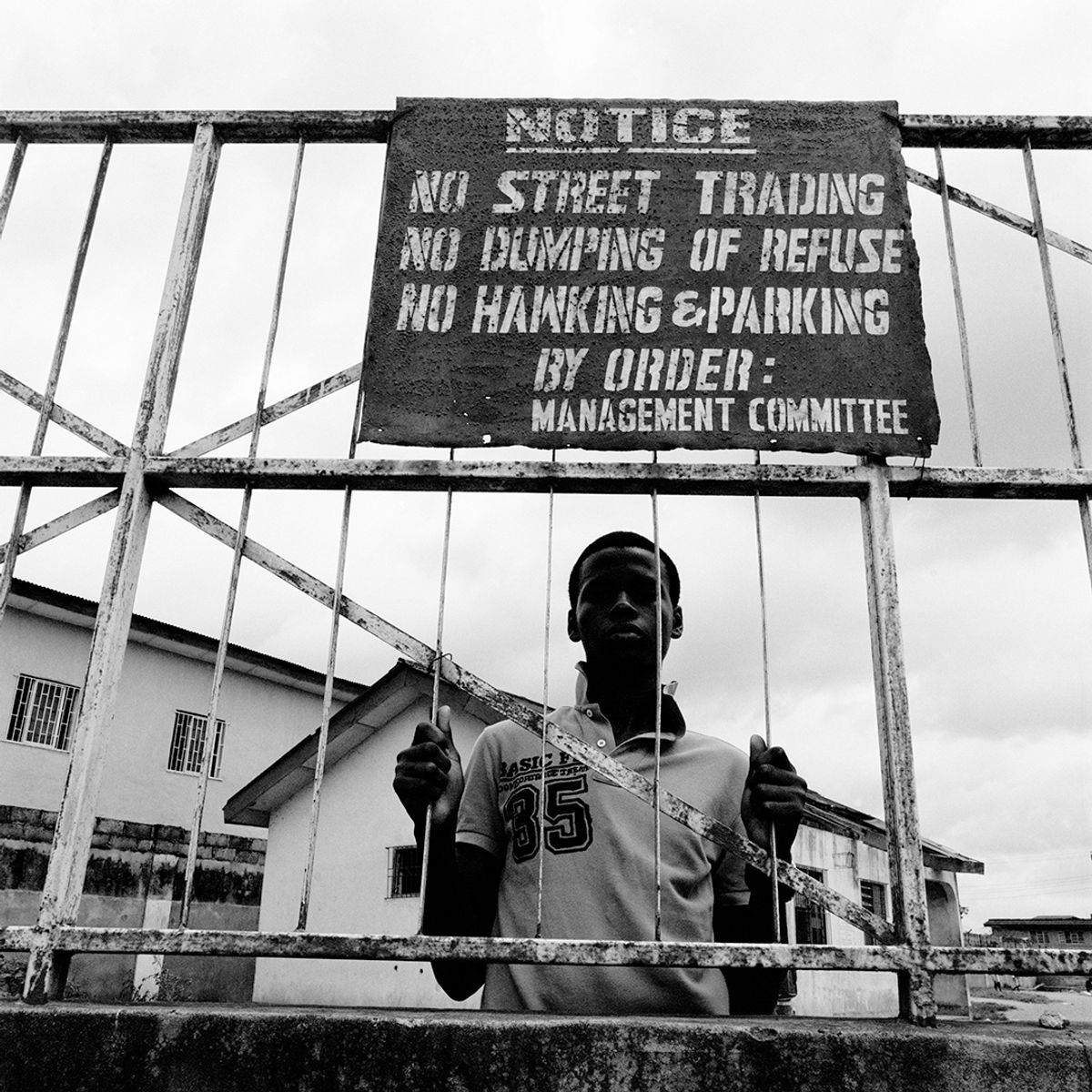

At 1-54 Marrkech, Retro Africa is showing three candid images taken on the streets of Lagos by the Nigerian photographer Uche Okpa-Iroha’s Isolation Series, priced at £5,000 each. That seems cheap for an established photographer and two-time winner of the Seydou Keïta Prize, awarded at the Bamako Biennale in Mali. “It is,” Kola-Balogunsays. “And that’s the problem for contemporary African art at the moment in terms of the market. If you look at Chinese or US artists, they’re selling for six, seven-figures, but the very top artists from the continent and they’re selling for €100,000 maximum, and that’s someone like Yinka Shonibare.” The few artists that do sell at that level, she points out, are being represented by galleries in in London, Paris or New York.

“In order to shape the narrative, we, as African galleries, have to turn up at these fairs, we have to compete,” Kola-Balogunsays. “Right now, we’re talking about repatriation of art from the colonial era, but a we’re also seeing a similar thing—galleries from Africa are not really being represented on an international stage, but African work is being taken abroad. It’s not the foreign galleries fault, it’s our fault because we’re not sufficiently investing in our own art. If we’re not careful, we’re going to see a repeat of history, we’ll be talking about repatriation of contemporary African art in a few centuries time.”

The sensitive debate surrounding the return of (often looted) cultural heritage via the so-called Macron Report and the current Western buying of contemporary African art cannot be directly compared, of course.

But some parallels are still valid. “Obviously, this is completely different—most of those older pieces were stolen by the west—these works are being bought legitimately,” El Glaoui says. “But it’s still a problem because African collectors have to buy now before it is too late, and they realise that they missed the chance to buy when their artists are still affordable.”

Seydou Keïta's Sans titre (MA.KE.001 BOX-NEG.00126), 1956-1959 ©Seydou Keïta/SKPEAC Courtesy: CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection & Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris/Brussels

Most of the work at 1-54 Marrakech is priced between the low thousands and around £50,000—though Goodman Gallery from South Africa is selling a William Kentridge work on paper for €120,000. To pay a foreign gallery in Moroccan dirhams is still a lengthy process, hence most works are priced in euros, pounds or dollars—El Glaoui would like to see the process simplified to encourage more Moroccan collectors.

Photography proves a unifying thread through both the fair and the many projects taking place around Marrakech this year as part of the fair’s public programming. Goodman Gallery is showing photographs by Shirin Neshat and David Goldblatt, and photography—particularly portrait photography—is a particular strength at the fair. The French gallery Galerie Nathalie Obadia has concentrated solely on photographic portraits exploring African identity, by artists including the famous Malian photographer Seydou Keïta and Youssef Nabil from Egypt, but also the US artist Andres Serrano’s depictions of African women.

Omar Victor Diop's Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (2014) from his Diaspora series © Omar Victor Diop Courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris.

As El Glaoui says, this is the city of Hassan Hajjaj, a London-born photographer with a cult following who splits his time between the UK and Morocco. At Comptoir des Mines, a gallery in Marrakech, he is showing works by a group of young Moroccan photographers—some as young as 18—including Yoriyas, a former break-dancer whose documentary style floor-shot work was recently bought by the fashion house Hermès.

Hajjaj describes the photography scene in the country as “very exciting”, attributing the upsurge of young photographers in the country to its accessibility as a medium, largely thanks to smartphones: “Everyone has mobiles, it’s the quickest way of expressing yourself. I’ve discovered a load of young, 18-19 year olds, doing photography.” The problem, however, is that “although photography is pretty huge across Africa, there are not enough gallery spaces, not enough magazines, not enough education [about it]” Hajjaj says. “I’m trying to show the gap, hopefully someone can take this on further than me. If I had the money or the team, I’d love to open a gallery and a school.”

Social media has been instrumental in the visibility of young African artists—Hajjaj sees young Moroccan photographers selling their work on Instagram. It also makes them more worldly, he says: “What I like about this new body of work being produced by young artists is that it is totally not Moroccan. There’s an expectation for Moroccan artists to be working in a certain way. But they are really pushing themselves to go somewhere else.” Why is that? “I would say it’s to do with this” he says, brandishing his iPhone. “Because they have the world in their hand.”

Of the current spotlight on African art, Hajjaj is heartened but cautious. “We don’t want it to be a trend,” he says. “From the West’s point of view, before this it was the Middle East, before this China…this can become dangerous, as it can move onto something else.” But, he says, “there’s definitely something happening with things like 1-54, young artists see this [buzz] and it makes them quite hungry.” Is it sustainable? “Not totally, but it’s getting there. More and more artists are making a living out of their work,” he says.

On the difference that 1-54 has made to the Marrakech scene in a year, Hajjaj says: “It’s too early to say. This takes time. I think 1-54 still has to settle. It’s a very small art fair. It goes back to finance and confidence.” With somewhere like Frieze LA, more galleries are willing to take a risk on a new fair, he says: “But this is Africa.”