Van Gogh was a friend of Emslie Horniman, whose family set up the Horniman Museum in south London. Although the link between them has never been recorded in the Van Gogh literature, they got to know each other in Antwerp while studying at the art academy.

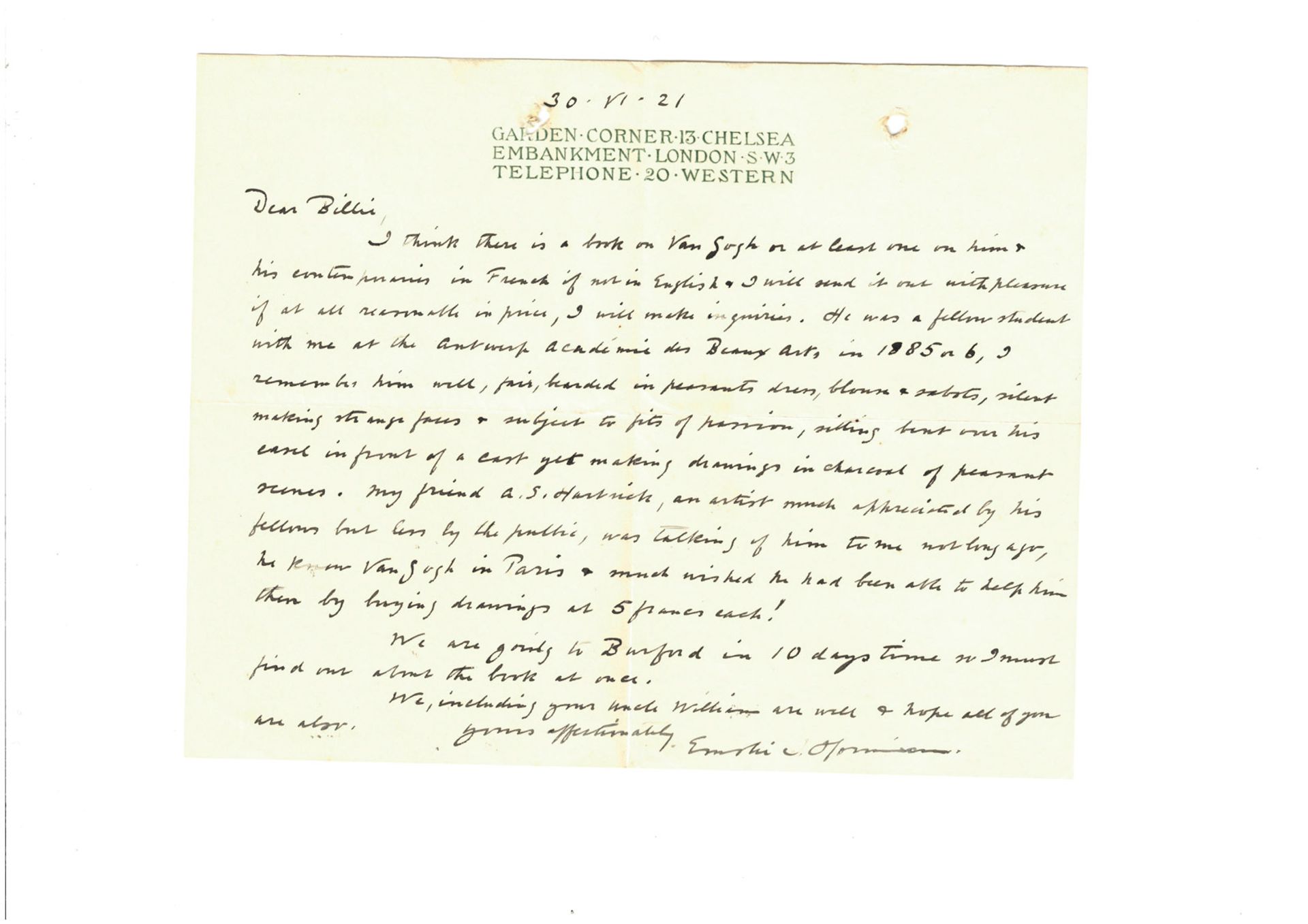

Emslie later reminisced about the Dutchman in an unpublished letter: “I remember him well, fair, bearded in peasant’s dress, blouse and sabots, silent making strange faces and subject to fits of passion, sitting bent over his easel in front of a cast yet making drawings in charcoal of peasant scenes.”

Letter from Emslie Horniman to William Plomer, 30 June 1921, Durham University Library (Plomer mss 324)

Van Gogh, aged 32, spent the winter of 1885-86 in Antwerp, hoping to improve his technique at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts. He had come from his parents' village of Nuenen, in the south of the Netherlands, after spending two years drawing and painting the peasantry. Although it is unlikely that Van Gogh wore farmer’s clothing in Antwerp, he was a notoriously shabby dresser. Emslie recalled that the stone floor of the academy was cold in winter, so Van Gogh wore knitted grey socks to keep his feet warm.

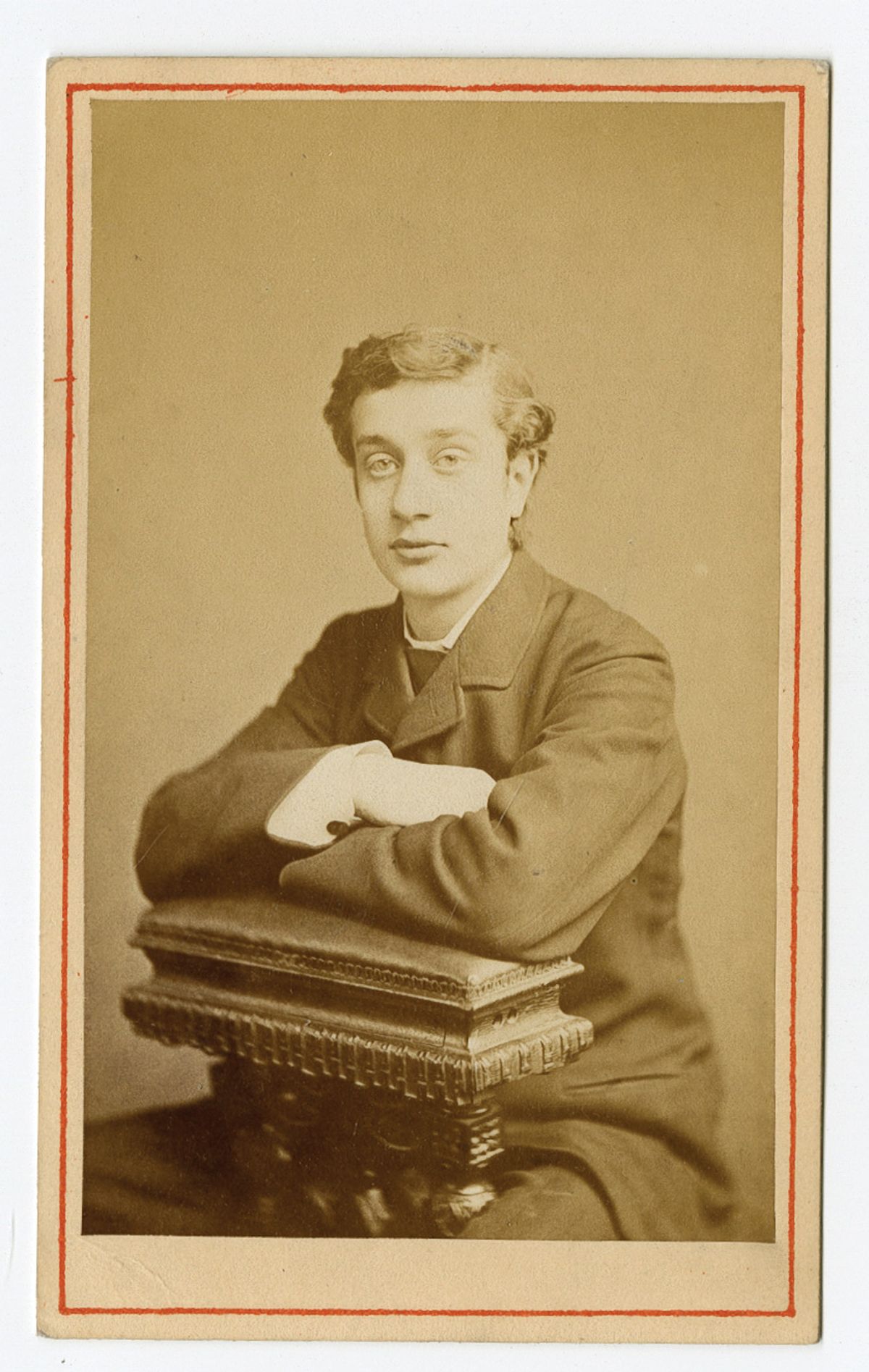

Emslie, aged 22, had gone to the Antwerp academy to train as an artist. He was the son of Frederick Horniman—a great collector of “curiosities”, ethnography, art and natural history. This wealthy family owned the Horniman company, then the world’s largest tea distributor.

Emslie’s memories of Van Gogh are recorded in two letters to William Plomer, a poet and nephew of his wife Laura. These 1921 letters are now in the archive of Durham University Library. In the second letter, Emslie wrote that Van Gogh was “subject to violent passion & seldom spoke”. He worked “very rapidly in charcoal, looking steadfastly at the plaster cast of an antique figure & then at a great pace making a strong & black drawing of say a landscape with peasant figures in a storm”.

Emslie added that his fellow students thought Van Gogh was “mad & were in awe of him & his work was so strange”. Although this letter is mentioned in Plomer’s 1975 autobiography (p. 115), it has not been cited in the Van Gogh literature.

Dermond O’Brien, The Fine Art Academy, Antwerp, 1890, National Museums Northern Ireland © National Museums NI

According to Emslie, their teacher at the academy got “very annoyed” with the Dutchman, but “recognised his talent”. The drawing classes were led by two Belgian artists, Eugène Siberdt and Frans Vinck. We know a bit more from Vincent’s letters to his brother Theo. Two weeks after joining the class, Siberdt “definitely tried to pick a quarrel with me today, perhaps with a view to getting rid of me”. Van Gogh explained that “the issue behind it is that the fellows in the class are talking about things in my work among themselves”. Siberdt must have had second thoughts, since a week or so later he apologised, saying that Van Gogh had “a good understanding of drawing and that he’d been rather too hasty”.

Van Gogh, who found the traditional teaching stifling, spent only six weeks at the Antwerp academy. The atmosphere in its studio is well expressed in a painting by the Irish artist Dermond O’Brien. Van Gogh then headed off to Paris, where he discovered Impressionism.

The Hornimans in the Ethnographical Saloon of the museum in their house, 1891. Frederick, who founded the museum, is second on the left, with Emslie behind him © Horniman Museum and Gardens

After his Antwerp training, Emslie travelled the world, visiting Egypt, central Africa, India, the Dutch East Indies and Japan. He abandoned painting, initially becoming an anthropologist and later going into politics as a Liberal Member of Parliament. His father, Frederick, had opened a museum in their London house in 1890 and in 1901 he established a purpose-built museum on the site, in south London’s Forest Hill. Emslie died in 1932, donating part of his personal collection to museums through what is now called the Art Fund. Sadly, there were no Van Goghs.