“The strength of Ruppersberg’s work is that it has managed to be accessible through references to American vernacular and literary histories while also being of a hardcore conceptual bent,” says Aram Moshayedi, the curator of the Hammer Museum’s retrospective dedicated to the hometown hero Allen Ruppersberg: his first comprehensive one in the US since 1985, when a mid-career survey was mounted by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. (This exhibition debuted at Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center in 2018.) While 1960s Conceptual artists in New York, London and Europe tended to approach language from a philosophical or Structuralist position, Ruppersberg was always more interested in literary fiction, screenwriting and poetry—not to mention wry humour.

Born in 1944, Ruppersberg has long been a mythical presence in the Los Angeles art world—which was perhaps his intention. “Evasion has always been part of his work,” Moshayedi says. The artist once listed his influences as “youth, serial killers, magic, movies and film history, Raymond Roussel, reading and looking, fate, suicide, the fountain of youth, surrealism, fiction and reality, high and low cultures, hell, Hollywood, Bible stories and horrific current events”. Over the past five decades he has pursued these interests quietly, often seemingly from the margins, operating from rented offices and moving frequently between California, New York and Europe. Where’s Al? (1972/2006) is the title of an early installation of typed index cards and photographs, a landmark piece included in this show.

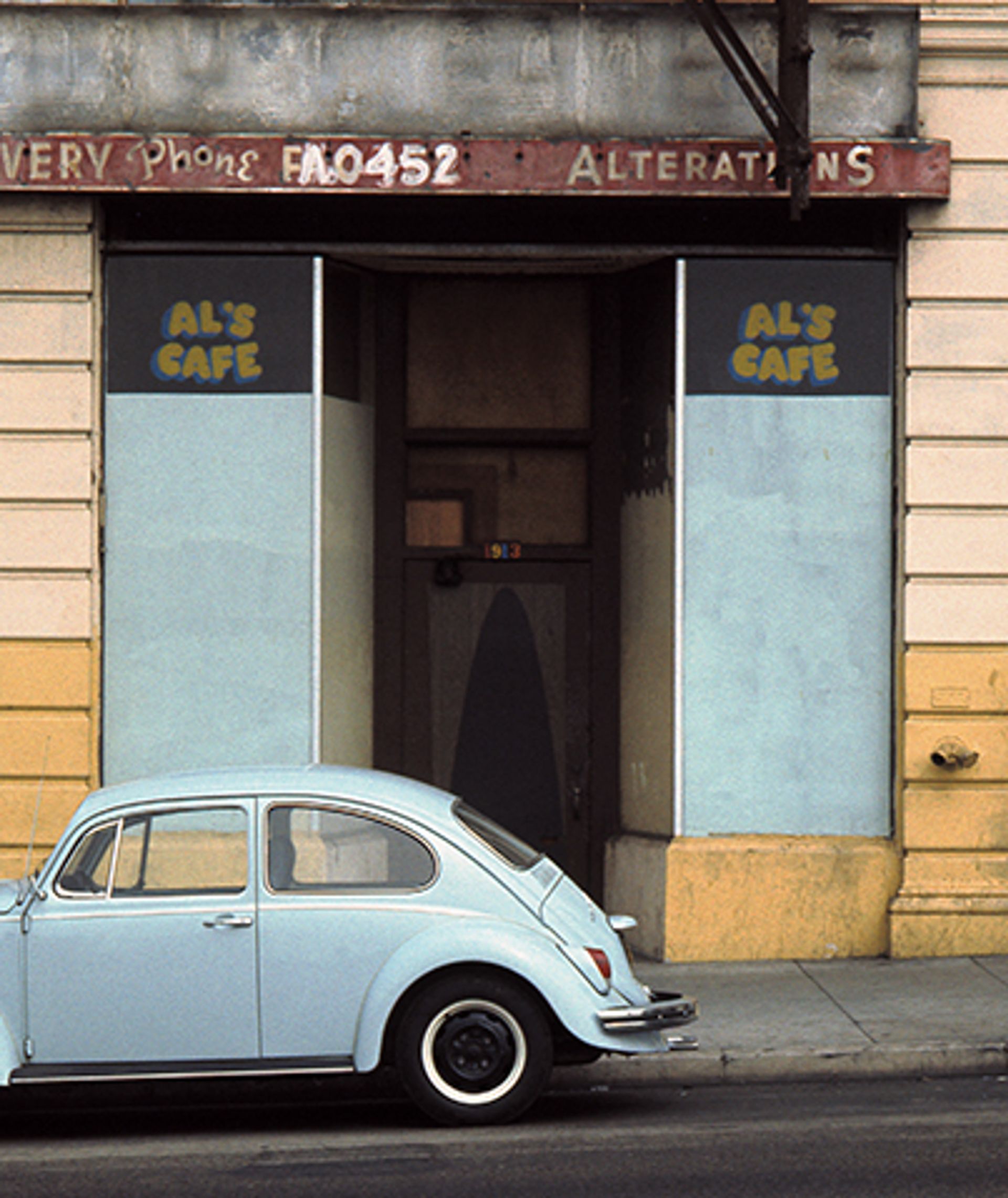

Allen Ruppersberg's Street view and façade of Al's Café at 1913 West 6th Street, Los Angeles (1969) Courtesy of the artist, Greene Naftali, New York and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles; Photo: Gary Krueger.

Ruppersberg got off to an auspicious start. Soon after graduating from Chouinard (now CalArts) in 1967, he was invited to participate in Harald Szeemann’s legendary exhibition, Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, held at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1969. Ruppersberg did not travel to Switzerland because he was working on a project in a storefront in downtown Los Angeles. Part installation, part participatory performance, Al’s Café (1969) was a short-lived enterprise that, while it looked much like any other American diner, served dishes listed on the menu as “three rocks with crumpled paper wad” ($1.75) or “simulated burned pine needles à la Johnny Cash, served with a live fern” ($3.00). The Hammer’s iteration of Intellectual Property (1968-2018) boasts the only full set of dishes from Al’s Café, a recent gift from the family of collectors Stanley and Elyse Grinstein, and too delicate to travel to Minneapolis.

While on one level Al’s Café was an irreverent way of disseminating assemblage sculptures parodic of Land Art, in another it was a social sculpture, bringing together interested participants and generating discourse around an event. It preceded the Relational Aesthetics of Rirkrit Tiravanija and Thomas Hirschhorn, for example, by a quarter of a century; in the 1990s, Ruppersberg was latterly celebrated as a progenitor of the movement.

While Ruppersberg is often physically and conceptually central to his projects, he always seems to stand just out of shot. Described by Siri Engberg, the curator of the Minneapolis show, in her catalogue essay as his “most ambitious self-portrait”, The New Five Foot Shelf (2001) is a room-sized installation of books and posters that reproduce, on one-to-one scale, Ruppersberg’s former New York studio. A major new 13-hour video debuting at the Hammer, Over and Over, Again and Again (2019)—a collaboration with Thomas and Lucas Cvikota—collates images of an anonymous record collector’s typed index cards, accompanied by audio recordings from Ruppersberg’s own collection. Sound and image may or may not relate; Ruppersberg remains an elusive presence.