As part of the fourth and final phase of its 15-year, £80m revamp, the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh has unveiled Ancient Egypt Rediscovered, a new gallery for its beloved Egyptian collection. Conservators and curators have spent four years preparing displays that span more than 3,000 years of history, including many objects that have not been seen in generations. Margaret Maitland, the senior curator of the museum’s Ancient Mediterranean collections, tells The Art Newspaper about some of the highlights.

Coffin of the “Qurna queen” (around 1585BC-1545BC): The new gallery will play to “a strength of the collection” with several burial assemblages that are “like a snapshot in time”, Maitland says. Chief among them is the Qurna burial group, discovered in 1908 by Flinders Petrie, the “father of Egyptian archaeology” at Qurna, Thebes. The burial is fascinating because it dates from the late 17th or early 18th dynasty, an era of political turmoil that is “one of the least understood by Egyptologists”, Maitland says. The identity of the two mummies—a young woman and a child aged two or three—found in the “simple pit grave” remains unclear. The child’s coffin sat on top of the woman’s, abrading the hieroglyphs of her name from the wooden surface. But the elaborate polychrome style of the woman’s coffin suggests she was of high status and possibly a member of the royal family at Thebes. She is known by some Egyptologists as the “Qurna queen”. If this were confirmed, it would give Edinburgh the only intact royal burial group outside Egypt. © National Museums Scotland

Qurna gold jewellery: The “Qurna queen” was buried with elite grave goods including “eggshell-thin ceramics from Sudan” and “an incredible array of gold jewellery”, Maitland says. Scientific analysis of the jewellery has shown that some items have “extremely high levels of purity”—a rarity for this period, since “gold refining was thought not to have been introduced [in Egypt] until the Roman era”. They include earrings that were “quite fashion-forward” for the time, a well-worn electrum girdle worked “by at least two separate craftsmen” and a necklace comprising 1,699 gold ring beads (Petrie slightly under-counted them). “When we showed some of the jewellery to a master goldsmith, he was completely astonished at the level of skill,” Maitland says, citing “near-invisible joins” in the soldering. There had also been “a conscious effort” to create a set of matching jewellery for the child, most likely her daughter. © National Museums Scotland

Coffin of a child, Tairtsekher, daughter of Irtnefret, possibly from Deir el-Medina (around 1292BC-1200BC): Although much of modern Egyptology is based on the study of elite tombs, the new gallery aims to “make Egypt more relatable” and also displays “objects that tell us about other members of society”, Maitland says. One vitrine looks at the craftsmen of Deir el-Medina, who for almost 500 years built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings and applied that skill to their own burials as well. This early 19th dynasty coffin in plastered and painted wood, was “very rare and elaborate for a child”, Maitland says. © National Museums Scotland

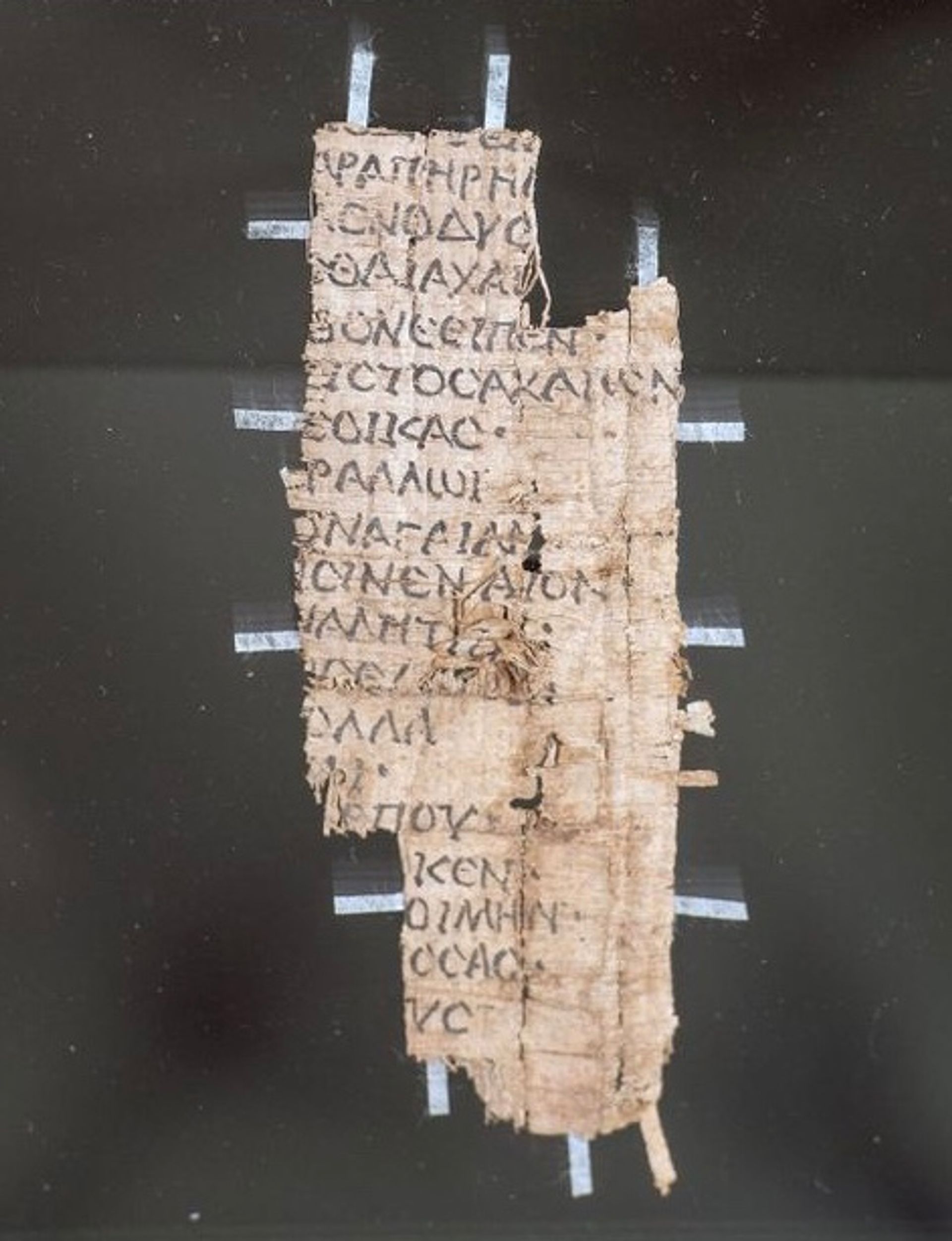

A schoolboy's copy of Homer's Odyssey (around 30BC-AD395): Another display case focuses on a Roman town called Oxyrhynchus, “home to one of the richest discoveries of ancient Egyptian papyri”. Maitland singles out this fragment of a trainee scribe’s copy of Homer’s Odyssey. The text comes from “the part where Odysseus is spinning the tale of how he was a pirate on the Nile, so of course it would have been of interest to a Roman schoolboy in Egypt”, she says. © Neil Hanna/National Museums Scotland

Stela fragment with depiction of Akhenaten (around 1356BC-1292BC): Nefertiti’s husband Akhenaten was an “extremely controversial” pharaoh who sought to transform ancient Egyptian religion in the 18th dynasty. He abandoned the old gods to worship Aten, the disc of the sun (rather than the falcon-headed sun god Ra). “After his reign, the Egyptians destroyed all the monuments he built and tried to erase his name,” Maitland says. “So the stela that we have was excavated in a number of fragments and the figure of Akhenaten himself doesn’t appear to have survived.” His name was “purposefully chiselled out of the monument” and the “reddish” part of the stone indicates it was also burned. © National Museums Scotland

Coffin of the “Qurna queen” (around 1585BC-1545BC): The new gallery will play to “a strength of the collection” with several burial assemblages that are “like a snapshot in time”, Maitland says. Chief among them is the Qurna burial group, discovered in 1908 by Flinders Petrie, the “father of Egyptian archaeology” at Qurna, Thebes. The burial is fascinating because it dates from the late 17th or early 18th dynasty, an era of political turmoil that is “one of the least understood by Egyptologists”, Maitland says. The identity of the two mummies—a young woman and a child aged two or three—found in the “simple pit grave” remains unclear. The child’s coffin sat on top of the woman’s, abrading the hieroglyphs of her name from the wooden surface. But the elaborate polychrome style of the woman’s coffin suggests she was of high status and possibly a member of the royal family at Thebes. She is known by some Egyptologists as the “Qurna queen”. If this were confirmed, it would give Edinburgh the only intact royal burial group outside Egypt. © National Museums Scotland

In Pictures: Egyptian treasures at the revamped National Museum of Scotland

Senior curator Margaret Maitland reveals the stories behind some of the key exhibits in the new Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery

Assistant conservator Bethan Bryan works on a coffin from the Qurna burial group © National Museums Scotland