With its colourful swirling fabric panels, the African Yorùbá masquerade costume known as the egúngún mask is both a potent symbol of belief and a source of entertainment. Worn by a ritual performer to summon and honour the spirits of ancestors, it testifies to a family’s wealth and design sense, with each of the textiles adding a layer of nuance and status.

For Kristen Windmuller-Luna, a curator of African art at the Brooklyn Museum, the costume has also been a brain-teaser of sorts, posing stubborn questions about provenance and history. After joining the museum last April, she began a research project on the egúngún costume, which entered the collection as a gift in 1998. She wanted to find out as much as she could about its origins with the goal of showcasing it in her first exhibition. One: Egúngún, part of a series of shows that each centres on one object in the museum’s collection, is set to open on Friday (8 February).

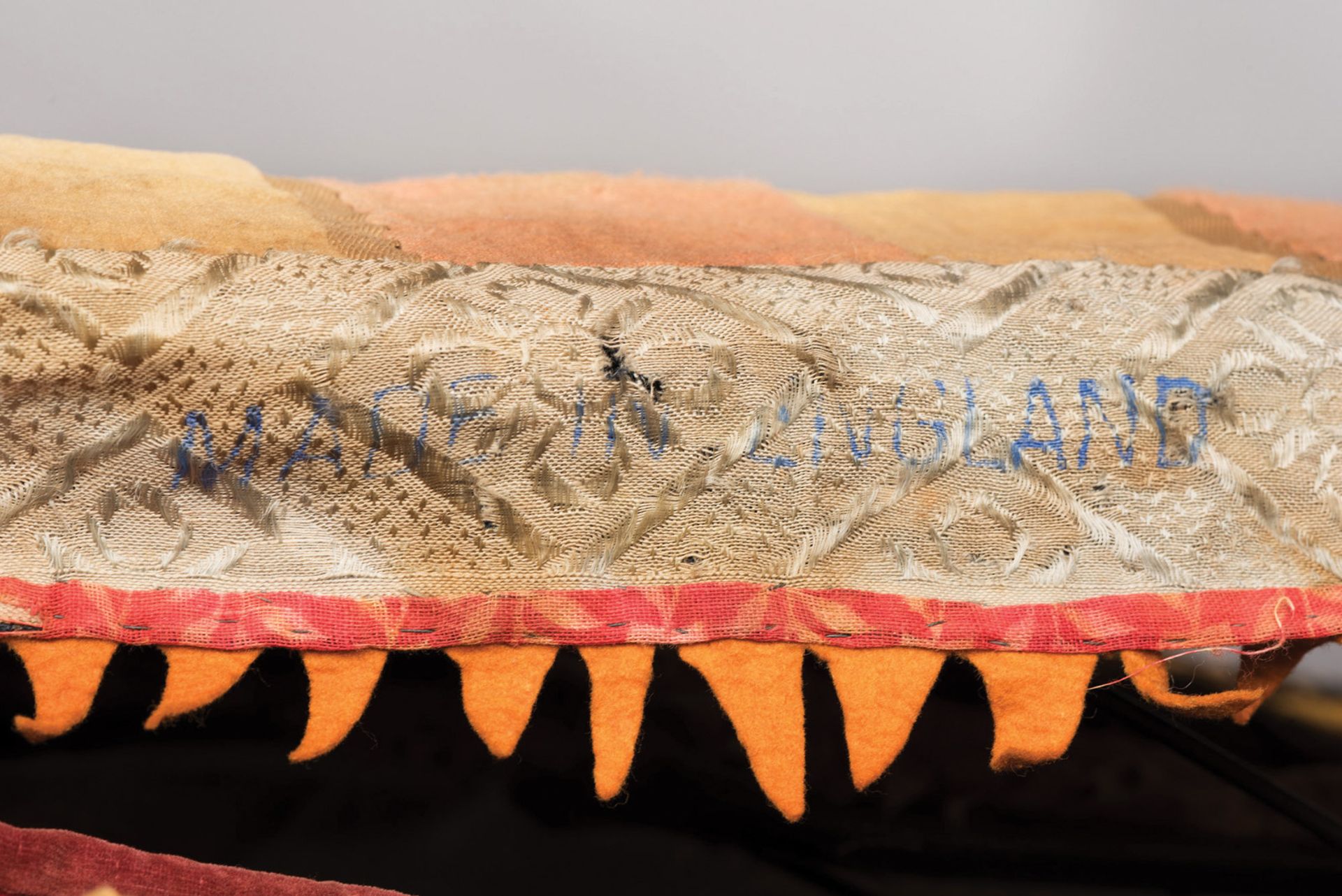

Judging from its type, a “paka” egúngún, Windmuller-Luna says, the costume clearly was sewn together by Yorùbán tailors in south-western Nigeria, most likely in Oyo state. (The textiles are attached to a plank of wood with a doughnut-shaped coil of fabric that rested on the performer’s head.) Aided by conservators at the Brooklyn Museum, she proceeded to diagram the costume and to photograph each of its 300-plus textiles, identifying fibre types, weaves and decorative techniques, as well as markings such as “made in England” or “made in India” and selvedge marks. The team traced the fabrics to a panoply of countries in Africa, Europe and Asia.

Windmuller-Luna also delved into the Yorùbá notion that both cloth and human beings are immortal, with the cloth sometimes enduring as mere fragments. “Just as cloth wears to shreds, the living are transformed through death into a state of immortality,” she says. She describes the egúngún costume as “an exceptional visualisation of this really powerful theorising”.

Windmuller-Luna concluded that the very earliest the costume could have been made was 1920, based on the identification of a vivid print fabric in orange, black and white that was made that year by the Dutch textile company Vlisco for the West African market. It is unclear whether the piece of fabric in the egúngún was made by Vlisco or by a copycat brand.

A fabric strip including synthetic fabrics such as rayon and viscose that is part of an egúngún mask at the Brooklyn Museum. Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum

Divination ceremony

She then travelled to Nigeria to interview art historians, contemporary artists and textile experts about the costume’s probable origins, including the source of each fabric. Her trip paid off: D.O. Makinde, a professor of art history, ultimately led her to the clan that created the costume, the Lekewogbe family in the south-western city of Ògbómoso.

Armed with a video camera, Windmuller-Luna interviewed two elders in the family who said their grandfathers had told them that the costume had been stolen from a shrine in the family compound in 1948. (As a result, the Brooklyn Museum now dates the costume’s origin to sometime between 1920 and 1948.) “I asked them: ‘Is this appropriate to be on view? Are you all right with this exhibition? Do you want the work back?’,” she says.

The elders, Yemi Ajoke Koseemani Sakora and Fajimi Adesoye, replied that they would have to turn to a god, Orúnmìlà, for answers through a Yorùbá divinatory system known as Ifá. Accompanying them and other family members to a shrine room in the family’s compound, Windmuller-Luna took part in a divination ceremony through which the family asked: “What was the meaning of my visit—was it something positive? Did we have blessings for this [exhibition] project?” Reciting prayers and posing questions, she says, the family members poured gin on their current egúngún costume, a successor to the one that was stolen, and sipped from a communal cup of gin and tossed kola nuts that broke into pieces on the floor. A babaláwo, or diviner, interpreted the patterns into which the nuts fell.

The verdict: the Brooklyn Museum was free to proceed with the exhibition of the costume, which was no longer “spiritually empowered”.

The Lekewogbe family’s current egúngún is described by the family as the “son” of the one in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection. Whoever took the original left the long socks that accompany the costume behind, the elders told Windmuller-Luna, which the family then used in a ceremony to inaugurate its new egúngún. “The long socks were still considered spiritually empowered or sanctified,” she says, "and they used them to sanctify a new mask." The successor costume, more slender with a large headpiece studded with cowrie shells, is called Fotiweri, or “He who walks with gin”.

The Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition will include a photograph of the successor egúngún, as well as video footage of Windmuller-Luna’s interviews with the elders and with Nigerian art and textile experts. It will invoke the ongoing role of the egúngún in Yorùbá festivals organised in the US, featuring a text contribution from Chief Ayanda Ifadara Ojeyimika Clarke, a leader of the local Brooklyn Yorùbá community, whom Windmuller-Luna consulted during the planning of the exhibition. Four other West African textiles and garments will be on display to highlight the importance of cloth in the Yorùbá belief system. And there will be text and labels in both English and Yorùbá, to underline that the Yorùbá words and names “have worth and meaning”, the curator says.

The goal, Windmuller-Luna says, is to wrap multiple sources and perspectives into the show, and to celebrate how the egúngún “is both part of Yorùbá history and a vibrant part of its present, whether in Nigeria or here in Brooklyn”.

Detail of a strip of fabric made in England that is part of the egúngún costume at the Brooklyn Museum © Brooklyn Museum

Community involvement

The issues of community involvement and inclusiveness are pressing for the Brooklyn Museum, which drew criticism for appointing Windmuller-Luna, who is white, as its curator for African art. An activist group known as Decolonize This Place called it a “tone-deaf decision” and said that it was offensive to “the diverse communities of Brooklyn”. It called on the museum to create a “decolonisation commission”.

Asked if her intense consultation with Nigerian and local sources could be seen as a rejoinder to such critiques, Windmuller-Luna says: “I wouldn’t go that far, because this is the way in which I have always worked. And this is the way in which good curatorial practice is done. Communities of origin, both in the diaspora and on the [African] continent, are incredibly important, and are always a part of your work.”

Windmuller-Luna emphasises that her research into the egúngún continues, as she studies costumes in other museum collections and tries to determine whether there are shared fabrics or types of fabric. She is eager to know more about the object’s whereabouts between 1948 and 1998. And she is exploring potential collaborations between the Brooklyn Museum and the Nigerian National Museum in Lagos.

The very existence of the exhibition will open new doors, she predicts. “These are things where you keep on going and the trails of breadcrumbs usually lead to something,” Windmuller-Luna says. “Persistence is always so important.”

• One: Egúngún, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 8 February-18 August