As the first of a glut of exhibitions celebrating the bicentenary of John Ruskin’s birth opens at Two Temple Place in London, the latest podcast from The Art Newspaper explores the life and work of this complex polymath. Robert Hewison, the author of numerous books on Ruskin, the most recent of which is Ruskin and his Contemporaries, tells us about his the breadth of his achievement, from his art criticism and architectural studies to his social campaigning, and his huge influence on artists, writers and thinkers across the world.

But in terms of those who influenced Ruskin, no one was more important than the British artist J.M.W. Turner. Hewison describes how Ruskin’s passion for Turner’s work was founded in his relationship with his father, also called John, who made his fortune as a sherry merchant but had a deep interest in art and literature. “He poured a lot of his own ambitions into his son, John Ruskin,” Hewison says. “So that, for instance, the father would encourage the son by paying him a penny a line when he wrote poetry as a boy and he paid for the very best drawing masters.” He adds that one of their shared interests was collecting art. “The art they collected wasn’t aristocratic art, it was what we now think of as the picturesque, that is to say rather pleasant scenes of crumbling cottages and mountains and all those things. It’s a very English watercolour taste; they didn’t really go in for oils and things like that.”

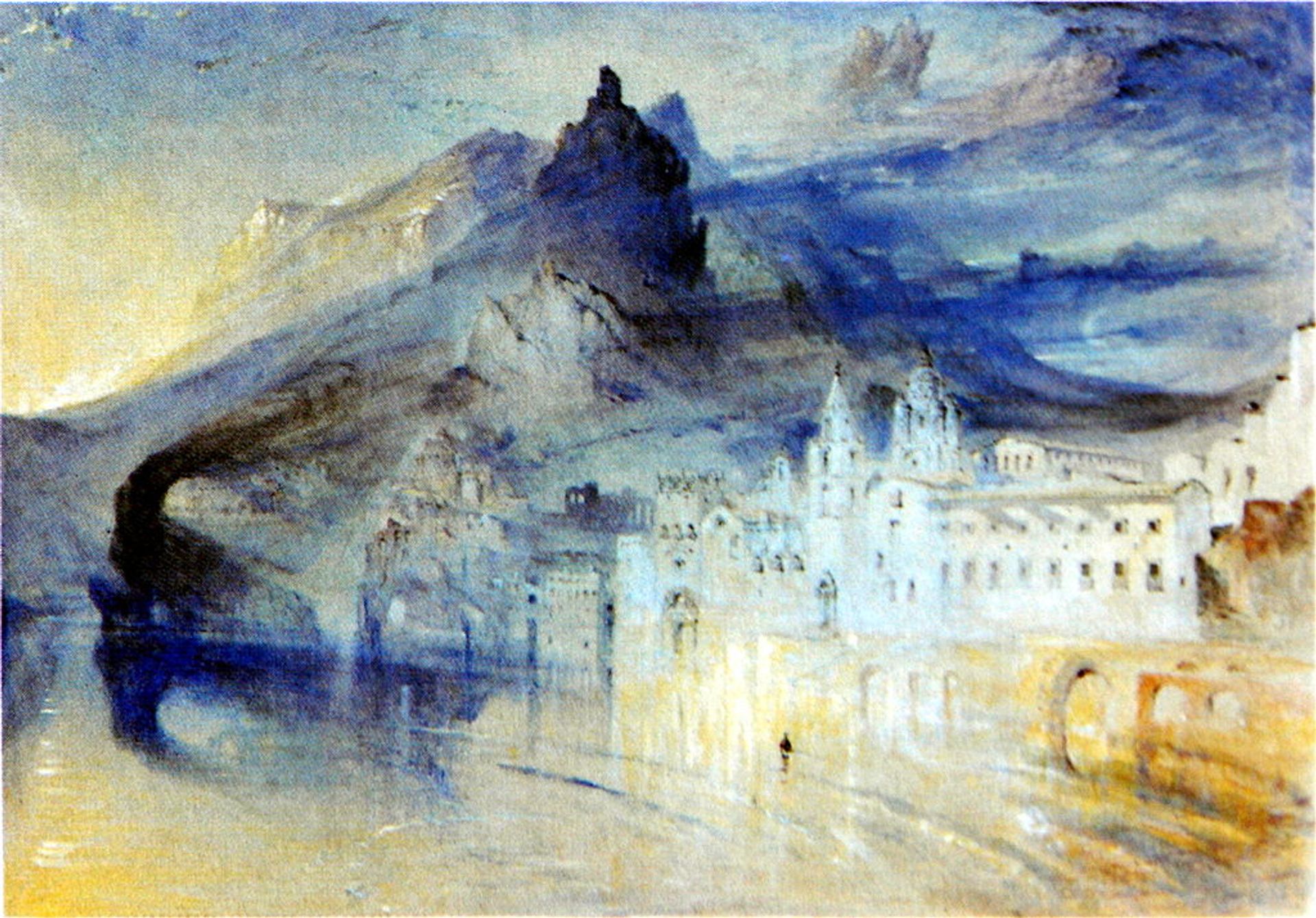

Some of Ruskin's watercolours are so accomplished they can be mistaken for TurnersRobert Hewison

Turner, of course, was the greatest watercolorist of his age. “Ruskin and his father actually employed Turner, in the sense that they commissioned work from [him]. And so you get this very interesting relationship… a young, very sensitive, pretty neurotic young man, deeply admiring this curmudgeonly old artist. Because Turner was 30 years older than Ruskin.” And Ruskin witnessed Turner “literally at work”, Hewison says. “Turner would show him the sketches, and say: ‘What do you think of this, would you like me to work this up into a finished painting?’ And Ruskin would see the imaginative processes.”

Ruskin first wrote about Turner aged just 16, when the master’s experimental work was being savaged by critics in the 1836 summer exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts: he wrote a defence which his father sent to the artist. But Turner did not want it published, and it only appeared after Ruskin’s death in 1900. “But this was the point at which Ruskin found his vocation, which was to use his literary talent to make visual art something of great importance.”

John Ruskin's View of Amalfi (1844) Photo: via Wikimedia

Crucial to Ruskin’s perceptiveness was his own artistic ability, even though he never called himself an artist. “The important thing about Ruskin was that because he was an artist, he applied a form of criticism that is unusual, in the sense that he actually drew and analysed himself. So Ruskin, in a sense, discovers his own capacities as an artist through pastiche, by copying Turners.” Some of Ruskin's watercolours are so accomplished they can be mistaken for Turners, Hewison says.

Turner was at the heart of one of the most notorious stories in British art history, which has coloured Ruskin’s reputation: the supposed burning of Turner’s erotic drawings at a horrified Ruskin’s behest. “What actually happened is that after Turner died in 1851, all his works were left in the basement of the National Gallery, gathering dust until Ruskin came down and started sorting them out,” Hewison explains. “And while he was sorting them out he came across a package of drawings, some of which I suppose you could call pornographic. But most of them are life studies and things like that. The story got about, partially because Ruskin wrote a letter saying he’d done it, that these drawings were put to the match. But in fact they weren’t, because if you go to the Tate you can see all these drawings; when I did a show in 2000 for Ruskin’s centenary [Ruskin, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites at Tate Britain], we showed these drawings.”

Hewison argues that Ruskin said the letters had been burned to protect Turner’s reputation, partly as this was happening around the time that the Obscene Publications Act was passed in Britain. But it also undoubtedly reflected Ruskin’s difficulties with erotic material, and his awkwardness about sex—famously his marriage to Effie Gray was annulled because it was not consummated. “Ruskin was pretty innocent and certainly his encounter, I think, with Turner’s erotic side was a problem for him, simply because Turner was such a hero,” Hewison says. But he adds that what Ruskin might have seen as Turner’s “dark side” is trifling by modern standards: “they’re not particularly shocking drawings at all”.

By Turner’s death, the two had fallen out, Hewison says—indeed, Ruskin described Turner’s 1846 painting Angel Standing in the Sun as being “indicative of mental disease”. The further disillusionment when he went through the Turner Bequest, may not have been limited to Turner’s taste for erotica. “There is another argument,” Hewison explains, “that says that Ruskin, when he went through absolutely everything that Turner had done, thought rather less of him, because he saw all the work—and he could see, for instance, that, ironically, Turner’s figure drawing is hopeless.”

You can hear the rest of the interview on The Art Newspaper podcast, in association with Bonhams, which you can also find it on iTunes, Soundcloud and TuneIn, or wherever you usually listen to podcasts. This episode also includes a discussion of E.H. Gombrich, the great art historian.

- Ruskin and his Contemporaries, Robert Hewison, Pallas Athene Publishers, 412pp, £59.99 (hb and pb)

- John Ruskin: the Power of Seeing, Two Temple Place, London, until 22 April; Millennium Gallery, Sheffield, UK, 29 May-15 September.

- You can see a comprehensive list of the anniversary events at the