For more than 40 years, the provocative photomontages of Linder Sterling, known simply as Linder, have been whipping up strong reactions. She came of age in the underground punk and post-punk scene of late 1970s/early 1980s Manchester, where she shared a flat with the Buzzcocks’ then frontman Howard Devoto and formed a lifelong friendship with the Smiths’ singer Morrissey, who described her work as “screams”. It was at this time that she changed her name and took up the scalpel, making photomontages that often combined images sliced from pornographic magazines with pictures taken from homeware and gardening catalogues. In recent years she has become a leading figure in British art. Solo shows at the Hepworth Wakefield and Tate St Ives in 2013 were followed by an invitation last year to be the first artist-in-residence at Chatsworth, as well as a film and banner commissioned for Glasgow Women’s Library and a major exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary. Linder’s first solo show in London since 2011 opens at Modern Art this month and an 85m-long photomontage accompanied by posters and a tube map for Southwark Underground station in London remains in situ until November. A retrospective opens at Kettle’s Yard Gallery in Cambridge in February 2020.

The Art Newspaper: You’ve recently been working on a large scale, but your Modern Art show finds you scaling back to the smaller photomontages for which you are best known.

Linder: To come back inside the cocoon of the white-walled gallery and show new and recent works that are relatively modest in scale feels very refreshing. I see the work I do as acting as biopsies—whether it’s taking from interior furniture design magazines and trying to match them up with the pattern magazines for women, or pairing the flowers from a rose catalogue with pornographic images. I try to cross-fertilise and bring together juxtapositions of desire and consumption in the same frame. Like Mary Shelley, I’m seeing what monsters can be made.

The Modern Art show opens with what you call a “prelapsarian room”, containing the recent Mantic Stain series, influenced by the automatic painting techniques of Surrealist artist and occultist Ithell Colquhoun.

In 1952, two years before I was born, Colquhoun wrote the essay Children of the Mantic Stain in which she lists ways of using what she calls “objective hazard” to generate marks on paper. So, you can have collage, you can have fumage, decalcomania, stain techniques and many more. This idea of having zero conscious control and throwing something in your way that can almost trip you up, so you can fall flat on your face, or gain enlightenment and great insight, showed how I might return to mark-making. Mantic in Greek means a state of divine possession, a slightly frenzied oracular, and there’s a gorgeous moment of letting go and thinking: “No, Linder, that’s the whole point: you really can’t control them.” It was so instantly pleasurable. It is the absolute opposite of the photomontage process. It’s about flow; an oracular flow, perhaps. I feel that with a lot of the work I make there has to be this kind of visceral thrill—it’s often not intellectual, it really is that sense of glee. And when it really works you squeal with delight.

How much was being involved in the punk scene in 1970s Manchester an influence on your trademark photomontages?

By the end of 1976 I had grown tired of my own mark-making, so I exchanged my pencils and paints for a surgeon’s scalpel and a tin of Cow Gum. In parallel, music in Britain had also grown tired and new sounds had emerged under the unlikely moniker of punk. I’d argue that punk was encoded with its own inbuilt obsolescence, which meant that there was only a relatively brief cultural moment in which to make one’s mark. That mark had to be swift, economic of means and instantly hit the target. None of us thought in terms of having access to studios, arts funding or gallery representation—the art world had yet to be born and christened. In Manchester we made work in bedrooms and bedsits, dependent upon two photocopy machines in the city to duplicate our work. I made a series of photomontages using images cut out from men and women’s magazines. The photomontages were postmortems of sorts, as much dissections of culture as they were hybrids emerging from it. Record sleeves were our galleries and posters our monographs.

There was a direct political aspect to your work with images of women at the centre from the beginning.

At the age of 16 I discovered Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch. I’d only known her before in a satirical Granada TV show called Nice Time with Kenny Everett. I discovered it in a small bookshop in Wigan—John Holmes’s cover fascinated me and the book changed how I saw life. I started taking images of women that mirrored every facet of social and sexual attitudes at the time. I just wanted to line them all up and parade them all. There was fashion, there was Woman’s Own, Family Circle, True Confessions, and then going through to pornography. I was taking images of women from wherever I could find and cutting out all these little figures and thinking, where do I put them? I wanted the idea of a biopsy as within seconds of cutting out, say, pornography, and transplanting it into a very exquisite interior, something quite shocking happens: the two just shouldn’t be together. Whether it’s pornographic imagery or fashion editorial imagery, they are like eggshells, they are all so fragile and carefully styled and constructed. It doesn’t really take much to knock them off.

From your involvement with punk and your famous Hacienda performance through to your recent work with ballet, performance and film, music and live work have been a parallel preoccupation to photomontage.

I remember performing at the Hacienda in Manchester 1982 and wearing a meat dress and a dildo—I felt a bit like a female astronaut being sent out into cultural space. But in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Manchester it was obligatory that you went on to the stage and you made some sort of sound, either with an instrument or your larynx. All the people around me were making great music, and the thing about punk was that anybody could get up there—it was incredibly democratic and that was good. Performance is quite often like an exclamation mark for me—it comes out and then I retreat again. Making photomontage is incredibly solitary; it’s just me, a glue stick and a pair of scissors. So I think that’s why at certain periods I have to animate and go into performance, otherwise I would just go stir-crazy.

• Linder, 'Ever Standing Apart From Everything', Modern Art, London, 1 February-16 March

Biography

BACKGROUND

Born Linda Mulvey in 1954 in Liverpool, Linder grew up in Wigan. In 1973 she enrolled at Manchester Polytechnic and took a degree in graphic design. “I felt it held the most promise for me aesthetically, sartorially and politically,” she says.

MILESTONES

In 1976 she went to a Sex Pistols, Buzzcocks and Slaughter and the Dogs gig and her life “changed forever”. She started to use a scalpel as a creative instrument—“I wanted to make stab incisions into the host culture around me.” She also Germanised her name to Linder. “Musically, sartorially and graphically we started to cut things up.” Linder’s 1977 collage was used for the cover of the Buzzcocks’ first seven-inch single, Orgasm Addict. She founded post-punk band Ludus in 1978, performing at the Hacienda in Manchester in 1982. Solo exhibitions of Linder’s work have taken place in New York in 2007, London in 2010 and Paris in 2013. For her solo shows at Hepworth Wakefield and Tate St Ives, also in 2013, Linder collaborated with Kenneth Tindall of Northern Ballet for a performance piece, The Ultimate Form. She was artist in residence at Chatsworth House in 2018. Also last year she opened a solo show The House of Fame at Nottingham Contemporary, as well as a flag and a film for the Glasgow Women’s Library and a billboard-sized work for London Underground, all entitled Bower of Bliss. Linder was awarded a Paul Hamlyn Award in 2017.

REPRESENTATION

Stuart Shave’s Modern Art, London; Blum & Poe, New York

Three key works

Linder, Bower of Bliss, 2018. Film still. Cinematographer Fatosh Olgacher Courtesy of Glasgow Women’s Library

Bower of Bliss, Glasgow Women’s Library (2018)

“Last year the Glasgow Women’s Library invited me to create their inaugural flag and an accompanying film,” says Linder. “At the same time, I was artist in residence at Chatsworth, where Mary Queen of Scots was once held prisoner. I became intrigued with Mary’s biography as a cipher for women’s creativity and ingenuity under times of duress. The Bower of Bliss was filmed in Queen Mary’s Bower at Chatsworth and the film is being looped in the foyer of the Glasgow Women’s Library for 12 months… a decompression chamber to help visitors pause as they enter and savour the moment. The flag depicts women’s mouths open wide to disseminate and receive. Bliss is a feminist issue.”

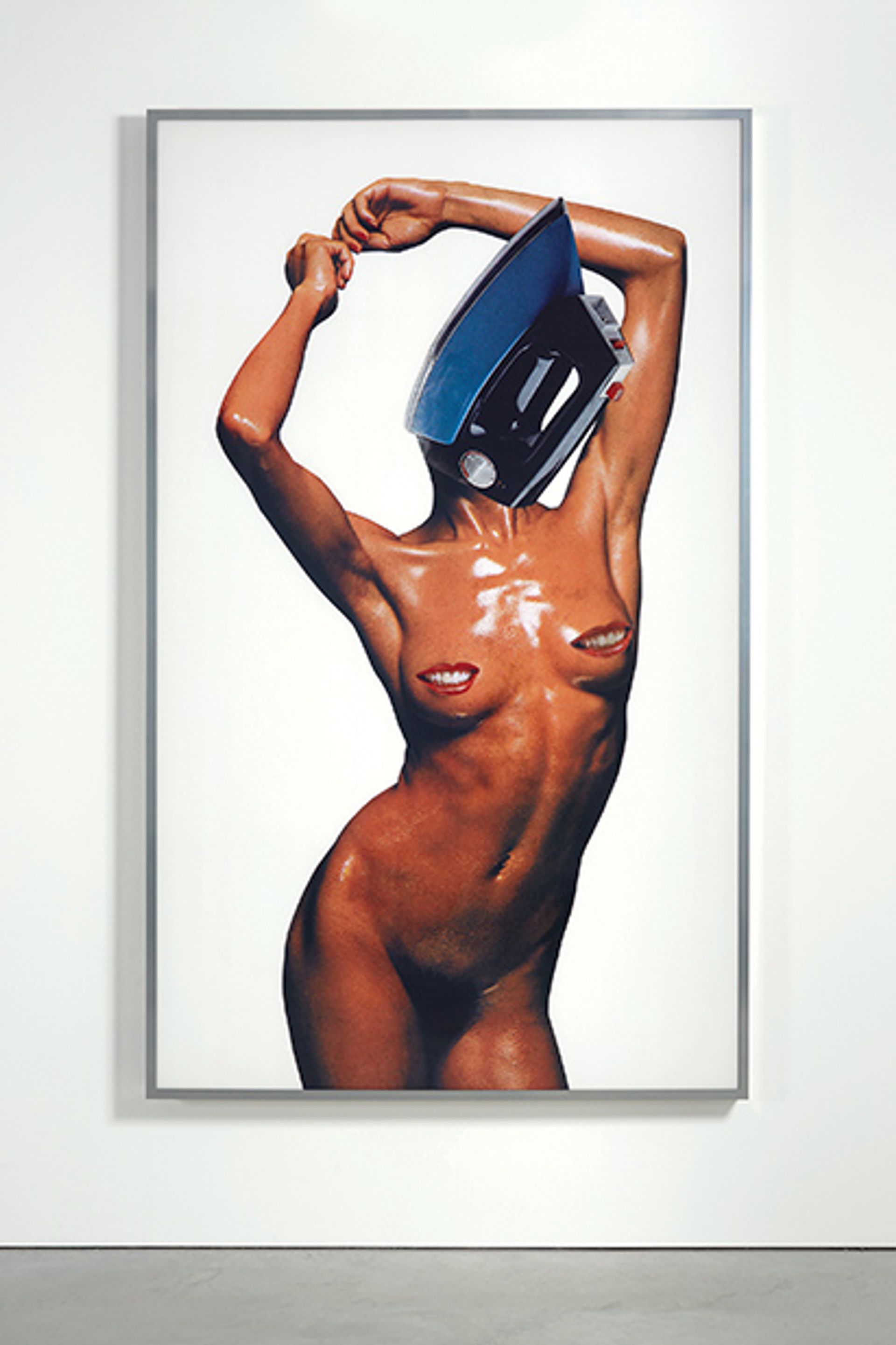

Linder, It's The Buzz, Cock! (2015) © Linder/Courtesy the artist & Modern Art, London.

It’s the Buzz, Cock! (2015)

This image was originally used in 1977 for the cover of the Buzzcocks’ first seven-inch single, Orgasm Addict. The BBC banned the single and United Artists refused to press it. “In 1976, a guitar solo of only two notes or two cut-outs of mouths stuck onto a pin-up delivered far more clout than their inverse,” Linder says. “This photomontage is pure Ovid with the Morphy Richards iron providing the perfect metamorphosis for punk’s Mona Lisa.”

Linder, Infant’s Door (2015) © Linder/Courtesy the artist & Modern Art, London.

Infant’s Door (2015)

In 2009 Linder remembers visiting the Barbara Hepworth sculpture garden in St Ives where she “fell in love with Hepworth’s work after a lifetime’s indifference”. Several years later, Hepworth’s sculptures inspired The Ultimate Form, a new work made in collaboration with Northern Ballet, and this series of photomontages uses fashion imagery and household appliances dating from 1970-75. “Barbara Hepworth remarked that she could speak through marble and I’m fascinated by the idea of the female artist as ventriloquist. This series of works ventriloquises fashion photography in the last five years of Hepworth’s life, when the female figure was often depicted wandering freely in the landscape while the accompanying adverts tethered her very firmly in the home.”