The Irish-born conceptual artist Michael Craig-Martin, who grew up in the US and studied art at Yale before moving to England in 1966, has generally been claimed as a UK artist. He has crossed the Atlantic for a rare US solo show, and the first to present such a range of work at the Gallery at Windsor, an exhibition space at an exclusive planned community in Vero Beach, Florida. Michael Craig-Martin: Present Sense (until 25 April), is the second exhibition in a three-year partnership between Windsor and London’s Royal Academy of Arts (RA), of which Craig-Martin is a member.

Around 35 recent works are on view (some of which are for sale): in the gallery space are colourful acrylic on aluminium paintings, silkscreen and letterpress prints and an LED lightbox resembling a vision test (letters swapped for common objects); while large single-coloured metal sculptures that look like outlines of objects are scattered throughout the community’s grounds. Depictions of banal objects like tennis shoes, stilettos and sunglasses, as well as juxtapositions of items of furniture and buildings by architect-designers like Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, stop us in our tracks with their crisp black outlines and bold colours—visual candy that also pulls us into a deeper meditation on how we read and recognise images and interact with objects.

The Art Newspaper: I thought it was really interesting that your sculptures here are sculptures of drawings, not sculptures of the object.

Yes. Most sculptures which represent things, you would expect it to be modelled in a three-dimensional way. If you go to any classical sculpture of a figure, it’s three dimensional, you walk around the sculpture, the figure, exactly the same way you would walk around a person. You see it from all angles, you see it in three-dimensional form. Whereas my sculptures—although they are sculptures, they are objects, they are freestanding—but the way in which you read the image is a two-dimensional reading, not a three-dimensional reading, because they’re sculptures of drawings of things, rather than models of things. So when you look at my sculpture, if you look at it from the side, you get a single line, and if you walk around to the front, you get the full image.

Michael Craig-Martin, Umbrella (yellow) (2011), installed at on the grounds of Windsor, Florida Photo: Aric Attas; © Michael Craig-Martin; courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

I know you’re interested in semiotics and conceptual art, but [your work] is also very accessible.

I look back at the art of the past, and much of what I really admired is art that is accessible to different people at different levels of experience and understanding. In Europe, you go to the great churches of the Middle Ages or you go to the museums in Florence, where by far, the majority of the population was illiterate [at the time their Old Masters works were created]. And, if you think about it, the only time they probably ever saw a picture in their daily life was on a coin. Can you imagine how miraculous it was then to go to a church full of imagery. Because really there weren’t images out around, there were no [widely circulated] books—unless you were very rich you had no reason to see images. And yet, the peasants went to church, and the stories were from the Bible which they knew, so the simplest person could understand [the painted and sculpted scenes] as well as the most sophisticated people in society. And I’ve always thought: “That’s a good model.”

I really like the [works] where you have overlaid [linear depictions] of older technology and the new version of that [object].

It’s a set of prints called Then and Now. I’ve been making drawings of ordinary things since 1978, and I’ve built a vast compendium of images of individual drawings of things. I hadn’t realised when I started that I would end up being a kind of recorder of objects over time, because objects that were commonplace in the 1970s are much less so now, and the character of objects has changed very dramatically. In most of the 20th century, form followed function, so an object looks like what it’s supposed to do. If you take an iPhone, it’s a camera, it doesn’t look like a camera; it’s a computer, it doesn’t look like a computer; it’s a diary, it doesn’t look like a diary. It looks almost like nothing, and yet it performs the function of, say, 15 objects. The old telephone, you picked up the receiver and there was a bit you listened to and a bit that you spoke into and they were held at the right distance; on the iPhone, who knows where you’re speaking into and who knows where the sound is coming from? So, when I became more and more conscious of the way things were changing, I thought to make a set of prints in which I took an object from the past—but in my own past, not hundreds of years ago, just decades ago—something like a tape cassette. That’s the funniest one, because if you show some young person a tape cassette, they have no idea what it is and it’s so bizarre for them. If you tell them there’s a bit of tape that actually runs on wheels—

And you have to wind it with a pencil eraser!

You could never explain that—the idea that it’s so physical there’s literally tape moving from this ring to that ring—how weird is that for somebody today? The idea of that physicality? We went from tape cassettes and then we went to CD’s, but CD’s are now old hat, because we have music that comes over the Internet, so I used the symbol of Spotify. Essentially, we’ve removed the necessity of an object at all. And that’s an extraordinary change—from the mechanism of a tape cassette, to no mechanism.

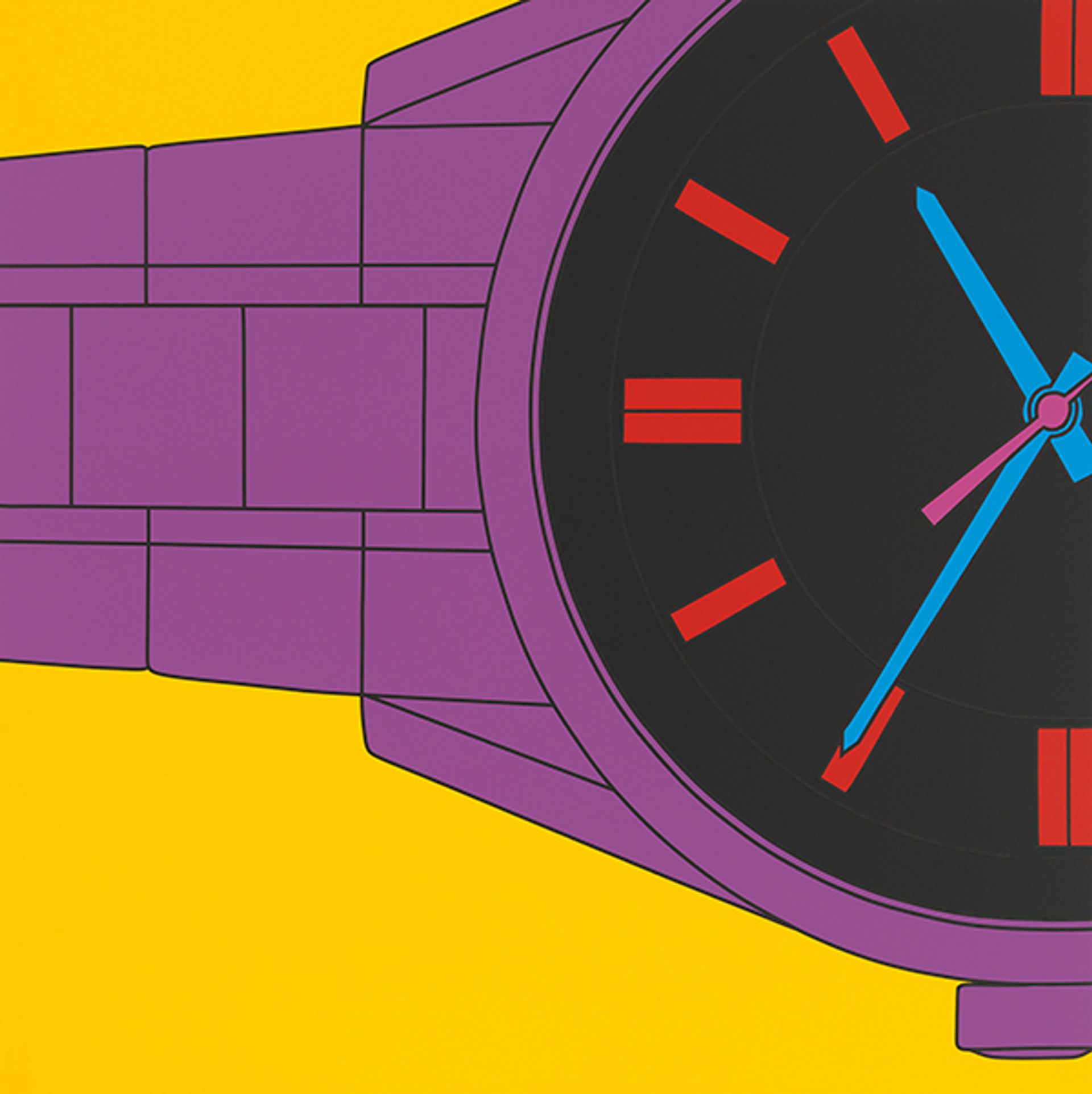

Michael Craig-Martin, Untitled (watch fragment yellow) (2018) Photo: Mike Bruce; © Michael Craig-Martin; courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

What about the square format [of many of the paintings], especially the ones that are cropped?

It’s a little complicated, but I’m trying to emphasise the fact—this is also why there’s no framing, why the paint goes to the edge—[that] I’m using two-dimensional images for you to identify, for you to read. So, if I do a painting of a shoe, you don’t go up to the painting and say “it’s a painting”, you go up and say “it’s a shoe”. Well, it’s not really a shoe, is it? And that’s what interests me, the fact that we are so good at reading images that it overrides other things. I’m trying to emphasise its object-ness. And that’s one of the reasons why [I use] the square [format], and why I want you to see the size of the painting. I don’t want a frame, because that would be another object which would emphasise the image-ness of the image. The image is already too powerful—I’m trying to make you look at the object that I’m making, which is the painting.