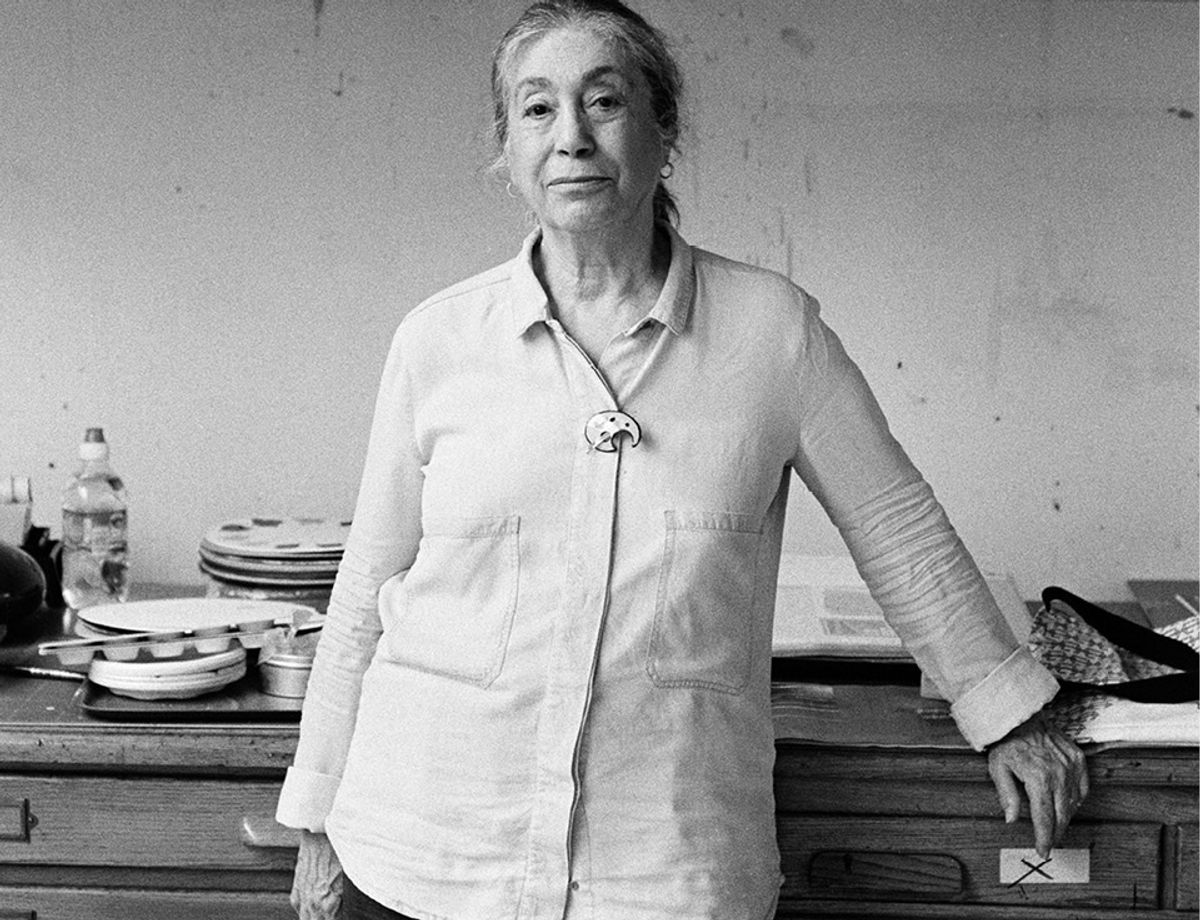

The US-born, London-based artist Susan Hiller died on Monday (28 January), aged 78, following an illness, according to a memorial released by her gallery Lisson today. Hiller, who held a doctorate in anthropology, became disenchanted with the field and its supposed “objectivity”, and decided to become an artist during a lecture on African art. “In art, the viewer can be forced into a situation that creates empathy, which cannot be done in the social sciences,” she said in a lecture last year on the occasion of her most recent major solo show, Susan Hiller: Altered States at Polygon Gallery in Vancouver, as reported by Hyperallergic.

Hiller was born in Tallahassee, Florida in 1940 and grew up in Cleveland, Ohio and south Florida. She graduated from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts in 1961, then studied film and photography at The Cooper Union and archaeology and linguistics at Hunter College, both in New York. In 1965, she earned a PhD in anthropology from Tulane University in New Orleans, and went on to do field work in Mexico, Guatemala and Belize, but decided that she did not want her research to be a part of the “objectification of the contrariness of lived events”, she wrote.

Hiller began her five-decade art career after moving to London in the early 1960s, where she has mainly lived since. Her work across multiple media—installation, film, painting, writing, sculpture and photography—has drawn from cultural artefacts, and she started using audio and visual technology in her work in the early 1980s. The artist called herself a “paraconceptualist”, and her recent Vancouver show, Altered States, looked at the artist’s interest in dream states, paranormal activity and the cultural unconscious. Works in the show included the five-screen video piece Psi Girls (1999), which shows two-minute clips from films with young girls who have telekinetic or pyrokinetic abilities, such as The Craft and Matilda, to a percussive soundtrack.

One of Hiller’s best-known pieces, From the Freud Museum (1991-96), first shown at the Freud Museum in London and now in the Tate’s collection, is a massive vitrine with 50 cardboard archive boxes of various found objects and photographs, from mass-produced items like 45 records and knickknacks to copies of ancient artefacts, along with a video projection. “My collection offers some indigenous symbols and references that position me — and maybe you — as outsiders who don’t understand things that make perfect sense to others,” she said about the work.

Hiller has shown in hundreds of exhibitions since 1972, including the last two iterations of Documenta in Kassel, Germany, four editions of the Sydney Biennale and a major retrospective at Tate Britain in 2011, and had her first solo shows in London in 1974 at the Royal College of Art Gallery and Garage Art Ltd. Her work is due to be shown in multiple group exhibitions this year, including The World Exists to Be Put On A Postcard: Artists’ Postcards from 1960 to Now at the British Museum, opening next month (2 February-4 August). She has also served as a curator and has taught at universities in the US and UK, including the University of Ulster in Belfast, where she was a professor of art from 1986 to 1991, and most recently at the University of Newcastle, where she served as the Baltic Professor of Fine Art from 1999 to 2002.

“Susan’s significance and influence as an artist is immense and will undoubtedly only increase over time, but her presence, her sharp intellect, her wisdom and her friendship will be much missed by so many,” Ann Gallagher, who organised Hiller’s Tate Britain retrospective, said in a statement yesterday.

“Working with Susan was a privilege, an education, and always inspiring,” says Andreas Leventis, the associate director at Lisson Gallery. “She was exacting, irreverent, mercurial, warmly mischievous, caring, and considerate. Expert on a diverse array of subjects, she wore her knowledge lightly and questioned everything. She was an influential teacher to several now well-known artists, and always supported her peers and colleagues by showing up, speaking out, and telling it like it is. Susan will be missed terribly, by many.”