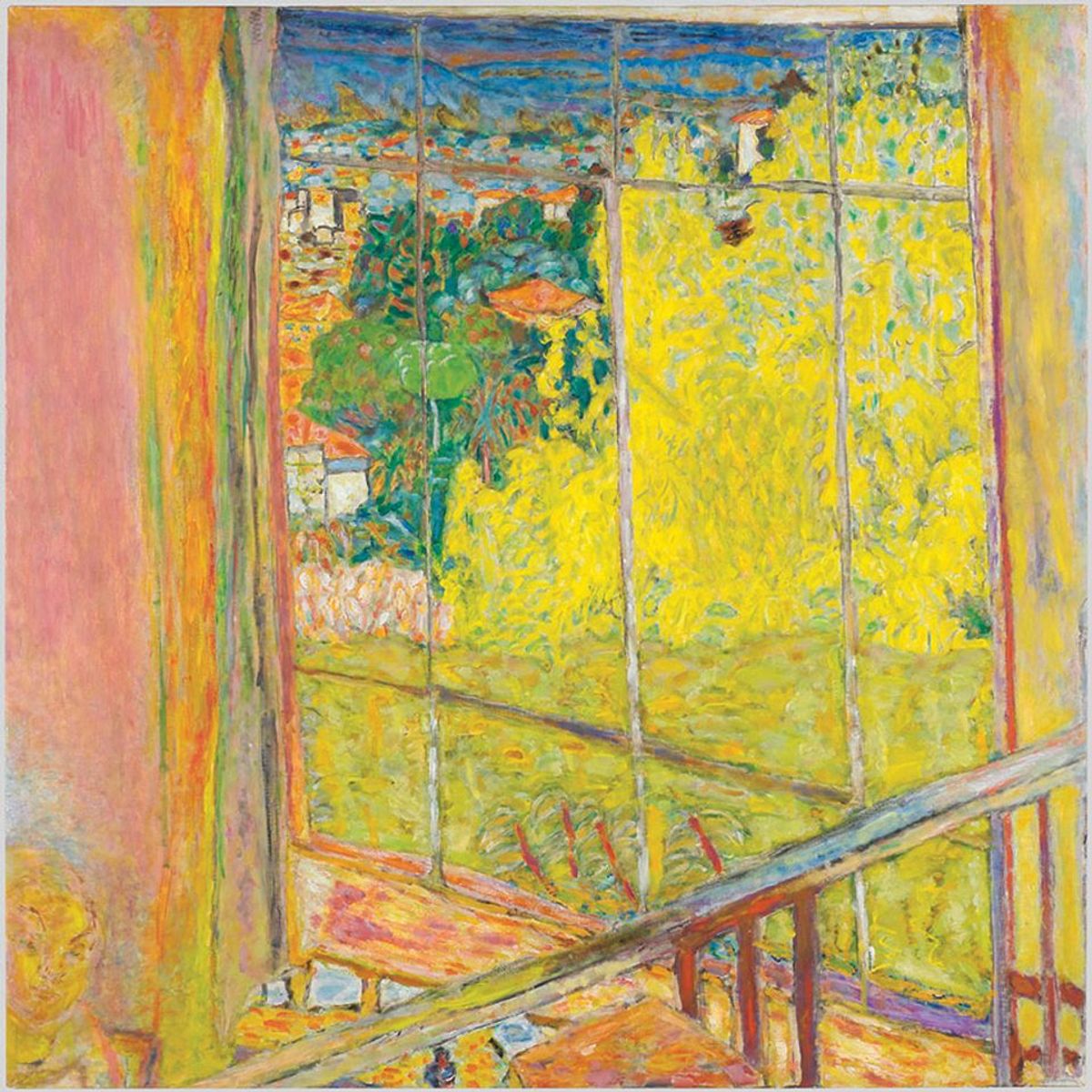

Pierre Bonnard: the Colour of Memory (until 6 May; tickets £18, concessions available) at Tate Modern charts the final four decades of the French artist’s career, skipping his early work at the end of the 19th century when he was associated with the Nabis group. The large exhibition is primarily a show of domestic scenes, snapshots—heavily influenced by photography—of his home life: Bonnard’s long-term partner bathing, dining tables and chairs, bowls of fruit, water jugs, flowers in vases, and gardens beyond viewed through open doors and windows. All the quotidian scenes have been collapsed and flattened into patches of colour. Pablo Picasso was not a fan of Bonnard, damning his work as “decadent” and “a potpourri of indecision”. Perhaps it was the way Bonnard applied patches of colour, patted on with a seemingly near-dry brush unburdened with paint. The colour saturation dial is turned up to 11. But these colours sing when Bonnard is depicting the vibrant and verdant foliage of gardens, such as In The Violet Fence (1923) with its picket fence tearing across the foreground, or flowerings trees, such as in The Studio with Mimosa (1939-46). He would have been a dab hand at painting potpourri.

Despite the title, Bill Viola / Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth opening on Saturday at the Royal Academy of Arts is primarily a Bill Viola show (26 January-31 March; tickets £20, concessions available). There are 14 Michelangelo drawings and his relief sculpture The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John (around 1504-05)—the only such example by the Old Master in a UK museum (and usually on display for free). But the Taddei Tondo, as it is also known, has never looked so good, expertly lit and sitting opposite Viola’s Nantes Triptych (1992), his greatest work. Michelangelo’s drawings are, of course, exquisite and rather than sketches or studies for bigger works, they are “highly finished drawings” according to the organisers. One of the highlights is the playful and bawdy—notice the child urinating into a food bowl—red chalk drawing A Children’s Bacchanal (1533), given by Michelangelo to his lover Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. It would be unfair to compare Viola with Michelangelo, and with 12 major installations by Viola this show is very much one for fans of the US artist.

Round the backend of the Royal Academy at Pace Gallery is an exhibition of the little-known Abstract Expressionist Richard Pousette-Dart. Some of the works might perhaps appear a bit naff on first glance but spend only a little time in their presence and their delights reveal themselves. Pousette-Dart (1916-92) was a one of the youngest founding members of the New York School, an early Abstract Expressionist and reportedly the first of the group to create large-scale paintings. The works in Richard Pousette-Dart: Works 1940-1992 (until 20 February; free) span six decades and include a selection of works on paper from the 1940s that have not been exhibited before, according to the gallery. Get your eyes up close to the seemingly simple abstract paintings and they are awash with varied and precisely applied dabbles of colour. The apparent grey of the large canvas Presence Number 3, Black (1969) is made up of blacks, browns, greens and blues with yellow and pink specs dashed on. Magnetic Space (1961), measuring almost three metres in width, is made up of daubs of lavender, baby pink, clay brown, sky blue, gunmetal grey and looks like Pousette-Dart took to rearranging the dots in Georges Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884).