A new touring show and scholarly catalogue combat a common perception of the Sahara Desert as a wasteland or blank geography. In the Medieval era, the world’s largest desert was actually a robust trade route connected to Asia’s Silk Roads. Organised by the Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University near Chicago, Illinois, Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time is the first show of its kind to reveal how sumptuous artwork and decoration in gold, glass, ceramic and copper flowed through the region by horse and camel, assisted by the spread of Islam.

The show’s curator, Kathleen Bickford Berzock, says it has been eight years in the making. “The depths of this history are so astounding and so little acknowledged in the way African art is presented in museums,” she says, referring to an overemphasis on colonialism and the slave trade.

A bioconical bead from Egypt or Syria (10th-11th century) © The Aga Khan Museum

Bickford Berzock's exhibition paints a broader picture of medieval Africa as a major example of globalism and multiculturalism from the eighth to the 16th centuries. “Finding the tangible remains of this world history is thrilling,” she says. Her show brings together around 250 artefacts from excavation sites in Mali, Morocco and Nigeria, the countries that today represent the western, northern and southern reaches of the historic Saharan trade routes.

True to the show title, there are plenty of gold objects that uncover why West African gold was known as the purest, including jewellery from a Nigerian tomb, and gold from a shipwreck that was being smuggled into England from Morocco. An exquisite biconical bead (10th-11th century) from Egypt or Syria was made from gold droplets fused together. “We have some remarkable pieces of gold in the exhibition,” says the curator, who adds it is rare for US institutions to work with African lenders.

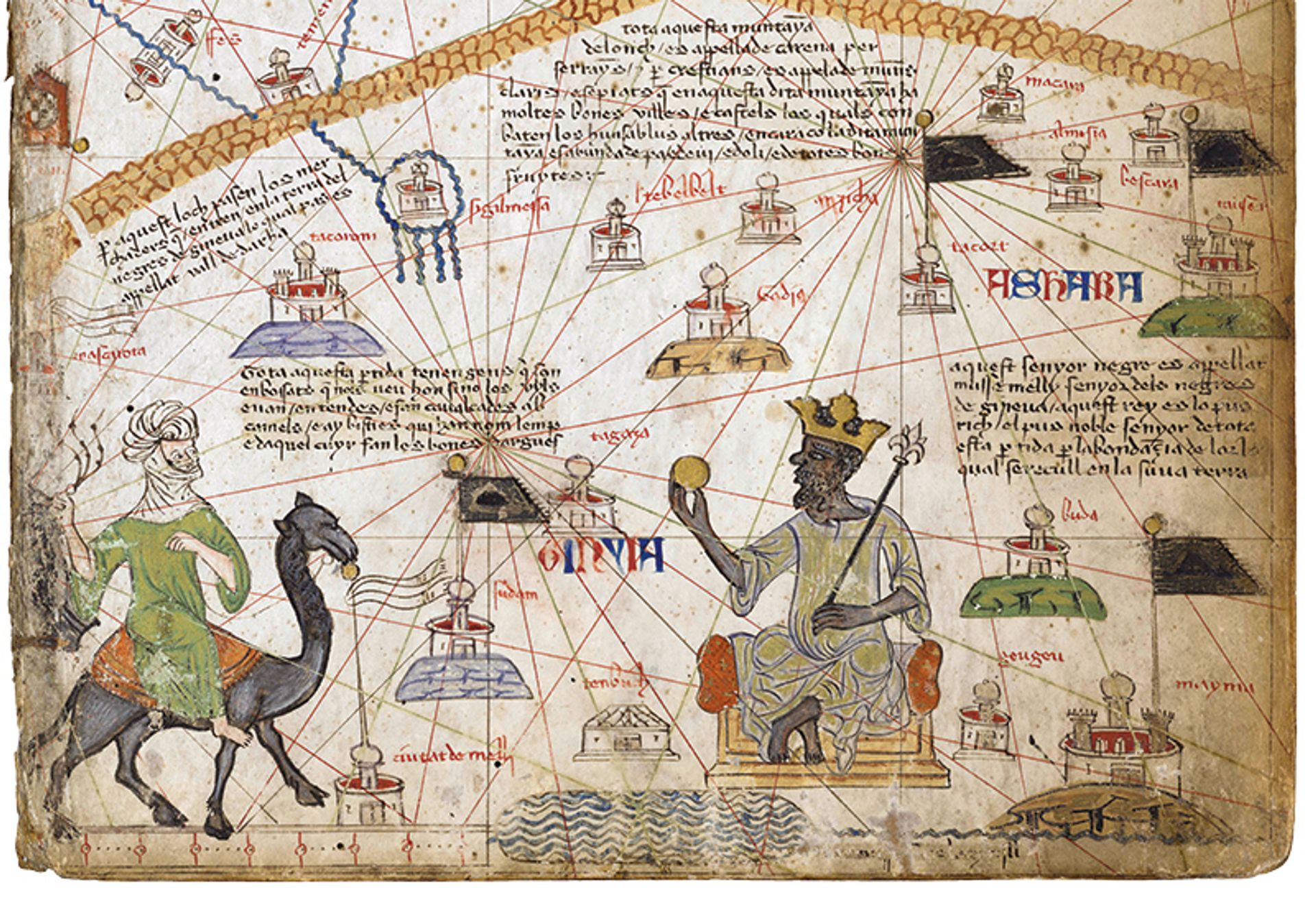

A 1375 Catalan Atlas linking West Africa to the wider world trade system © Bibliothèque Nationale de France

A key artefact in the exhibition is a potsherd (a broken piece of ceramic) of Chinese porcelain with subtle blue-green glazing excavated in Mali. Dated between the 10th and the 12th century, the bowl fragment represents the far reaches of cultural trade in this period. “It’s mind-boggling to imagine that kind of connectivity in the medieval era, which is often misunderstood as an era of isolationism,” Bickford Berzock says. “But this fragment is tangible proof that connectivity was real.”

Bickford Berzock says that the relevance of medieval Saharan trade for present-day visitors to the exhibition lies in the fact that these are the “same routes used today by migrants avoiding conflict. We see so many issues of boundary building these days—who belongs where and why—but in medieval Africa, border crossing was constant.”

Gold jewellery from Nigeria (13th–15th century) © National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Abuja, Nigeria; Photo: René Müller

Bickford Berzock encourages visitors to the show to use their “archaeological imagination” since most evidence of global trade from this era exists only in fragments. Nearly a third of the show’s medieval checklist has been supplemented with comparable examples from the 17th to the 21st centuries to help fill in the gaps. “It’s an imperfect methodology,” she says, “but the alternative is not to have an exhibit at all.”

The main sponsors are the National Endowment for the Humanities and Northwestern University’s Buffett Institute for Global Studies. The exhibition will travel to the Aga Khan Museum in September 2019, and the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institute, in April 2020. A catalogue is co-published by the Block Museum of Art and Princeton University Press.

• Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture and Exchange across Medieval Saharan Africa, Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, Chicago, 26 January-21 July