An anniversary most often offers the opportunity to celebrate the life and work of an important figure; less often does it prove necessary to consider who it is that we are celebrating. The latter is perhaps the case with John Ruskin, the bicentenary of whose birth in February will occasion a great many books and exhibitions.

Such was the extent of Ruskin’s fame in his mid-19th-century prime that it accommodated his many activities and achievements, whether in art criticism, architectural history, geology, botany or political economy. Indeed, it is difficult to think of a comparable figure read so widely, and whose influence was both so great and so broad. The diminishing of his fame has obviously led to a lack of familiarity with his work; if he now exists in the popular consciousness at all it is more likely to be in his recent film and TV portrayals as a supporting role to the artists whom he championed, J.M.W. Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites foremost among them.

John Ruskin's Study of a Peacock's Breast Feather (1873, detail) © Collection of the Guild of St George / Museums Sheffield

The coming events should encourage us to reconsider Ruskin in his infuriating, brilliant complexity and the first, John Ruskin: the Power of Seeing at Two Temple Place in London, is a good place to start. Organised by Louise Pullen from Museums Sheffield, where the show will travel to in May, the survey brings together a vast array of works and other objects in order to explore how Ruskin’s attitude to aesthetic beauty affected the development of his radical views on culture and society; these range from paintings by Ruskin, Turner and their contemporaries to furniture made especially for his St George’s Museum, an institution he opened for the workers of Sheffield in 1875.

Ruskin’s views remain radically useful, still, not least to Grizedale Arts, the influential arts organisation situated barely a geological specimen’s- throw from Ruskin’s former home, Brantwood, in the Lake District. Since 2000, Grizedale has commissioned many projects that have at their heart a desire that art make a valuable contribution to society—in 2012 it commissioned the artist Liam Gillick to renovate the Coniston Institute, which had previously been rebuilt by Ruskin in 1878—and so its presence within the exhibition should emphasise how his thoughts on the political economy might still be employed.

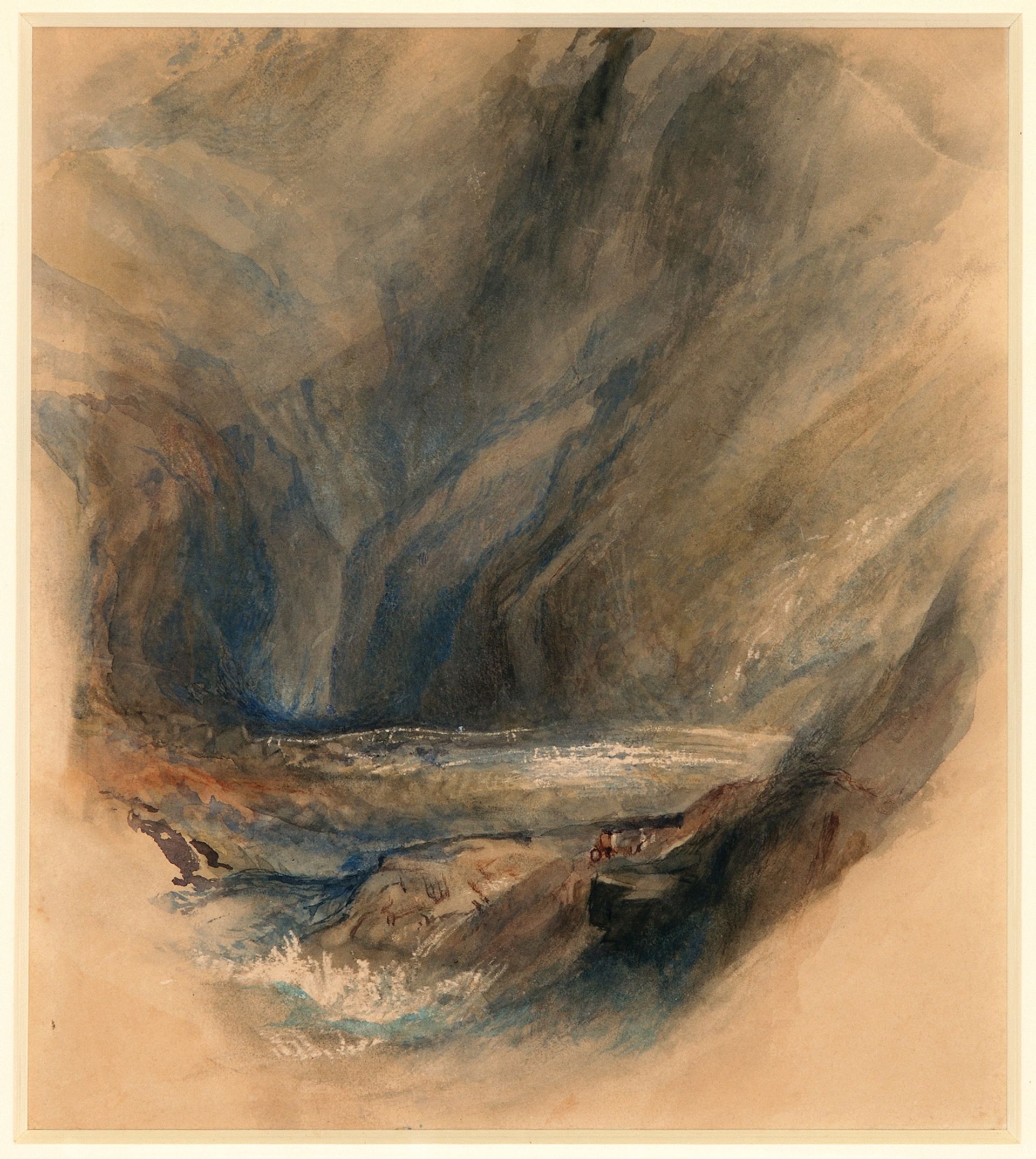

John Ruskin after J.M.W. Turner, Detail from the Pass to St Gotthard (1855) © Collection of the Guild of St George / Museums Sheffield

The director of Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery, Alistair Hudson, oversaw the restoration project at the Coniston Institute during his time at Grizedale, and so the exhibition opening at the Whitworth in March—taking place among objects from the museum’s own Ruskin-inspired collection of art and design—will be similarly thought-provoking. Manchester was the site of one of Ruskin’s most famous lectures, an impassioned railing against the city that he considered the grimy manifestation of all that was wrong with industrialisation. The lecture led to his book, Unto This Last (1860), a volume that proved a major influence upon politics in the UK and abroad (Gandhi translated it into Gujarati in 1908).

In a period of renewed interest in the efficacy of socially engaged artistic practices and—more importantly—despair at our own social, economic, and ecological circumstances, Ruskin’s voice is one that should be both celebrated and challenged, but certainly engaged with. One hopes that these events over the coming year will necessitate just that.

• John Ruskin: the Power of Seeing, Two Temple Place, London, until 22 April; Millennium Gallery, Sheffield, 29 May-15 September

• Joy for All: How to Use Art to Change the World and its Price in the Market, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 29 March-9 June

• For more Ruskin-related exhibitions and events, see Ruskin To-day