The Getty Conservation Institute announced today (22 January) that it had completed nearly a decade of work on the Tomb of King Tutankhamen with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, leaving it in a condition in which it will be able to stand up to future visitors.

Central to the conservation effort was a study of the 3,300-year-old Egyptian tomb’s famed wall paintings, which are marred by brown spots that conservators feared might be growing. But as previously reported, scientists blew up some photographs that were taken in the 1920s after the burial site was discovered by the British archaeologist Howard Carter and determined that the darkened areas had not budged.

DNA tests and chemical analysis indicated that the spots were microbiological in origin but dead and no longer a threat, the institute adds. The spots have penetrated the paint layer and therefore could not be removed because that would have damaged the paintings, which depict Tutankhamen’s life and death.

Most of the tomb’s treasures were removed in the decade following its discovery. Today it houses only a few objects including the mummy of Tutankhamen, a sarcophagus and a gilded wooden coffin.

When the joint conservation initiative began in 2009, the Egyptian authorities were concerned not only about brown spots, but also scratches and abrasions on the wall paintings in areas where visitors have access and film crews have passed through with cables, lights and other equipment. Dust tracked in on visitors’ shoes and clothing had settled on the walls, dulling the brilliance of the wall paintings. And visitors were causing humidity to spike, another source of stress for the paintings.

The project involved the most intensive study of the tomb’s condition since Carter discovered it in 1922. The team included an Egyptologist to conduct background research, environmental engineers to test the tomb’s microclimatic conditions, microbiologists to study the brown spots, architects and designers to upgrade the infrastructure, scientists to study the composition of the wall paintings and conservators to treat the walls.

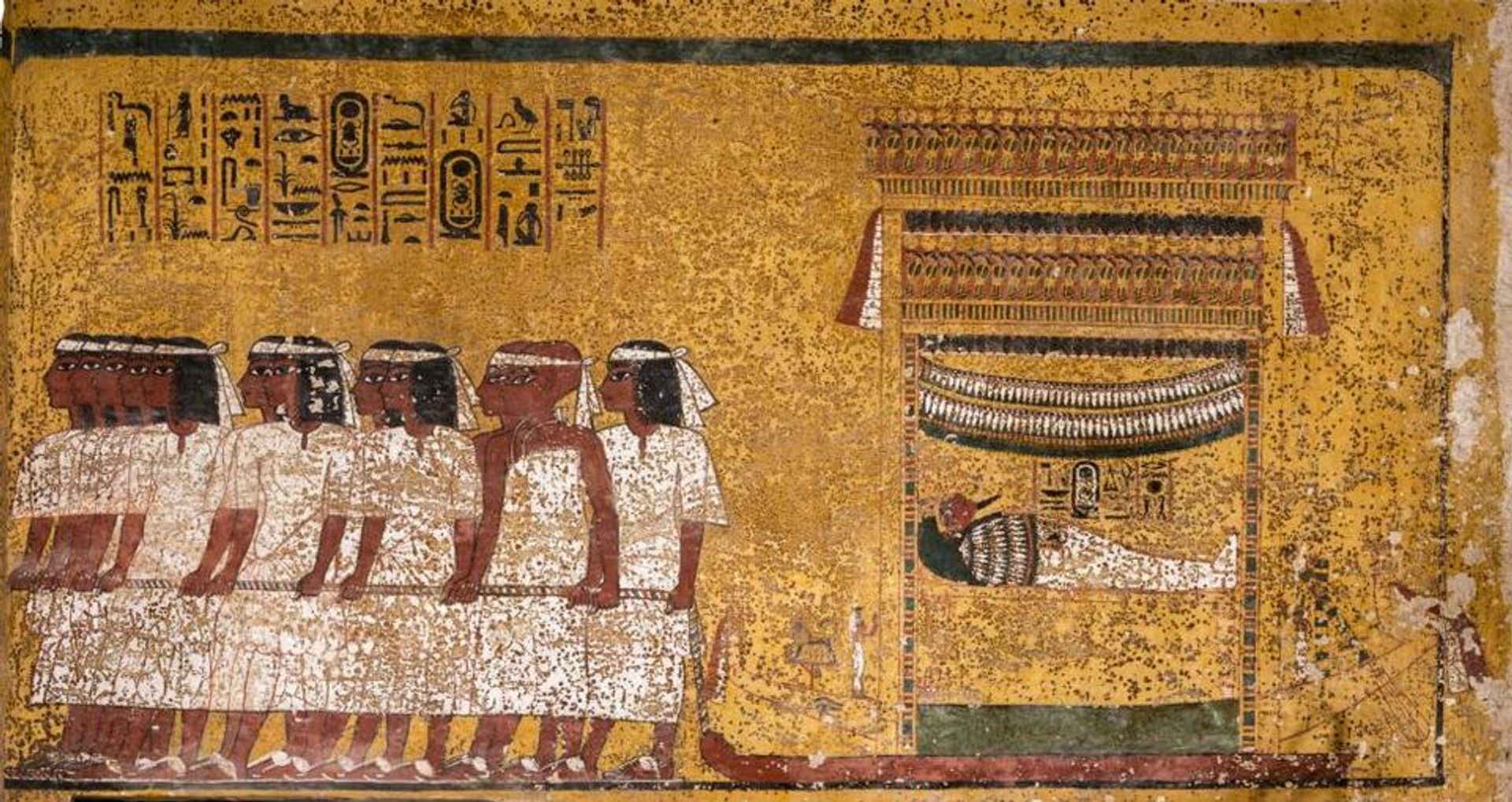

Painting on east wall of the burial chamber in the Tomb of King Tutankhamen © Carleton Immersive Media Studio/Carleton University; © J. Paul Getty Trust

After an intense period of study, conservators treated areas of minor flaking on the paintings with adhesives to attach the particles, says Lori Wong, a project specialist with the Getty Conservation Institute who specialises in wall paintings. “These paintings are over 3,000 years old, and given their age, the condition is quite good,” she says, particularly when compared with those in other tombs in the Luxor region. “We did not do any repainting or restoration. Everything that’s visible in the tomb is original.”

But the biggest impact of the conservation effort was installing infrastructure like a ventilation and filtration system to limit humidity and dust in 2015, she says. “Visitors can release a lot of moisture,” she says. “These environmental conditions were far more serious than the flaking.”

After the ventilation and filtration systems were installed, conservators gently cleaned the wall paintings to eliminate the dust, some of which was embedded in the surface. Egyptian conservators had used biocide treatments with an adhesive over the years to kill any microorganisms on the paintings, resulting in shiny areas; the Getty team reduced the adhesive so the shininess disappeared.

The old viewing platform at the entrance to the burial chamber was replaced with a narrower one so that visitors could no longer touch the wall paintings. But the replacement extends further into the chamber, allowing an improved vantage point. New signs on the tomb’s modern history remind visitors of the impact that their presence has on their surroundings. And after a period of experimentation, the conservators recommended a limit of 20 visitors at a time who can stay for no more than 10 minutes, according to Wong.

The tomb remained open for much of the project, enabling visitors to pose questions as the conservators worked. “You’re basically on view for the entire day,” Wong says. “We often engaged with people. It was interesting to see what they were taking away from their visit.”

During the period of detailed study, the team also gained some insights into how the wall paintings were made, encountering some surprises, Wong says. Even though the burial room is quite small, a slightly different technique was used for painting each of its four walls, possibly suggesting that different artisans were at work.

On one wall, a preparatory ground layer of paint was omitted. A snap technique, dipping a string into paint and then pulling it taut and applying it into the wall to make a straight line, was noted on three of the four walls; on the remaining wall, lines are incised into the plaster. “For us this was an interesting discovery because one would assume that when you’re painting just one room, that all the walls would have a similar technique used,” Wong says. “The fact that we were seeing these differences was quite striking.”

Tutankhamen is thought to have died when he was was 19. Egyptologists have long theorised that he was buried in a tomb that was not originally intended for him, she says. “The inconsistencies that we're seeing in technique could mean that they were hurrying to prepare an existing tomb” for his burial, she adds.

The anomalies suggest that further study is needed of Egyptian painting techniques at other burial sites, Wong says. “A lot of projects are more focused on the iconography of the paintings rather than how they were made,” she says. “There’s probably a lot we don’t know about Egyptian painting technology."