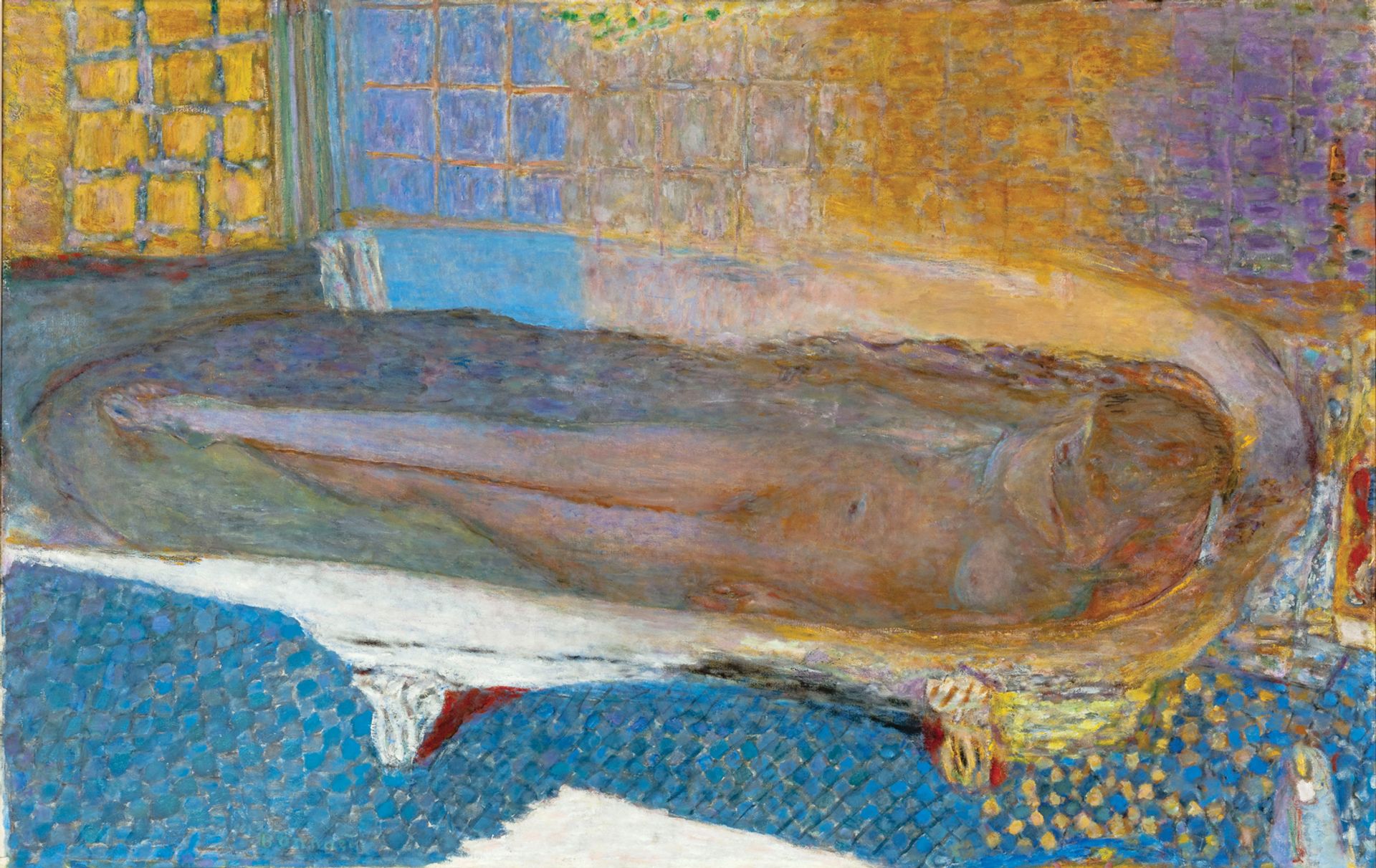

Time takes on a special quality in the paintings of Pierre Bonnard. For the novelist Julian Barnes, the French artist’s languid domestic scenes all seem to “take place a few hours either side of lunchtime”. Bonnard’s companion for almost half a century, Marthe de Méligny, appears ageless in the artist’s continual depictions of her bathing or getting dressed. Preferring to paint from memory over direct observation, Bonnard completed his last Nude in the Bath several years after Marthe’s death.

One of the aims of a new survey of Bonnard’s work, opening at Tate Modern in London before travelling to Copenhagen and Vienna, will be to “pin him down in time”, says its lead curator at the Tate, Matthew Gale. Twenty years since the last major UK exhibition, at the then Tate Gallery, Gale hopes to “rethink Bonnard in a different way” for a new generation.

“Bonnard's works are so dense that you can return to them again and again and see new things”

The broadly chronological show takes its starting point from 1912, a “significant moment” in the painter’s career, when the glowing colours of his mature style began to emerge. Having made his name among the Nabis circle of Post-Impressionists in the 1890s and found regular dealers in the Bernheim-Jeune brothers, Bonnard “could have carried on that trajectory, being a successful artist from the previous century”, Gale says.

Instead he followed a singular path, making sensual, high-key paintings separate from Cubism and Surrealism. Bonnard’s Modernist credentials were duly savaged after his death in 1947. Picasso called him “just another neo-Impressionist, a decadent; the end of an old idea”, while the critic Clement Greenberg said his art “smells permanently of the fashions of 1900-14”.

Pierre Bonnard's Nude in the Bath Huile sur toile (1936-38) © Musée d'Art Moderne; Roger-Viollet

At Tate Modern, “we’re trying to look at his work in the context of the 20th century,” Gale says. Bonnard was “not oblivious to the events going on in the world”, including the cataclysms of two world wars. The show will include a focused display around A Village in Ruins near Ham (1917), his “completely unexpected” response to the Battle of the Somme, made during an artists’ mission to the Western Front. Bonnard’s late still-lifes and landscapes of Le Cannet, the village above Cannes where he and Marthe moved permanently in 1939, were “insular through circumstance”, Gale argues.

While the artist’s interviews, correspondence and even diaries reveal little about his own motivations, Gale says, critics as early as the 1920s made the easy equation between Bonnard and “bonheur”—the French word for happiness. “The thinking behind this exhibition was more about the paradoxical relationship between colour and the atmosphere of the paintings,” Gale says. “Colour is so seductive and joyous, but the undertone is trying to capture a fleeting moment, which is almost melancholic—a sense of trying to seize something passing in front of your eyes.”

A Ruined Village Near Ham (1917) was Pierre Bonnard's “completely unexpected” response to the Battle of the Somme © Domaine public/CNAP; photo: Yves Chenot

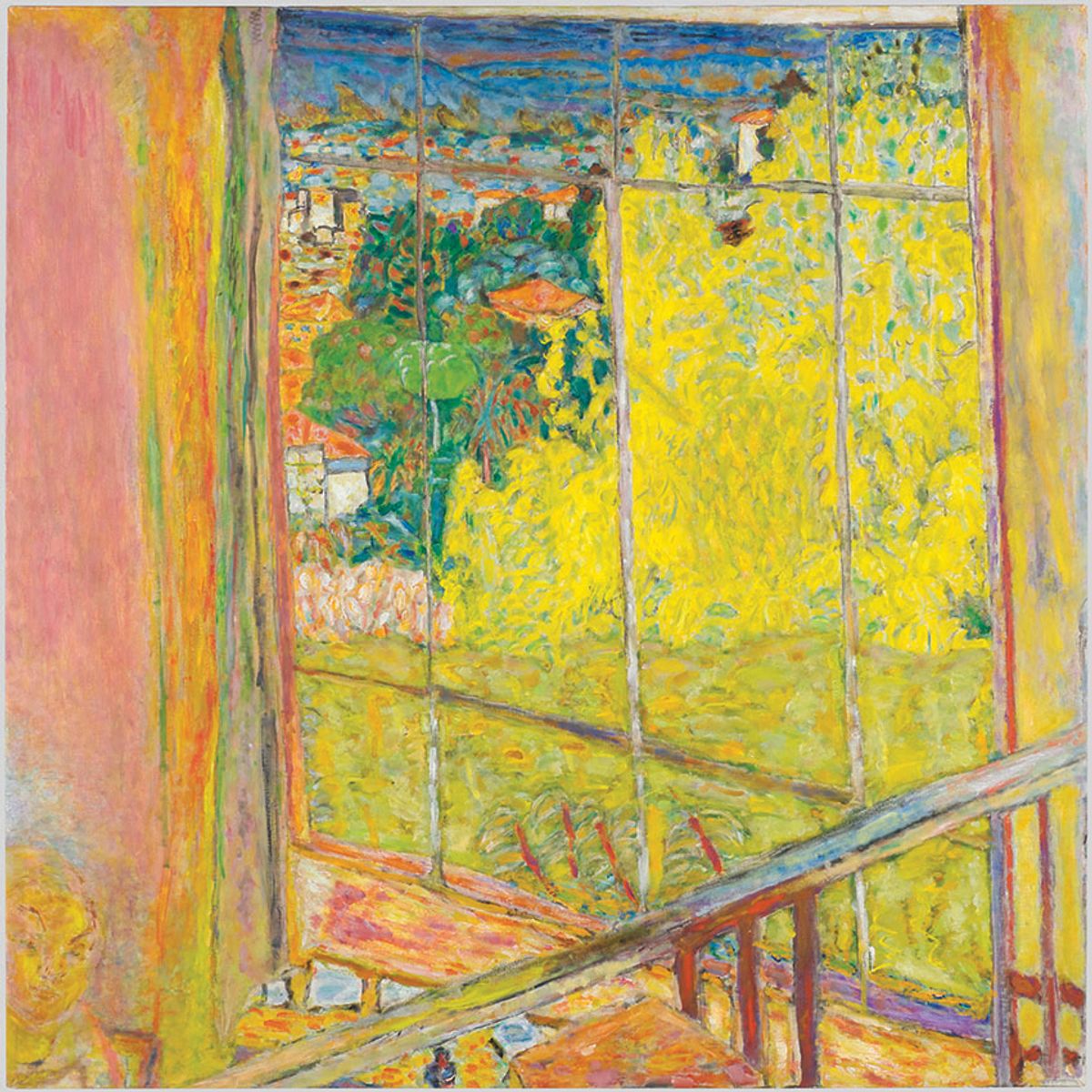

The Tate will seek to prolong visitors’ experience of Bonnard’s paintings through “slow-looking” guided tours, including one with a psychologist, encouraging a dialogue around a few works. The Studio with Mimosa (1939-46), for example, “has an immediate impact and repays careful looking in seeing the details”, Gale says, adding that Bonnard’s works “are so dense that you can return to them again and again and see new things”.

The exhibition is sponsored by the Chinese property developer CC Land.

• Pierre Bonnard: the Colour of Memory, Tate Modern, London, 23 January-6 May; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, 7 June-22 September; Kunstforum Wien, Vienna, 10 October-12 January 2020