The opening of Tate Modern in May 2000 was a strange moment to fall under the spell of the work of the video artist Bill Viola, but I remember it distinctly. Around me a huge party unspooled, with everyone celebrating the arrival of this vast new temple to art. And upstairs, in a darkened room, I sat still for nearly 30 minutes, utterly transfixed by the Nantes Triptych, which the gallery had bought eight years previously. Originally imagined to hang in a 17th-century chapel in France, the work is made up of three screens. On the left, a woman gives birth; on the right, a woman is dying. In between the two states, a body floats in water. The beginning of life, the journey of being, and life’s end.

It was a perfect introduction to Viola’s work—and curiously, not so bad a way to discover it. Throughout his career, Viola’s interest has always lain with the numinous, the sense that there is a spiritual other which rises from and yet is part of the everyday. The intensity and directness of his appeal to the emotions has made him one of the few contemporary artists to be genuinely popular with a wide public.

In his telling, the filming of one section of the Nantes Triptych—the recording of the death of his mother in 1991, which he initially made as a private act, was a turning point in his life and art. In an interview in 2013, he explained that being in the room with her as she died was “profoundly beautiful, profoundly sad, and mysterious beyond belief”. He saw a change in her as the breath left her body and made the triptych as a means of understanding what he had seen. It was the moment that two sides of his life—the films he made of his family, the films he made for galleries—suddenly came together as “two inseparable halves of one creative enterprise”, he said.

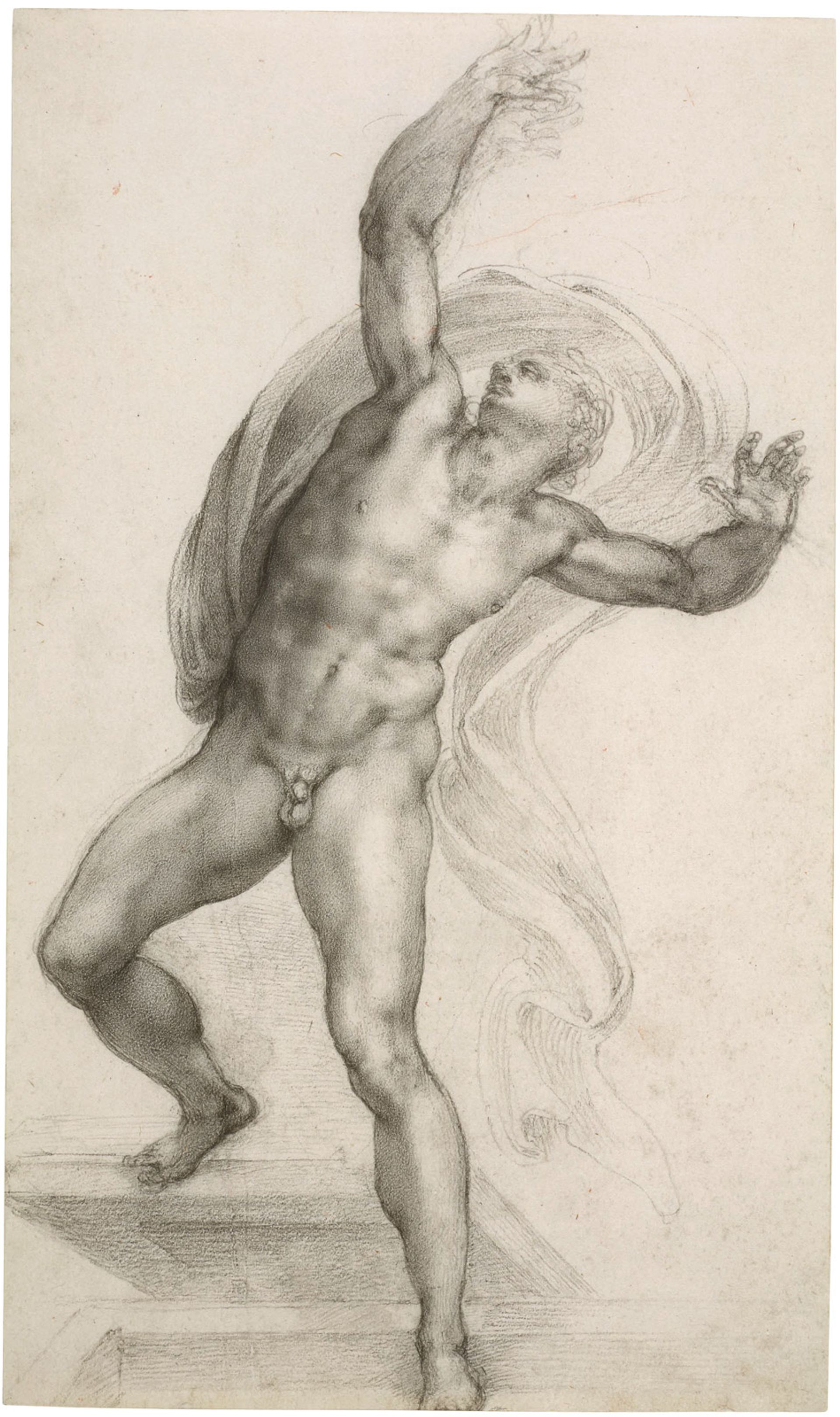

The piece is on display from this month in a Royal Academy exhibition that puts 12 of Viola’s works alongside 14 drawings by Michelangelo. The link between the two artists is that both ask questions about the nature of the soul, while depicting the human body. “When we think of Michelangelo now, we think of him as the painter of the Sistine Chapel and the sculptor of huge figures,” says Martin Clayton, the co-curator of the exhibition. “The emotional and spiritual intent of his work has largely left our understanding, yet for him that was the most important thing.” The show does not seek to compare the two artists—or to suggest Viola is a modern Michelangelo. “It is a significant juxtaposition of two artists who may be working 500 years apart but who are exploring similar, perennial issues about the mysteries of human existence,” Clayton says.

Michelangelo’s The Risen Christ (around 1532) Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2018

The idea sprang from a meeting in 2006 when Clayton, as the head of prints and drawings at the Royal Collection Trust, invited the Viola family—the artist, his wife and collaborator Kira Perov, and their two sons—to see a selection of Renaissance drawings at Windsor Castle. Viola, who had long studied Renaissance art, and been inspired by the Old Masters, was keen to see the drawings of Leonardo. But Clayton also brought out some by Michelangelo. “It is still a highlight of my life,” Perov remembers. “To sit in front of these things, without glass between you and the drawing, is unbelievably moving. You just melt in front of them.”

A little later, Viola began to discuss ideas for a show. “You sense with both artists the notion of rebirth,” says Perov. “There is always resurrection, transformation, transfiguration. They are both asking: ‘What is this life? How am I going to pass through it? And how will I end it?’”.

A deeper understanding

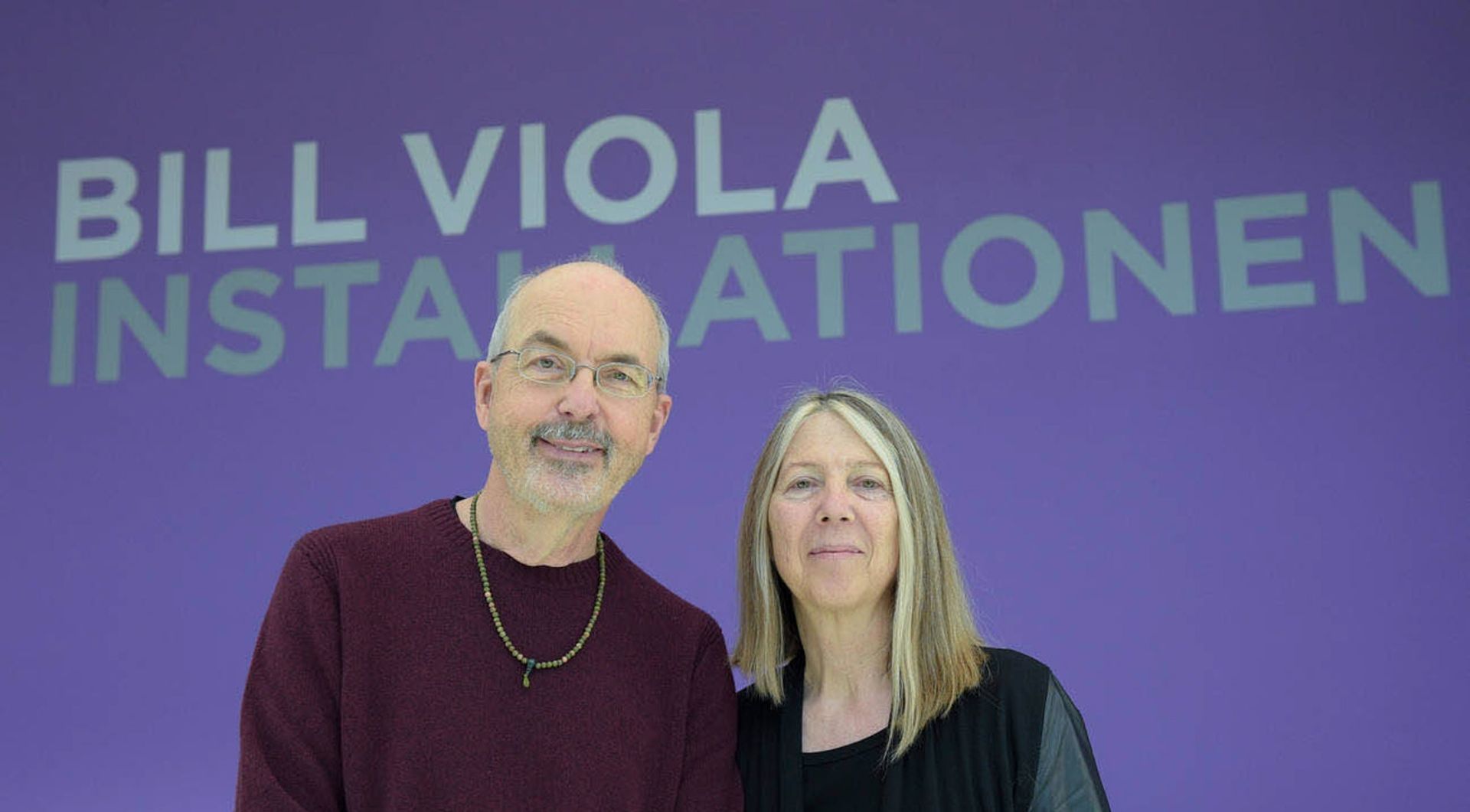

It falls to Perov to talk about the exhibition she has co-curated because Viola, who has suffered from ill health for the past couple of years, is unable to travel. Her knowledge of his work is, in any case, intimate and unrivalled. The couple met in 1977 when Perov was the director of cultural activities at La Trobe University in Melbourne and invited Viola over from the US to show in an exhibition of video art. It helped that his father worked for Pan Am, so the flight was free, but even then, Viola was blazing a trail, experimenting with a form that was in its infancy when he first began to make work as a student in the early 1970s. Their romantic involvement began immediately. By the time the international phone calls had racked up huge bills, Perov decided to leave for the US to be by his side.

Viola with his wife and longstanding collaborator, Kira Perov Photo: Axel Heimken/dpa/Alamy Live News

“I was an adventurer from the beginning,” Perov says. She began to work as a photographer but also became part of Viola’s life and work. By 1979, they were filming mirages in the Sahara together; in 1980, they went to Japan for 18 months, studying Buddhism while Viola worked as an artist in residence at the Sony laboratory. They were a team; from the earliest days, Perov took responsibility for photographing his work; later she organised exhibitions and managed his studio. “I was assisting him. He had ideas and he would make shot lists of things he wanted to get and I would help organise them.” As the years have passed, their collaboration has deepened and broadened. “In the beginning, it was just me, with Kira doing what I said,” Viola said in an interview in 2014. “But over time, she has become like a midwife to the work, checking how the baby is doing, as well as handling all the practicalities of delivery.”

Perov uses the same analogy, but in a slightly different way. “I help the pieces get born,” she says. “Traditionally Bill would lock himself away in his study and he would read and write and work on new ideas and then at some point I will come in and say: ‘Ok, time’s up, enough sitting, writing and reading, what are we going to do?’. Then we would go over the ideas together and some would jump out at me. He would come up with hundreds of ideas for pieces, and we would choose the ones that spoke to the situation or what was next in his development. I was a sounding board.”

Contemplative groupings

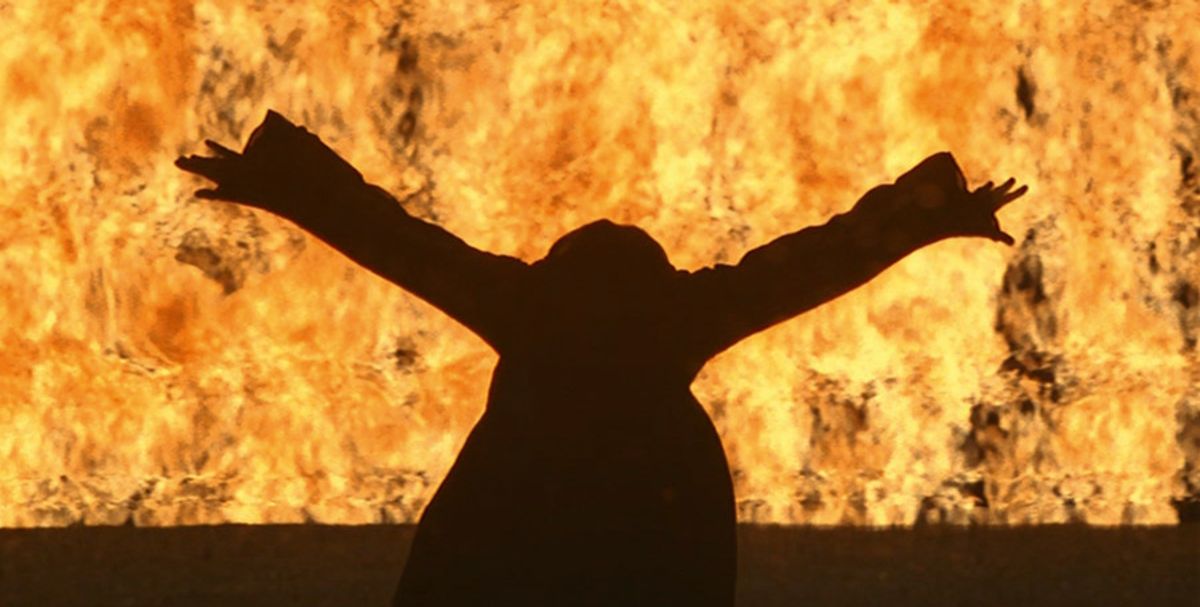

Viola’s subject matter has remained consistent over his career, but the appearance of his work has altered radically, moving from jerky black-and-white to slow-motion, high-definition images that use actors and the elements (principally water and fire) to create emotional, thought-provoking effects. This was partly his response to an ever-evolving technology that enabled him to develop his work and let his imagination fly. Perov points out, for example, that it was the development of flatscreen technology that enabled him to move into close-up portraits such as those in The Passions series (2000-03), quintets of figures in the grip of powerful emotion, reacting in almost imperceptible motion, in a mirror of the contemplative groupings of Old Master paintings, or The Dreamers (2013), where figures are submerged, apparently peacefully sleeping, in water.

But there was another change going on. “The early work had been all about me,” Viola said in 2014. “I was probing myself in a medium that is exactly made for that. It takes you, flips you round and shows you yourself. But at a certain point, I realised that I was constantly hitting some sort of wall and I finally figured out that I should be on the other side of the camera… Doing it this way, it became not about one person but about everybody.”

Eternal questions

The works he has come to make, such as Five Angels for the Millennium from 2001, where a man repeatedly plunges into a deep pool, or Tristan’s Ascension (2005) in which an inert body is awakened and drawn upwards by a backwards-flowing waterfall, are huge productions, requiring vast numbers of people to create, and taking weeks to film, in long, concentrated takes. In this context, Perov sees her role as that of “a guardian angel”. She says: “I would always be there and sometimes I could see more clearly, because I could look from the outside. My main concern would be not to go off the track. To make sure Bill’s idea was going to be created the way it should be.”

Most of the people working on the film “came from Hollywood”, Perov says, “and they were doing a new thing every week and it was all go, go, go. Whereas we had a completely different way of doing things and approaching ideas. We are painting with video, basically. We allow things to evolve and then the piece creates itself. It is just an extraordinary experience. You just keep working, working, working and all of a sudden everyone gets it. Everyone goes quiet and then the piece happens.”

The spiritual dimension of Viola’s work is there in the making. The intensity and integrity he brings to the pieces communicate themselves to the viewer. Not everyone responds to their overt sincerity. But their power to suggest otherness, to reach for spiritual values without offering answers, makes them unusually compelling. Like the paintings of Mark Rothko, they encourage people to look and to think. An audience survey taken after a Viola retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris revealed that people stayed in the exhibition for an exceptionally long average of two and a half hours.

“It is all questions, there are no answers,” Perov explains. “A single line from the [13th-century Persian] poet Rumi, or a particular Renaissance painting, can inspire an image or an entire piece. Bill learns from his experiences or his readings. These questions don’t belong to Bill or me—they belong to everybody. That is the reason these works are universal. Anyone can see them and recognise something, and they realise they can reflect on something they don’t reflect on in their normal life.”

This takes her back to Michelangelo’s drawings of the Crucifixion. “When we first saw them, we were in tears. Here is an artist towards the end of his life, wondering about death. There are holes in the paper, he is pressing so hard, trying through his body, through his creativity to figure it out. It was so moving. It is such an honour for Bill to share a space with him. It is not to make comparisons, but to show the continuation of the thread of creativity and spirituality that is contained in both artists.”

• Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 26 January-31 March