Could be Dana Schutz’s show of athletically surreal, new paintings had something to do with it. It was after leaving her resonant 10 January opening at Petzel that I stepped onto Tenth Avenue in Manhattan and found myself in a landscape straight out of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville. “When did this happen?” asked the artist Fred Tomaselli, startled. Here was dystopian science fiction become real—apparently, Tomaselli noted, over the Christmas break.

The High Line is no longer visible from the street. It’s been obliterated by overscaled, indescribably awful architecture pretending to be futuristic. Before the holidays, much of it was hidden behind scaffolding. Now the transformation of industrial Chelsea into a glassy corporate version of Soviet block housing is inescapable.

Some galleries, like Pace, David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth, have thrown in their lot with developers to build new multistorey galleries that may still be swallowed up by their towering surroundings. Maybe they’ll be magnificent, but an environment this alienating doesn’t feel good for art. It’s still a personal pursuit, no matter what alternatives to lived experience the Internet imposes.

Yet on opening night of the new season, at least a dozen galleries gamely offered sanctuary. Among the most notable was at Zwirner. God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin has a story to tell, and it isn’t about real estate.

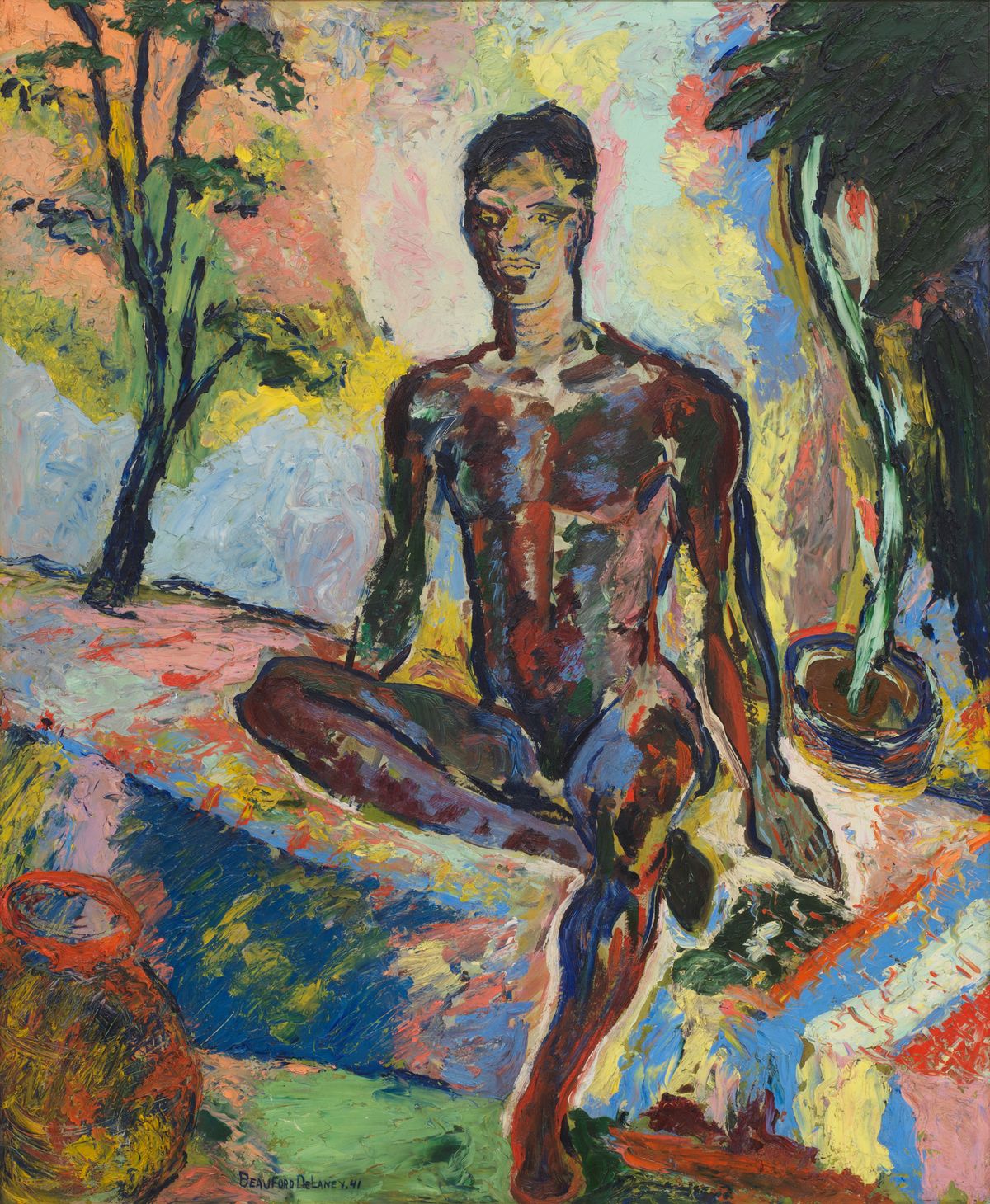

“This show is amazing,” I heard, from several people, the moment I went inside. That doesn’t say anything. Thematic group shows can feel forced. This one isn’t. The New Yorker writer Hilton Als waved the curatorial wand here; clearly, he had access to material known mainly to scholars. They include a standout portrait of Baldwin by his friend Beauford Delaney, as well as letters, books and sketches by the subject at hand and archival photographs by unknowns.

Baldwin is a towering literary figure in our culture, but he was also a preacher and a political agitator who found a more enlightened home in Paris than at home in Harlem. This, we know. It’s his legacy as a gay man and a sexualized, social being that emerges from the biographical narrative unwinding here.

To his credit, Als lets the art do the talking, even though he was the one to shape it. The show has two parts: Baldwin as an urban flaneur, and as a powerful voice for both civil rights and the contradictions within black masculinity.

Much of what’s on view we’ve seen before. If the context doesn’t change its meaning, it does deepen our understanding of Baldwin and a circle of friends that included Richard Wright, Marlon Brando, Richard Avedon, Jean Genet and Langston Hughes, all of whom are pictured in a suite of 14 watercolour portraits by Marlene Dumas. (Avedon’s portraits of Baldwin and his family are also quite telling.)

This isn’t a show that a professional curator would have done, but it reaches into corners that need dusting. As a whole, it underscores why we need to keep Baldwin in our lives today, right now, so the physical humanity we prize most isn’t lost in the shuffle of either fame or place.

• God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, David Zwirner, 10 January–16 February