If Banu Cennetoğlu were to show her recent, moving-image archive in Istanbul, where she lives, she would risk incarceration. Its lengthy title—HOWBEIT · Guilty feet have got no rhythm · Keçiboynuzu · AS IS · MurMur · I measure every grief I meet · Taq u Raq · A piercing Comfort it affords · Stitch · Made in Fall · Yes. But. We had a golden heart. · One day soon I’m gonna tell the moon about the crying game—might be enough to test the patience of Turkish censors, but it befits the projection of 128 hours and 22 minutes of film, video, still and every other manner of visual recording that Cennetoğlu shot at home, at exhibitions, and in the streets of one city or another over the last 12 years.

The work’s contents are another matter, one that marries private and professional life to the free flow of information and the maintenance of historical memory, currently restricted or subject to erasure in Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey, and increasingly compromised by corporate interests in America. In New York, the work comes across as enlightening but also threatening, mainly to traditional notions of sculpture.

No one at the jam-packed opening of Cennetoğlu’s first solo exhibition in the US seemed displeased. “It’s definitely an expanded idea of sculpture,” said Polly Staple, the director of London’s Chisenhale Gallery, the adventurous non-profit that originally commissioned the piece. “It’s about carving space and time with images and objects.” No question that the work is monumental. And, though unedited or manipulated, it’s almost surprisingly absorbing. (It helps that the sling chairs provided for viewing aren’t all that easy to get out of.)

In fact, the continuous stream of chronological but disconnected imagery—the birth of the artist’s daughter, an inebriated dance party at Kunsthalle Basel, the death of a child at a street demonstration, labor camps in Dubai—becomes as enveloping and contradictory as life itself, as well as, at times, as piercing or poignant. Because it consists of imagery compiled over a receding decade, the work also amounts to an informal history of digital media, from floppy disk to thumb drive.

For Sohrab Mohebbi, SculptureCenter’s new curator, the work represents a career retrospective for this widely respected artist and human rights activist, who must have been born with an archival gene. “We go through all of her exhibitions,” he said of the projection, “but also the research and production phase of the works, in addition to their social history. I have never seen so tight a weave of irony and sentimentalism,” he reflected, and compared the experience to witnessing an avalanche.

Though HOWEBEIT gives a subjective account of the artist’s life, it’s less about her than the time we live in, in equal parts disorienting, aching, aspirational and confounding. Visitors on any given day will see a different, six-hour selection, one of 22 parts and 46,685 digital files, but who’s counting? “I’d like to come back and back,” enthused the dealer Janice Guy.

Another, more object-oriented, element of the show is a kind of library, though not one composed of limestone tablets that Cennetoğlu inscribed with entries from the diary of a murdered Kurdish journalist and showed in Athens for the last Documenta. At SculptureCenter, she presents bound volumes of daily newspapers printed in several language and collected to show how different countries, or regimes, emphasise or withhold news of events or people—something one doesn’t notice when reading online, where editorial decisions regarding placement aren’t so visible.

Cennetoğlu, of course, is the artist who compiled The List, documenting the deaths of migrants and refugees since 2006. (It was vandalised numerous times during the last year’s Liverpool Biennial.) Borders in her own life are as porous as the frames of HOWBEIT. She carries a Canadian passport, lived in New York in the 1990s, when she worked as a fashion photographer, went to art school in Amsterdam.

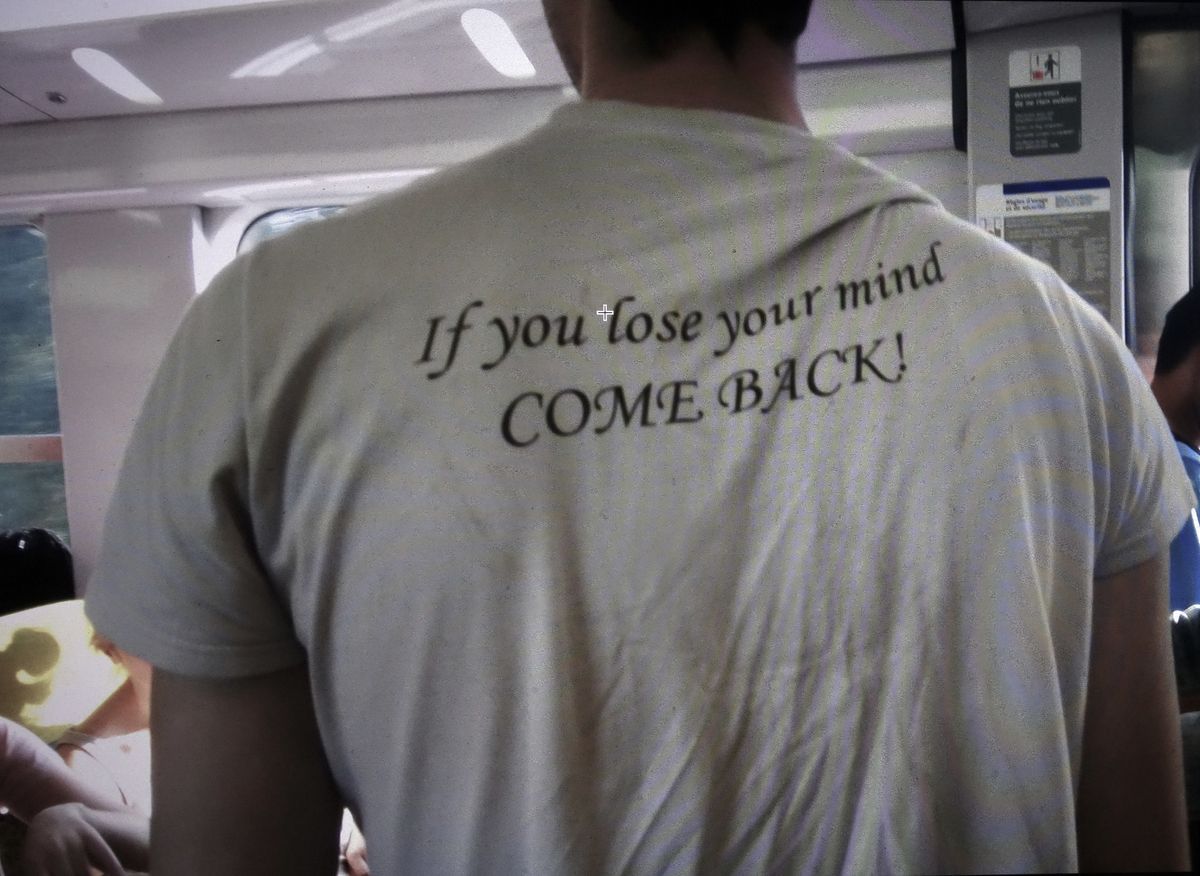

Introduced by Jill Magid, her former classmate at the Rijksakademie, I found Cennetoğlu to be an engaging, thoroughly committed citizen-artist determined to resist the forces of repression and bigotry in every way possible. The situation in Istanbul now is terrible, she said. People can be arrested for wearing the wrong clothes. Artists and writers have been detained without charges. She has to be careful, but she refuses to submit. Noting the Holocaust and genocides in Armenia and Rwanda, she said: “I don’t want to be one of those parents whose children learn of these things and ask why? To be silent is to be complicit. And I will not be that.”

• Banu Cennetoğlu, until 25 March at SculptureCenter