From a distance, the Lahore-born, Dallas-based Ambreen Butt’s paintings, inspired by Indian and Persian miniatures, display tantalising colours and intricate detail. A closer inspection reveals that the artist is addressing sobering subjects, from child victims of US drone strikes to the Pakistani government’s violent responses to women protestors, to the trial of a Bostonian jailed for abetting terrorists.

In a 2016 talk at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Butt spoke of reconciling art—beautiful and boundaryless—and the “real world”, which contains ugliness. “Whenever I see a lot of injustices and oppression and inequalities, it keeps showing up in my work,” she said. Her powerful works are on now display in the exhibition Mark My Words at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC (among the museums still open in the city during the government shutdown). In an interview, Butt expressed deep respect for the museums and its unique mission to support women artists. Exhibiting in the nation’s capital also allows her to “reach a wider audience beyond the art world,” she says.

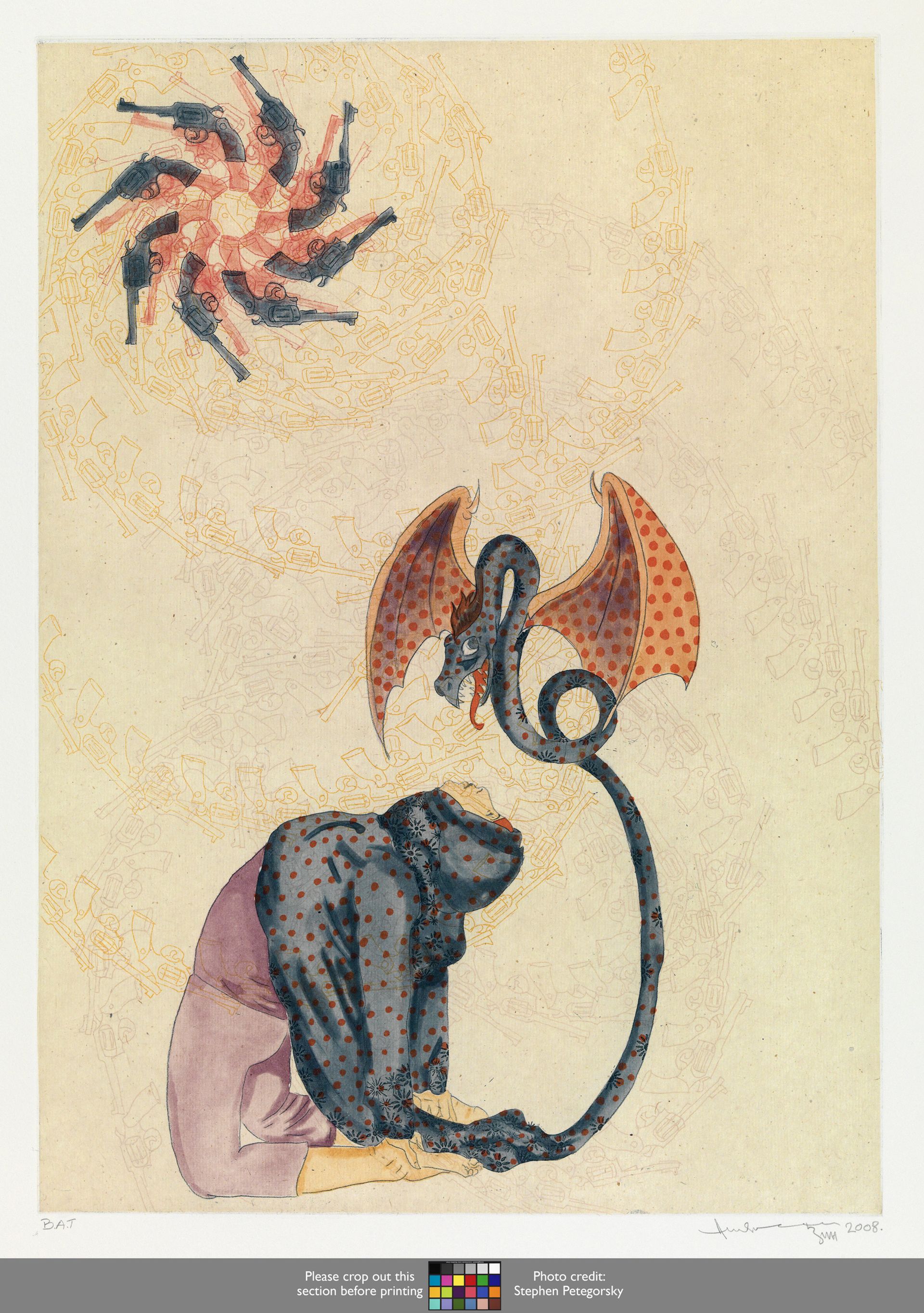

Ambreen Butt, Untitled (Woman/Dragon) (2008), from the series Daughters of the East, etching, aquatint, spit-bite aquatint, drypoint, and hand colouring on paper © Ambreen Butt. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Stephen Petegorsky

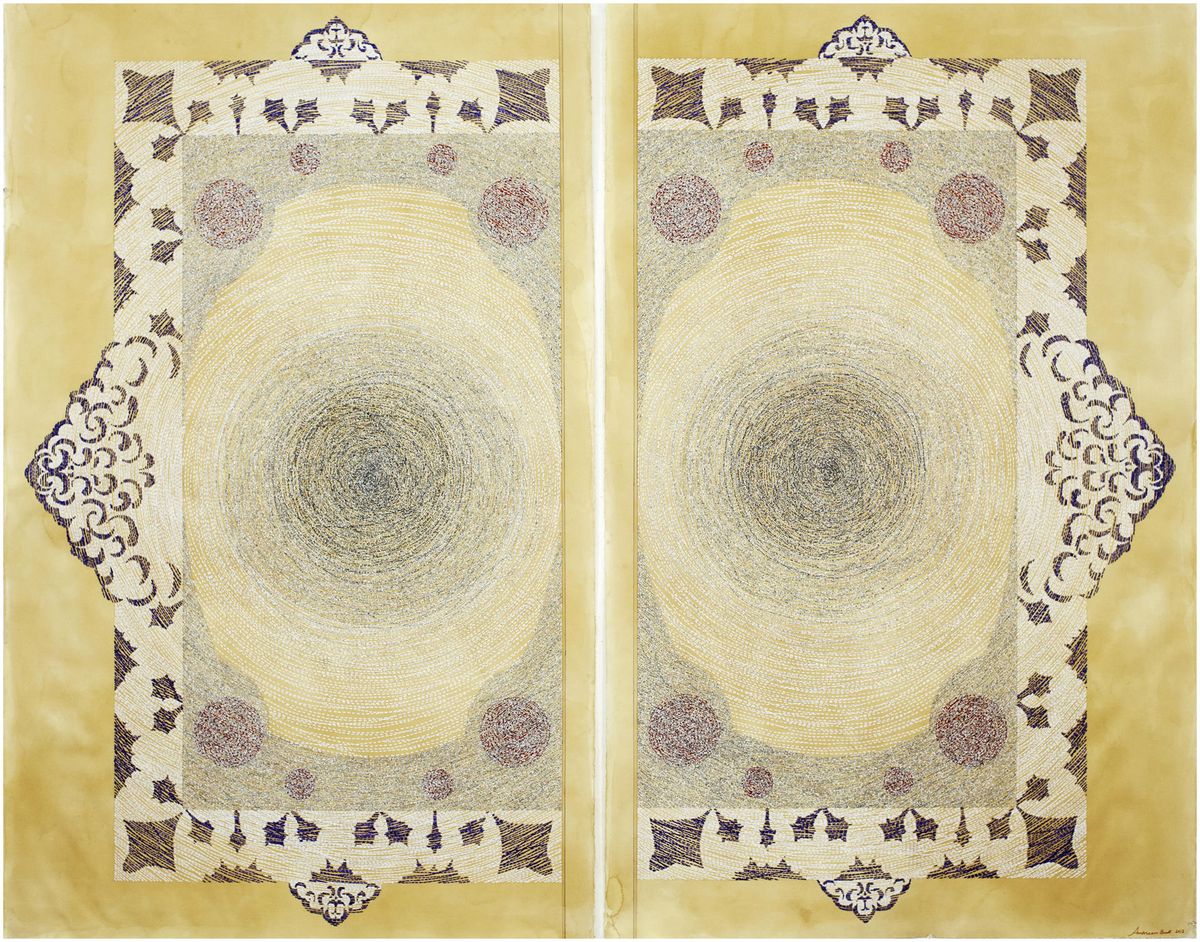

In several of the works in the show, Butt depicts strong yet vulnerable heroines and the Say My Name series memorialises Pakistani and Afghani children killed by US drone strikes. In the nearly six-foot-tall diptych Pages of Deception, she explores the arguments of both prosecutors and the defense in the case of Tarek Mehanna, a Boston pharmacist convicted of aiding Al-Qaeda terrorists. Butt tore up those legal documents and spent a year collaging them together in a piece that resembles an open, two-page sacred Islamic manuscript. “The text is present, but the meaning is missing for the reader, who cannot understand the language,” Butt says. “Though the piece is conceptually very political, I extract the aesthetics from the visual tradition I am most familiar with.”

Other common motifs in the show are mosquitos, ladybugs, dragons, and tigers, which play symbolic and complicated roles. Butt often builds up multiple transparent mylar layers, creating deconstructed miniature paintings where ghostly figures derive from medieval history and current events. The artist, who trained in miniature painting at Lahore’s National College of Arts, also puts her own spin on her multimedia works by sewing, etching, and gluing them.

“The techniques of traditional miniature paintings are taught through a strict curriculum of copying past masters, and even sometimes involve learning techniques like making one’s own squirrel hair paint brushes,” says Rachel Seligman, the assistant director for curatorial affairs at Skidmore College’s Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery who organised its 2015 show of 15th to 19th century Indian painting Realms of Earth and Sky. “In addition to expanding and modifying, some contemporary artists are also challenging [and] disrupting the tradition in various ways.”

Other common motifs in the show are mosquitos, ladybugs, dragons, and tigers, which play symbolic and complicated roles © Ambreen Butt

Miniatures are often small, but their name derives from the Latin minium, the red lead vermilion highlighting important words in European manuscripts. Arabs, Persians, and South Asians called their art taswir or tasveer in Persian, Urdu, and Hindi, meaning “picture”, but Europeans denigrated the works, which they saw as inferior to their own, Seligman says.

“Even people critical of this history of the term continue to use it, in part to draw attention to the remarkable skill that went into producing these paintings,” Seligman adds. “Educating Western audiences about the history and traditions and iconography of these works is extremely important in helping expand cross-cultural understanding and awareness of the ways in which our traditions, values, and beliefs have enormous common ground.”

Orin Zahra, an assistant curator at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, said that Butt draws on the the distinct character and technique of miniatures to “lure viewers to look more closely, to engage with her subject matter more intimately and directly.”

The artist’s focuses on freedom from oppression and empowering the disenfranchised are timeless, according to Zahra, but they are also particularly apropos. “Butt’s poignant and pointed critiques about societal corruption, unchecked and unrestrained power, and its resulting political violence are certainly relevant and significant in the present climate,” Zahra says.